From 4 November 2016 to 8 January 2017, the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) presents “Hao Liang: Eight Views of Xiaoxiang” in the Central Gallery. Hao Liang’s first institutional solo show, the exhibition showcases a new cycle of eight large (387 x 184 cm) compositions in ink on silk that take on this time-honored titular landscape in Central China, using each image to explore the dramatic sublime of the contemporary ecological landscape. His paintingis based on research into the literature, aesthetics, and scholarship of Chinese antiquity, seeking to revive a genre and its material artistry, and imbue it with a modern sensibility. The paintings are hung in recessed vitrines, a method often reserved for delicate and ancient works which, here, further establishes a dialogue with the heritage of Chinese painting.

For Hao Liang, these works explore a tension between historical evolutions behind the concept of “Eight Views of Xiaoxiang” and more contemporary cultural expressions. Geographically, Xiaoxiang is located in Hunan where the Xiang River meets Dongting Lake. However, the motif of Eight Views of Xiaoxiang moves beyond simple depictions of the natural surroundings of a particular place, finding a number of visual representations in reinterpretations across East Asia, including China, Japan, and Korea. Since the tenth century, the motif has inspired painters including Dong Yuan (934-962 CE), Song Di (1015-1080), Muqi (d. 1281), An Gyeon (b. 1400), Sōami (d. 1525), Wen Weiming (1470-1559), and Kano Shoei (1519-1592). Through research into Chinese and Western antiquity, Hao Liang assumes the role of so many scholars before him, hermeneutically reinterpreting Eight Views of Xiaoxiang with a modern eye, parodying borrowed forms to develop his own stylistic language that fits within the classical cannon.

For Hao Liang, the painting surface is not simply a material vehicle embodying space and time, but a medium for contemplations of such. Diverging from the principles of both traditional Chinese painting and linear perspective, Hao Liang relies on composition, modeling, color, and variations in light and shadow to produce multilayered perspectives within each canvas, creating unstable, non-linear spatio-temporal impressions. For example, in Eight Views of Xiaoxiang—Myriads of Transformations, Hao Liang depicts the passage of autumn into winter with the clarity of a day just after rain when all things in nature begin to change, lending a dynamic sense of time to the canvas, constructing multiple perspectival relationships by incorporating the sea, running river, landscape, and other imagery into a relatively flat space, and using bamboo, a traditional element, to disrupt viewers’ entry into the spaces depicted. In Eight Views of Xiaoxiang—Mind Travel, he combines the forms of a flat geographical map with that of a shanshui landscape. Through the warping of space and compression of multiple seasons through the inclusion of elements emblematic of those seasons, the view becomes abstract, reflecting “mind travel,” a deeply contemplative form of looking reliant on the deconstruction of any literal sense of time and space.

In exploring the basis of concepts of space and time, Hao Liang appropriates textual elements to more broadly explore the historical conceptions of painting, focusing on the potential contained within excavated traditional elements. In Eight Views of Xiaoxiang—Relics, he begins imitating a classic concept, using imagery and text to demarcate different historical periods of iconography in Chinese painting, even incorporating contemporary imagery. Here, symbols embodying varying notions of time—relics from the past, those of the contemporary and also possible future—appear simultaneously on the canvas, hinting at their intertextuality. In Eight Views of Xiaoxiang—Scholar’s Traveling, Hao Liang has organized the canvas according to Wan Ximeng’s A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, combing it with literary references found in Travel Diary of Xu Xiake, creating a vision of the “scholar’s tour.” Yet the artist’s historicizing does not stop at mere appropriations of image and text; he also revives the brushwork techniques of landscape painting to entirely reflect an alternative “world view.”

By engaging withthe long art history surrounding Eight Views of Xiaoxiang, Hao Liang explores traditional techniques and material concerns while developing the potential of canonical forms through a research-based working method. Through spatio-temporal changes and textual appropriation, he contributes to this continuously evolving visual motif, offering his own answer to the question of modernity in Chinese painting.

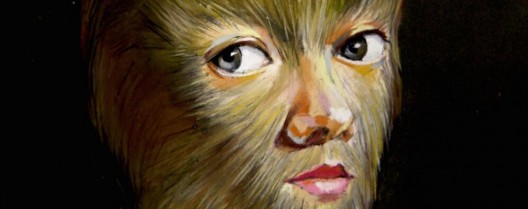

From 4 November 2016 to 8 January 2017, the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) presents “New Directions: Wang Haiyang,” premiering a meticulously produced stop-motion animation Wall Dust (2016) and five experimental films: The Proof of Existence, Communication, Golden Breath, Seize the Moment or the Moment Seizes Me, and The Invisible Hand. Wall Dust is the final installment of a trilogy, sustaining the distinct language and style pioneered in Double Fikret (2012) and continued in Freud, Fish and Butterfly (2009). Wall Dust presents the surreal world of the trilogy’s protagonist Fikret, replete with imagery that oscillates between the lonely, weird, absurd, and erotic. In the other new works, short loops presented on bulky monitors, he applies the fundamentals of stop-motion animation to video, exploring the visual representation of traces, time, consciousness, and serendipity. In these works, the creative process, like the finished film, reflects the artist’s desire to at once compress and elongate time.

A graduate of the printmaking department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Wang Haiyang combines the twinned forms of painting and animation to expand the rhetorical scope of these two media. In Wall Dust, Wang continues in his signature style rooted in sketching with chalk on sandpaper, constructing a dazzling world reminiscent of the filmic language of Sergei Parajanov in its poetic leaps of imagination. Here, the imagery and symbolism of each frame is multivalent, making a series of connections through free association, while embodying the sequential “traces” of before and after, representation and erasure.

In 2016, Wang Haiyang created five experimental video works continuously broadcast over surveillance monitors in an attempt to open new channels for contemplation. The basic formal logic of these works and their filmic language remains based in stop-motion animation. The continuous presentation of “traces” of creative production and destructive erasure eventually yield to greater concerns of temporality and existence. In Seize the Moment or the Moment Seizes Me, Wang focuses on the tension between stasis and continuity, using the sandpaper to record instantaneous moments of time, which are then erased. The buildup of each “moment” is captured, allowing traces of both time and its erasure to coexist on the same plane. Wang also combines his own life experience with that of his filmic experiments as in The Proof of Existence, for which he uses calcium tablets to smear the sandpaper white then charcoal to cover the new surface with dark circles. For Wang, calcium tablets play an indispensable role in his life and metaphorically portray an inescapable force. The traces left by the black charcoal and white calcium tablets are mutually transformative, evoking a kind of struggle that reflects the artist’s own trajectory. Similarly, episodes of aesthetic chance occurring within an arbitrary set of parameters, the semantic ambiguity created by the absence of an active subject, and the circumscribed limits of communication appear as central concerns within Golden Breath, The Invisible Hand, and Communication.

Stop-motion animation is not simply Wang Haiyang’s medium of choice but also forms the basis of his interrogation of the moving image. Within each work, he attempts to construct and dissolve the stability between static fictional images and real elements, both of which eventually appear in movement on screen.