For three years until a while ago, I sat in an office building at Hong Kong’s Tsim Sha Tsui for most of the working week. When I met David Diao, he told the story of the apartment in a low-rise building on Chatham Road where he lived in as a child when he arrived in Hong Kong from Sichuan, Mainland China. This would be his address for five years before he moved to the United States in 1955. By coincidence, Diao’s former home, now replaced by Best Western Plus Hotel, was the view across from the office window. The hotel there is no longer a fixed ‘home’ to anyone, but instead a series of rooms for transitory visitors.

Maybe it is not surprising that the work of David Diao features plans, interiors, exteriors, rooms and houses. In the announcement for his 1970 exhibition at 470 Parker Street Boston, an image of a workman, who bears some resemblance to Diao, is seen plastering a wall. The exhibition featured works made using building materials like plaster and sheetrock, putting forward Diao’s now established norm of making paintings with tools instead of brushes.

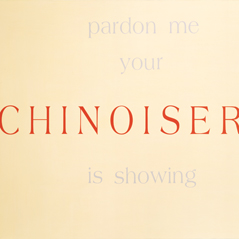

Diao’s art career in the 1970s made him a formidable American Modernist, capturing the era while showing few hints of his Chinese heritage. Every now and then, under the usually matter-of-fact titles would be suspiciously loaded references, with works like “Odd Man Out” (1974), “Made in USA” (1979) or “Wealth of Nations” (1972). Knowing Diao, I am certain that that he has a story behind each title; he is just not necessarily letting us in on it. The artist, who was perhaps initially seen as a Greenbergian formalist painter, turned the corner when the 1980s arrived. Armed with some freshly found, wickedly sardonic wit, he would reappear in the mid-1980s as a disciple of art who had lost faith in the Modernist legacy.

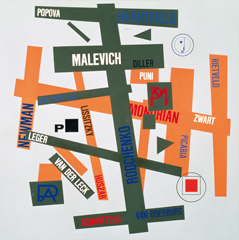

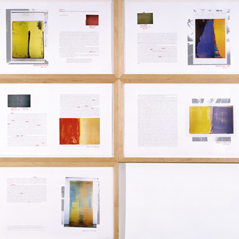

If we cast our eyes back over the past four decades, few artists with long careers like Diao carry the same verve or on-going transformative impulses in their work. By the 1990s, Diao’s inventory would undergo a radical redesign. First came the artist Barnett Newman’s series of abstracted resumes and chronologies, followed by pointed, unyielding works like “The Bitter Tea of General Yen and The Board of Trustees…” (both 1994). Later on in 2005, there was the “Demolition/At Risk” collection where the artist mused over the cemetery plots of dead artists and beautiful, though dilapidated, Modernist buildings ravaged by time and nature.

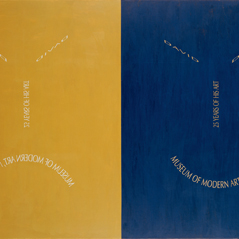

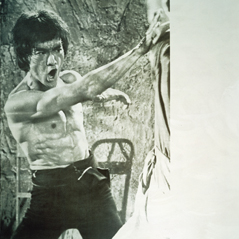

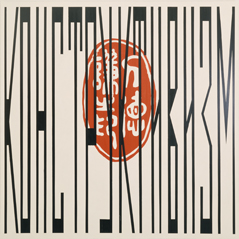

Diao’s radical and suicidal art world approaches surfaced in works like “Slanted MoMA” (1995) a nearly 2 metre long painting where a diptych of happy and sad faces announced “25 Years of His Art”. A year before, another invitation for a fictive retrospective at the Pompidou Centre appeared on another painting “Carton D’Invitation” (1994), flanked by the famed Bruce Lee in a full-force martial arts mode. In the 1990s, Bruce Lee, the martial arts legend, self-styled philosopher, celebrity actor, Kato of television’s The Green Hornet, served as a superlative surrogate for Diao. With more than a large dose of self-mockery, Lee was a flawless vehicle, acting as a stand-in for Diao’s wry artist declarations.

In Michael Corris’ essay for the publication David Diao: Works 1969-2005, he stated “those who know Diao best would balk at the notion that the artist’s Chinese ancestry was in any way responsible for the trajectory of his career. For them, it was simply invisible.” As a migrant to the United States in the mid-1950s, one could see Diao’s subsequent education had been fully nurtured by a supposedly ‘seamless’ integration into broader American culture. In short, by today’s ideological standpoints, Diao would have been the ‘perfect’ assimilated Asian-American’ artist, ticking all the boxes on the American cultural agendas. Except that perhaps the category didn’t exist in the American art scene then, or elsewhere today.

So Diao remains an art enigma, an insider-outsider, accepted by the art institutional system though often over-looked. The principle of inclusion and exclusion in the cultural game is perhaps ultimately as much about authenticity as it is about how one looks the part one might be playing. Most certainly, Diao’s gamble of exercising his brand of biting satire on these institutions through his paintings is dicey to say the least.

Since the 1990s, Diao has been at times flippant, and at others morbidly grave, jesting at himself and the art world. The artist’s works are cool, but rarely frosty, and they always carry a sense of humility and self-deprecating humor. The invisibility of Diao’s ethnicity is, upon closer inspection, more a matter of shielding. I want to suggest that the titles of the Bruce Lee paintings like “Reading” (1999), “Reading and Waiting” (2000) and “Waiting” (2000) all imply that Diao was in a state of observing and perhaps deferring his own identity and place in the art world. In “Hiding” (2000), Bruce Lee’s face was obscured by a 1970s Smiley Face in an uncharacteristic metallic gold tone. This is a strange picture and composition. But like some of Diao’s most interesting pieces, it is not necessarily the most aesthetic in a conventional sense. The unexpected visual intrusion of the ‘happy grin’ is at the same time assuring and hostile, as if masking an imminent threat from the Kung Fu master from beyond the grave.

By the late 1990s, Diao also began inserting himself directly into works like “Lying” (2000), “Dancing” (2000), and “Sitting in the Glass House” (2003). In the two former paintings and their variations, Diao lounged intently in front of works by Jackson Pollock and Henri Matisse. In “Sitting in the Glass House”, he made himself at home in a Philip Johnston house, framed in a Josef Albers’ style geometric field. It is a touching and distressing act, as if the artist made a valiant attempt in inserting himself into a larger picture of art history that may not belong to him. Through these works, Diao initiated a conversation about race and representation, as much as his place in the scheme of things.

So far, Diao has proven to be many things: Modernist, Postmodernist, art radical, art jester, art world ‘suicidal’ artist…In 2008, some forty decades after he began his career, Diao presented the series Da Hen Li House in Beijing as a kind of homecoming, and yet another uncharacteristic twist in his repertoire.

Diao’s Da Hen Li House is deceptive in its mirage. One the one hand, the artist inadvertently plays into the act of re-introducing himself to the art world as a ‘Chinese’ artist. Gone are the nudge-nudge, wink-winks about the art world, the rejected art sales, or the conjured-up museum retrospectives. On the surface, the series served as an evocative remembrance of times past, re-imaged documents of memories that were bitter and tart. For viewers who were familiar with Diao’s previous output, the works from Da Hen Li House were an anomaly, a break from the artist’s critical and occasionally sardonic voice on the art system. Or reading against the grain, the show could even be seen as the artist’s desire to be included in the larger domain of ‘Chinese’ art, of which he is also rightly a part.

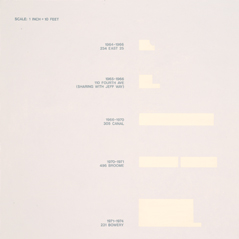

In Da Hen Li House, Diao’s emblematic paintings served as re-imagined ‘evidences’ of lost memories that the artist retrieved with the assistance of his family. Each painting in Diao’s series also takes on individual ‘rooms,’ as if in a timeline structure as the narrative unfolded. We witnessed a pair of tennis balls, the gingko leaves (a green background for the summer, earthy tones for the fall); “Not to Scale”, a stylized map of China, Hong Kong and Manhattan. A painting that spells “One Suitcase Per Person”, the plan of a tennis court, “The Good Earth Google”, an online satellite view of the house’ former location, and lastly “Return to Sender”, a work made up of a grid of envelopes with the return address “Diao Residence, Da Hen Li, Hua Xing Dong Jie”, evidence that the house actually existed in time.

Intriguingly, in all of Diao’s works from the past containing houses and architecture, such as “Spoor-Tugendhat House” (2004), “Window” (2004), “Four Seasons” (1999), “Figure/Ground” (2005), or “Melnikov Studio” (2012), we are able to see, in actuality, the buildings’ elevations or their interiors. In Da Hen Li House, Chinese Communism and its subsequent cultural eradication offered us no such luck. Despite the fact that we knew that house is large enough to house the offices of the Sichuan Daily and has the tennis court that played such an important and integral part of the Diao’s narrative, the building remains in an illusory, broken past where all that is left are traces of the foundations.

The fact that Diao did not actually recreate Da Hen Li House’s now long disappeared architecture points to the fact hat he seems well aware that these material spaces are perhaps nagging ghosts that no document or history can possibly contain. Diao’s journey has travelled through many houses, studios (his and that of other artists) and more recently very personal, “un-entered’ rooms.

Hot, Bitter, Spiced and Chilled

At David Diao’s retrospective that took place at UCCA, Beijing in October 2015, a young student, prompted by her art teacher-in-waiting, asked Diao what his favorite ice-cream flavour might be. The question, which arrived at the end of the artist’s forum, probably came out of frustration in trying to affix Diao’s works into a larger scheme. Neither entirely hermetic nor overtly political, formalist nor expressionist, Diao is slippery, yet earnest, even as he professes “I don’t wear my heart on my sleeve.” At breakfast the following morning, it came to him: “I should have said ‘Hot and spicy’ as I am from Sichuan. Also I hate bitterness and some would have me liking vinegar.”

At 72 years of age, most artists are happy to spin on their established styles. Diao’s refusal of the formulaic is apparent. Da Hen Li House led him on a journey that took the artist from his number 72 Franklin Street studio back to number 73 Chatham Road in Hong Kong, his home between Chengdu and New York when he was six. The devastating voyage in 1949 split Diao’s family, leaving his mother and sister behind, not to meet again until some three decades later.

Perched in her downstairs apartment was Li lihua, the actress who was gloriously hailed as “the first beauty in China” and a favourite with audiences. In “She Was a Neighbor” (2014), a double portrait of Diao and Li appears over a map of Hong Kong and the Kowloon peninsula. This is a young Diao dressed in a cowboy tee shirt while Li was styled in a Calamity Jane- cowgirl attire for the cover of The Rambler magazine. With a railway track in the centre, protruding beyond the painting and cutting the composition into mirroring halves, Diao’s visually obscure, yet literal representation of a highly personal moment is extended and brought forward to a broader arena with the Chinese title of the magazine: “Free(dom) Speak.”

In the 2016 version of the Li Lihua work “Neighbour” (1950-55), Li’s portrait for a 1953 magazine named Hong Kong further cements the oeuvre of Diao as an archivist of the artist’s past (1), Diao’s Five Years in Hong Kong series (2), with a plethora of maps, itineraries, school crest and signboards all trickled down into a kind of impossible remembering of what had gone before.

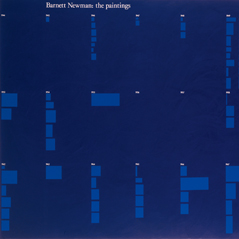

Even a work such as “Spine 2″ (2012), an elegant silk-screened painting of a 1960 Barnett Newman catalogue cover for Newman’s Station of the Cross series gains an alternative interpretation. The cracked spine with its myriad of tiny creases flows through the length of the work like a river, diverted into small streams as they dissipate into the purple ground. Diao may seem to be nostalgic and sentimental in his recent offerings, but his humour persists, referencing himself as “spineless” in relation to his long obsession with Newman, his appropriation and the art world at large.

In the light of Diao’s impossible project where the markers of Diao’s American and Chinese identities turned indeterminable and unfixed, Da Hen Li House provides a threshold for Diao; in fact we are now provided a platform where his other projects may subsequently accrue new interpretations because of it. With Diao’s uncharted voyage between Chengdu, Hong Kong and New York continuing, one may recall the old Bacharach and David song A House is Not a Home. Balladeering aside and no matter how transient or imagined these ‘houses’ may be, they are, without doubt, residues of his ‘shelters’ in an on-going itinerary.

Notes

(1) Li, on learning she was the subject of Diao’s work, had her assistant visiting Diao in 2015.

(2) Works from the series were exhibited at Art Basel Hong Kong 2016.

With thanks to Norman Ford and David Diao.