“Rina Banerjee: Migration’s Breath”

Ota Fine Arts (7 Lock Road, #02-13 Gillman Barracks, Singapore) Jan 23 – Mar 21 2015

“Rina Bannerjee: Human Traffic”

Nathalie Obadia (18 rue de Bourg-Tibourg, Paris) Sep 12 – Oct 24 2015

Look at these sculptures as sculptures, the paintings as paintings. Try, if you can, not to look at them as ethnographic specimens, multicultural whimsy or feminine autobiography. You shouldn’t, anyway. Which is to say, looking should not involve gazing through a palimpsest of clichés. It should not involve prejudice—at least, we should be more self-conscious of our inadequacies as viewers.

Born in Calcutta to a Hindu Brahmin family, Banerjee’s work is informed by her home—which is not exotic but merely (one) home (she also grew up in London and New York, where she still resides). Importantly, her work is also informed by memories of visiting her grandfather during his homeopathic treatments.Even this, however, is only one aspect of her work. Banerjee is also a trained industrial chemist and studied painting at Yale.

Such exegesis seems excessive, but the narrative of a female artist drawing on her “ethnic” roots for inspiration is rather too easy; it appears frequently in articles about Banerjee, however well-intentioned they might be.

So stop, and look.

The sculptures are colorful and textured constructions in the vein of Isa Genzken, involving diverse materials—feathers, beads, shells, horns, ropes, light bulbs, wire mesh, and dried branches. Occasionally the sculptures are freestanding, but usually they hang from walls, invading personal space, feathers moving, wire branches swaying, as someone walks by. Scale is crucial, too. They are not huge, but human. They fit into the spaces we inhabit rather than visit—homes and offices and their corridors rather than cavernous halls. These sculptures are made to be experienced in the space of the everyday, the spaces in which life mostly happens. Some look like mad hats, some like gods, some like strange laboratory experiments. But think of them too—think of them first—as constructions of color and form in space—not neat and tidy, not self-important, but transmogrifications of ideas into forms and back again, witty and horrific meldings of formal and conceptual arguments. Sex, religion, cultures and histories are all formal matter, all media for assemblages that disturb and charm, but reveal themselves slowly. Certain elements carry specific associations, such as the light bulbs—electrical receptacles, illuminating eyes and idea breeders, with metaphorical dualities both physical and sexual.

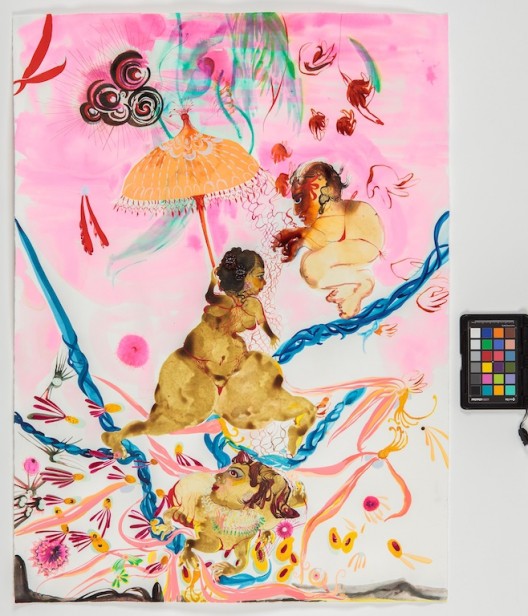

The paintings, seemingly more traditional in guise, are also about how space is covered—scale, line, color, texture (the watercolors are not a secondary medium—their medium is part of their biological, cultural and political message). The figures, overwhelmingly female (avatars of the artist, not self-portraits), run riot with the scale, overwhelming their two-dimensional worlds and three-dimensional frames. Stories are being told, but in a way that makes your eyes work, moving about the picture plane, following this line, this shift of color. Note the high-heels and fairy godmothers, thongs and dresses, but also the swirling waters and clouds of color, and the way everything floats in space.

Recent discussions of so-called zombie abstraction have largely ignored one of its more curious, if not unexpected characteristics: it is overwhelmingly male. Yet, in this age, many of the most interesting artists working in relation to abstraction—even if they do not define themselves as abstract artists—are women. Obvious examples are Sue Williams, Katharina Grosse, Tomma Abts and Beatrice Milhaze, but one can just as easily include Wengeche Mutu, or in China, if less well known, Liang Wei. Abstraction and non-representational art are not the same thing. All representational art involves abstraction. And non-representational art is very likely an oxymoron. Looking at and experiencing Rina Banerjee’s sculptures and paintings, it is crucial to remember that the art lies not only in the cultural, political and sexual layers of the works, but in their artistic chemistry and physics: a collection of physical elements arranged in space and time for the eyes of people.

Rina Banerjee, “In abstinence, in resistance like vegetarianism viewing truth to replace food, re- place shame, the indecen- cy of craving to belt desire she turned loose grew to tire and skip to her circus hour dangled on tight rope of blue wire so she was inspired”, acrylic on watercolor, paper arches, 76.2 x 55.9 cm, 2014. (© Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Bruxelles).

Rina Banerjee, “Make me a summary of the world, she was his guide and had travelled on camel, rhino, elephant and kan-garoo, dedicated to dried plants, glass houses – for medical study, vegetable sexuality, self-pollination, fertilization her reach pierced the woods country by country”, pedestal wooden with 2 umbrellas, six plastic horns and grape vine, shell and ceramic doll, wooden Rhino 243.9 x 106.7 cm, 2014. (© Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Bruxelles).

“Rina Banerjee: Human Traffic”, exhibition view at Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris (© Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Bruxelles).