This fall, Shanghai’s profusion of events made it almost seem like the central hub of contemporary art in China. There was the battle royale of art fairs in September (Photo Shanghai, SHContemporary, WestBund—not to mention the artist-run fair, Positive Space), the arrival of new galleries (MadeIN Gallery; Arario, the Korean gallery that left Beijing and now resurfaced in Shanghai; Matthew Liu Fine Arts; and two locations for Mao Space), and the second edition of Art021 last week. The cascading wave of shows and activities in Shanghai surely crested last weekend, with the opening of the Shanghai Biennale and (yet) another new museum, the Shanghai 21st Century Minsheng Art Museum (M21), along with a number of lectures, seminars and performances which all happened to happen at once. Here is an overview of what happened—with more coverage to come later.

On Wednesday (Nov. 19), as a prelude, Biljana Ciric’s “Just as money is the paper, the gallery is the room” opened in Osage Shanghai’s relatively obscure space (art-wise). Though one art-worlder later quipped: “I only ever pass by when heading to Qiao Zhibing’s art restaurant,” the opening was well-attended, surely attracted by Osage’s new found vigor but also by the curator’s reputation. The exhibition groups together a diverse range of artists, and focuses rather strongly on reflexive curatorial approaches and exhibition histories. The British/Polish artist Marysia Lewandowska’s work, “Shanghai. Exhibition Histories Distributed”, for example, reexamines the historic sites of exhibitions in present-day Shanghai, complete with photos, a map and replication of a particular tile pattern in a Shanghai art college. There were some usual suspects from the Chinese art scene (from “elder statesmen” such as Yu Youhan, Ding Yi, Zhang Jian-jun and so forth, to younger artists like Hu Yun and Li Ran), all of whom contributed works that reflected on exhibition history in some form or another. This was combined with the works of foreign artists such as Yason Banal, from the Phillippines, who presented digital works (“Dangerous Grounds”) as well as the Yugoslav art collective IRWIN, with their invention of an embassy of a fictional country in Moscow (and now with a similar proposal in Beijing)—slyly taking on political symbolism while hinting at the vagaries of changing state borders in Eastern Europe (“Revisiting Project Proposal for NSK Embassy in Beijing”).

On Friday (Nov 21), the key highlight was the opening of the Shanghai 21st Century Minsheng Art Museum (M21), yet another museum to open in Shanghai, this time in the former Expo grounds in Pudong—the former French pavilion, to be precise. Clad in a latticework of a curtain wall, the museum’s main hall spirals upwards in a rectangular form (in contrast to the circular spiral in New York’s Guggenheim). Unlike the Guggenheim, the central section is a large white cube and thus blocked off from view, creating either a claustrophobic or else a tunneling effect.

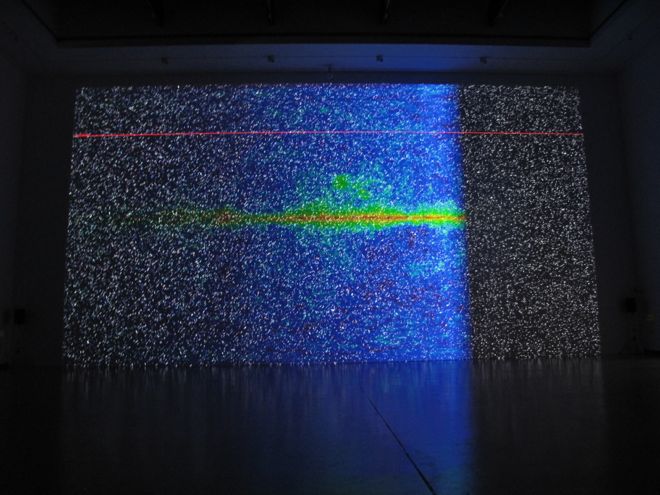

The curatorial theme, “Cosmos” (or “Duochong Yuzhou”, which literally means “multiple universes”) seemed to have been chosen to be loose enough to take in as many kinds of works as possible—in other words, a theme tied together with very loose filaments. Ryoji Ikeda’s “the radar [shanghai]” was a razzle-dazzle light show of constellations on an enormous screen (1170 x 2200 cm) within an even more enormous white cube. A work which momentarily reminds us of the notion that contemporary art often seeks to evoke a sense of wonder through sheer scale (especially as the sense of wonder is being lost as the world shrinks through interconnectivity)—though on the other hand, sheer scale seems to make up for everything else in China—as much in contemporary art as in the era of ancient megalomaniac emperors.

A few highlights out of the mostly competent if not terribly exciting works: Song Dong’s “A Pot of Boiling Water” was presented in photographs—and then lo and behold, the artist emerged and performed the piece on site. Yang Zhenzhong’s “Please Sit” featured an installation that played with the slanted floors: the moment one sits on one sofa armchair, it rolls down gently before coming to a stop, moving back up through the help of a robotic motor contraption only when the sitter stands up. Continuing the artist’s exploration of mechanical devices (begun with massage chairs), the piece also imparts a subtly ominous sense of something not quite right—which perhaps also encapsulates the entire show.

Ryoji Ikeda, “the radar [shanghai]”, 1170 x 2200 cm, audiovisual site-specific work, 2014

池田亮司,《雷达(上海)》,1170 x 2200 cm, 音视频特定空间作品,2014

Yang Zhenzhong, “Please Sit”, site-specific installation, 70 x 200 cm, 2014

杨振中,《请坐》,特定空间装置,70 x 200 cm, 2014

That same night, the art world circuit moved on around town: to Aurora Museum in Lujiazui in Pudong, or to Arario (showing Gao Lei) on the complete opposite side of town; the ambitious did everything. Aurora Museum featured contemporary artworks within a museum of ancient and classical Chinese art—visiting the museum is a particularly pleasing experience given the attention to details like lighting, labeling, and display, not to mention the sheer caliber of the works themselves. It is often rather difficult to insert contemporary art within classical art pieces; whatever dialogue usually looks like a clash. With this show, the works mostly succeed, mainly by the curator Davide Quadrio’s choice of quieter works or by their judicious placement (for instance, Li Shurui’s piece along the windows, or Liu Jianhua’s white sheets in front of the Buddhist statues).

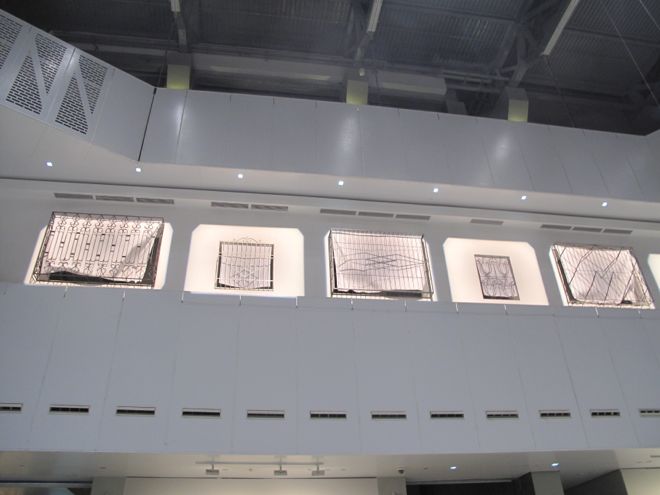

On Saturday, the main event was, of course, the opening of the Shanghai Biennale at the Power Station of Art (though Biljana Ciric also launched her book A History of Exhibitions: Shanghai: 1979-2006 in a discussion with Zhang Jian-jun and Shi Yong). Of course, a proper review of the biennale is called for, but what follows is the first impression. Certainly, it looked once again to be a last-minute miracle that works were almost all installed, with the slightly patchy installation and rough edges one often sees in China. There was a slight upward tick of German being spoken, with a slightly more international contingent than normal—no surprise given that Anselm Franke is the first foreigner to curate the Shanghai Biennale. One highlight was Liu Chuang’s “Windows”: the sense of memory was surely enhanced by the light projections. Less successful in terms of placement at least was “The Truth or: How to Teach the Piano Chinese” by Peter Ablinger and Winfried Ritsch, a piano and screen installation which sat very uncomfortably in the main atrium.

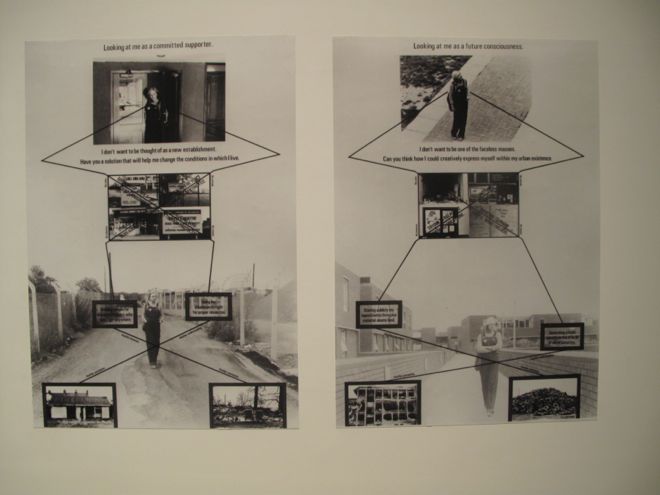

Given that the theme was “Social Factory”, there was a distinct focus on production and industry of all forms (sometimes very directly, as in Zhao Liang’s “Black Face, White Face”), as well as a harkening back to the 1920s–1940s, an early heyday of revolutionary agitation and politicized art in China. At first glance, some of the more historic works—woodblock prints—seem rather oddly placed. And many of the works really demand a deeper rereading, which exceeds the normal attention span of an opening. Hou Chun-Ming’s “Father” displayed thoughtful stories of fathers (unfortunately only in Chinese). “The News Blues” (by Nicholas Bussmann) was a delight: an a capella group which slowly sang through the texts of a newspaper—absurd, but beautiful. Yin-Ju Chen’s haunting “Liquidation Maps” charts astrological permutations of infamous massacres in history. There was, unusually, a music curator for this biennale—two performers played at the Xintianyou installation, in which an artist set off on a slow trek through northern Shaanxi; elsewhere, music was scarce to be heard (Yan Jun’s work was really more an aural assault on the senses).

Li Xiuqin, “Touch and Image—Give an Opportunity for Equality”, aluminum cast, 2013

李秀勤,《触像——给平等一次机会》,铸铝,2013

On Sunday, a whole slew of events continued with viewers looking markedly more haggard and/or hung over. Sean Scully’s large-scale exhibition opened in Himalayas Museum, Leo Xu Projects hosted Cui Jie’s solo show, with her architectural paintings, FQ Projects showed Wang Dawei, and Wang Yiquan wrapped up his “online residency” with Basement 6 (but not at Basement 6) with a performance. Across the Huangpu river in Pudong, the “Coming Soon—2014 Dong Chang Cinema Art Project” (curated by Su Bing, Lin Wei, Xu Jie) took place in an old cinema from 1954—which, after 10 years of disuse, faces demolition and reconstruction in the beginning of 2015. Both interiors and exteriors have kept that 80s style of décor in China, with “Coming Soon” blinking large and bright outside, while inside, a dozen or so old cinema seats were piled up high. At the opening, the artist Yang Ye, along with a group of students, wore masks that said “No talking today” and sat on a huge pile of art books and catalogues in front of the cinema entrance, prompting quite a few neighbors to wander what on earth was going on. Inside, several works and interviews with video artists were shown, with an intense sense of nostalgia permeating the entire cinema.

There were also talks, for those still who were compos mentis. Maria Lind, Nikita Cai, and Biljana Ciric talked about curatorial practice in their book launch (Active Withdrawals – Life and Death of Institutional Critique), while the Journal of Chinese Studies also launched, with Bao Dong, Fei Dawei, Zhao Qie, Robin Peckham, Pi Li, Lu Mingjun, Hu Bin, among others. As the first Chinese-language academic publication about contemporary Chinese art in China, the journal hopes to break down some of the barriers between art history, art criticism, and art theoretical writing, not to mention those between the various disciplines in the humanities; it also “strives to replace the historical narrative which has become a cliché”. Helmed by Lu Mingjun and published by the Central Compilation and Translation Press, the first volume will focus on “Shifts in Sensorial Mediums and Means of Cognition”. At the launch, Bao Dong stated:

“Contemporary art has become a cultural phenomenon and not just something within a small-circle sphere of art. We, too, hope to broaden the orientation of contemporary art.”

Yet, a total of 40 or 50 people were present in the audience, most of them art insiders, and media coverage is likely to be negligible.

On Monday, the winners of the International Awards for Art Criticism (IAAC). Su Wei won the first prize (50 000 RMB and a residency in London), while Joobin Bekhrad and Zhang Hanlu won the second prize. Read more about this in our report here.

And then on the seventh day, everyone rested.

(by randian, with contributions from Gu Ling)