June 2nd – July 30th, 2016 / Paris

Press visit with the artists on Thursday June 2nd / 2 – 4 pm

Almine Rech Gallery is pleased to announce the third solo exhibition of Ida Tursic and Wilfried Mille at the gallery.

Three times Bettie. This is what viewers first encounter at Ida Tursic & Wilfried Mille’s exhibition at Almine Rech gallery in Paris. Three times Bettie Page, the memorable pin-up girl. She was famous in the Fifties, but also well-known for the numerous fetish photographs representing her. Three times Bettie Page, meaning three identical paintings which, spaced apart, finally take over in its entirety the very large wall facing the entrance of the exhibition space.

We imagine these three are identical –except for a few details, as the artists made the decision to vary the content of a small frame hanging on the background wall inside the paintings– before each receiving a different pictorial treatment, diverging not in its nature but in its consequences. This pictorial treatment is three times identical in nature then, with colored, architecturally laid-out spots applied on the surface once the portrait underneath is finished. Its consequences fluctuate according to which part of the body or the décor are covered with paint smudges, inflicting an obvious singularity to each painting by radically altering its composition.

Thus maculated with paint, these three Bettie Pages are facing us without looking at us. The gaze of the “model” is directed downward, but what imposes itself is its posture and more specifically the position of the legs, which sends us some clues to cling to when cognitively scaling the picture. The legs’ position is the same as in Manet’s Fife Player, (1966), or the central figure in Georges Seurat’s Models, (1886) a painting which also contains three characters. Three times the same character, standing up, legs apart, as in Andy Warhol’s Triple Elvis, (1963). Three times the same figure –it is actually not that common. With Ida Tursic & Wilfried Mille’s paintings, it is recurrent; as if a spluttering of information ran across them, leading the mind inside a flow of more or less clear-cut pictorial memories, something far from incidental. Tursic & Mille’s art is of the kind that wants to confront history, the history of painting, which is, of course, Manet and Seurat notwithstanding, mainly from the 20th century, from Pablo Picasso to Christopher Wool. It may seem insanely ambitious but if you go to the bottom of it, it is the only way to go. This is the great singularity of Tursic & Mille’s painting: it doesn’t resort to the cynical view that pretends history is over as an excuse to adopt a cavalier attitude. Their painting seems to feed off other kinds that precede it, not all of them, thankfully, but the ones that, precisely, also confronted history. In short, their paintings want to battle this history, or at any rate dialogue with it, or even, more accurately, invite a dialogue with it.

They evidently ogle history then, but their field of vision expands toward the present, where their focal point in fact resides. At a lecture the artists gave at the Collège de France1 in Paris on October 31, 2014, they most notably said that they “were establishing an enormous database with roughly 140,000 images as of today, filed more or less haphazardly (with categories as diverse as “dogs, news, NASA, spankings, flowers, Marilyn Monroe…”). No need to go down to the market anymore and look for a suitable apple to paint, we’ll type “apple” in Google search and we’ll get 2,310,000 results.”

In fact, the original image for the three Bettie Pages comes from this database constituted of tidbits extracted from the internet, as does the one for the languid female figure in the bottom part of another artwork in the Parisian exhibition, whose position clearly evokes the character in Marcel Duchamp’s Etant Donnés : 1º La chute d’eau 2º Le gaz d’éclairage (1946-1966). Fundamentally, what happens is our mind goes to fetch Duchamp, Manet, Cézanne, this or that painter, but nothing from their work is actually present in Tursic & Mille’s canvases. In the end, what we see are simply images carrying inside of themselves something that triggers these memories. This is the other gamble of Tursic & Mille’s painting: finding the vehicle conducive to this dialogue with history within the incoherent jumble of images on the internet, with their specificities, imperfections, occasional compression mishaps, their diversity, too, their sheer number even.

These images evoke poses but also genres that are traditional within the history of painting. The pornographic images the artists were using at the beginning of their career offered a contemporary perspective on nude painting, while flowers and fires did the same for landscape painting. Very quickly it becomes obvious that these images are anything but a pretext (and, in this case, very literally, what comes before the text), and that their subject isn’t a specific image but Painting itself. “How can a painted image talk about anything other than just itself?” they asked at the Collège de France.

In some of their older artworks images were printed on canvas thanks to a kind of thermal ink, but with this exhibition they are all hand-painted, as if the process of transforming them into painting started as soon as they are inscribed on the canvas. This is because what is in question is a confrontation between painting and contemporary images, and in this matchup each party is girding itself for battle, sharpening weapons, honing them. Sometimes the image holds up well, at other times it gets defeated: in Watch4Beauty (the title refers to the online erotic site from where the image was borrowed), paint seems to have triumphed over the painted picture –of a pin-up girl– covering it almost entirely, fabricating in essence its own pictorial composition. The painted image is not defeated by the additional treatment it received in a second phase (two stages are clearly visible –the reproduction of images, followed by their covering); rather, the painting begins with an image that is manually reproduced, then continues with its obliteration. It is this obliteration that finally bestows the painting with its own identity.

As far as identity is concerned, Tursic & Mille are often asked about the unknown mechanisms at work within one painting made by two collaborating artists: people would like to know who does what, how things go in the studio. It is true there are very few references in art history to compare them to. Indisputably, one of them does this while the other does that in the same way that their paintings are both a painted image and its own obliteration. Similarly, it is the combination of the two authors or of the two stages in their paintings that fashions this singularity whose elements make no sense without each other.

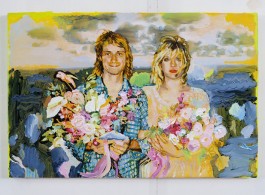

In an adjacent room, an impressive series of small paintings on wood is hung in a profusion that is more natural for images found on the internet than for painting. They seem to have been assembled together by a kind of loose logic similar to the one that decides on shared commonalities for this or that image via the use of a few hashtags. Their humble format is not so different from “Google Image search results” –the simplified stage, advertisement-like, which precedes the future image to come. There are famous painters, and artists that are similarly famous (Edouard Manet, Piet Mondrian, Gustave Courbet, Paul Cézanne, Jeff Koons, Jean-Dominique Ingres, Martin Kippenberger, Marcel Duchamp, Pablo Picasso, David Hockney, etc.), artists from other disciplines who are as worthy of admiration (The Sex Pistols, Kurt Cobain, Michel Houellebecq, Iggy Pop, Marguerite Duras, Jean-Luc Godard, Lindsay Lohan, William Burroughs, Oscar Wilde, Marilyn Monroe, Ian Curtis, Honoré de Balzac) –there are a few friends also, even a dog. Painted on wood, there is little doubt about them being icons. There is no doubt either they form a personal Pantheon. One of these little paintings on wood, representing Liz Taylor indulging in a spot of amateur painting in front of an easel, against a mountainous backdrop with outrageous hues (“Elizabeth Taylor in a landscape, painting nature’s beauty and the caress of the smirking sun over the mountains,” 2016) lends its title to the whole exhibition, according to a principle borrowed from music records, where the title of a song that is not necessarily the hit single is also given to the album, maybe because it synthesizes its spirit better than the hit song itself. Thus, it will be this little picture representing Liz Taylor that will be necessary to look at, and look at again, to access the spirit of this exhibition.

Ida Tursic & Wilfried Mille’s painting is resolutely complex; this complexity the precondition of its very existence (with its sources and their interweaving, its execution and variations), which naturally differentiates their painting from “images.” Their canvases are where this ambition, exposed to our gaze and showing the various stages of an incessant experimentation that is both conceptual and handmade, is sedimented and crystallized. An attentive observer will easily discern what distinguishes these works from those gathered at their previous exhibition at Almine Rech Gallery in Paris in 20102. Ida Tursic & Wilfried Mille’s style is immediately recognizable at first glance, but the strategies and techniques underlying its permanence undergo some significant variations, never stabilizing themselves inside the comfort of a one-size-fits-all solution. As the artists explain with ease, “each picture redefines the way we conceive painting.”

Eric Troncy

1 “The Manufacture of Painting,” Collège de France, October 30-31, 2014.

2 “Come In Number 51” Almine Rech Gallery, Paris, September 11-October 23, 2010.