What is the purpose of a love letter to a deceased beloved? To say everything unsaid or to re-say it?

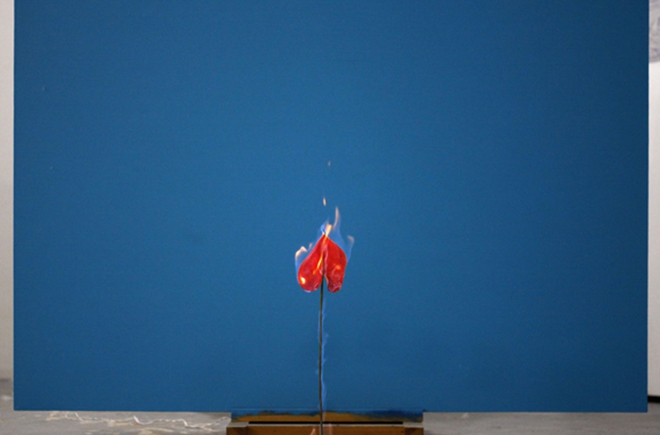

Flowers engulfed by fire, the very instant the flame takes hold before the blossom corrupts. There are fifteen in Jiang Zhi’s series, each simply numbered. Each flower is shown alone — a matching bouquet, a potted plant in bloom, a fallen blossom. Each flower is essentially different — a bouquet of roses, a calla lily, an orchid. The setting varies: sometimes a monochrome background — a red lily against a blue background; a white orchid against grey, a violet orchid against a yellow and also a grey-blue canvas, red roses and a red calyx lily against black (“Love Letters” Nos. 6, 5, 3, 9, 11) — or in the reflective corner of a steel box (“Love Letters” Nos.12, 13), or in receptacles — two long-stemmed flowers stand on a reflective metal base in respectively a jug and a vase — against almost homely textured wallpaper. Three bouquets stand in vases on an industrial floor — tiles, stairs, concrete (“Love Letters” Nos.1, 14, 15).

They are not original, are they? In fact, such images seem to exist in constant conflict between the eternal and the clichéd. In 2005 the English artist, Mat Collishaw, exhibited a series of bouquets also being engulfed by fire (“Something about the night”). Each image was gilt-framed, the frame itself scorched. It was as if history was burning, the still-lifes of the Flemish masters burning the present. But Collishaw’s blooms were corrupted by the flame, their peak aesthetic vigor diminished (is this not why we buy flowers to give — as a sign of life bountiful, if momentary — not because we know they will soon shrivel and brown?). Jiang’s blooms remain perfect (1), eternally idyllic in a way that only untimely death can bring to physical beauty. Warhol knew this too, of course, with his endless Marilyns, the counterpoint being his morbid “Green Car Crash (Green Burning Car I)” (1963) and “Electric Chairs” series (begun in 1963 and continued for the ten years) (2).

Early this year Jiang’s wife, the well-known writer and critic Wawa (Ren Lan), died suddenly, leaving behind not only Jiang but also two young children. Oft underrated, it would be easy to dismiss Jiang’s images as simply emotive, but simple they are not (compare his “Poetry of Angels” series and the flayed angels made of silica gel with the 8-minute video “0.7% Salt,” showing actress Gillian Chung’s face change from glowing smile to abject tears). Understated but always informed, Jiang, like Wawa, is also a talented art writer. And he and Wawa were always very socially observant, engaged and critical (a good example being Jiang’s depiction of Chongching’s infamous “Nail House,” where an owner held out against bullying developers, refusing to leave his house even as the earth all around it was removed — “Things Would Turn Nails Once They Happened”)(2007). With that series of works, within crepuscular settings individuals in various types of modern clothing (a motorbike suite, a wedding dress) are hit by a beam of light, lifted off the ground by it, shocked by the collision of modernity and history, symbolically echoed in their backgrounds with items such as power poles with garden temples, highways and Buddhist towers. At the impact point the light is so strong there is only obliterating, anonymous whiteness.

In 1990 the wife of Nobuyoshi Araki, Yōko (荒木陽子) died of cancer. Araki is famous for his millions of sordid photos of sordid Tokyo (particularly his popular book Tokyo Lucky Hole, 1985) but also for his semi-fictional histories of their romance — “Summer Journey” (1971) and “Winter Journey” (1991). Subsequently to “Winter,” Araki produced a series of floral still-life homages to his wife. Some were rather simple snapshots, others elaborate concoctions, such as “Painting Flowers’ with close-ups of lush blooms brightly spattered with paint. Some of these works were even titled “Love Letters.” Is it mere accident (or worse, as one critic suggested to me) that Jiang has quoted both Collishaw and Araki?

A series of still-lifes precedes Jiang’s “Letters.” These present flower stems pierced by hooks, tied with bands of fine wires, sadomasochistic musical instruments but formally also recollecting the light beams in the “Things Would Turn…” series. And that is not all: these bound sexual flowers, but also half a pig’s carcass on a plastic covered hospital bunk, an upturned octopus, two pigs trotters on a log-cutting board, a dead sheep (almost Christ-like), a heart, and a naked man, the wires threaded through his erect cock. Yes, each of these images is painful. Another series by Collishaw, “Punk Flowers,” shows flowers with punk piercings — chains and hooks. Another by Araki presents almost Helmut Newton-like presentations of women posing in Japanese aesthetic bondage —kinbaku. Note too that Yōko Araki was also a respected writer.

Here is what I think: “Love Letters” are love letters — full of yearning, loss, angst, anger, sex, tenderness, children, life itself, even work, boredom, and frustration, and not only that but also a desire to convey all these things to one’s beloved, whether futile or not. But Jiang knows the weight of cliché, of platitude, and his critic’s shade stands near him — is that enough? These are also images of what it is to be a photographer, to make an image of remembrance, how hard — impossible — it is to avoid repetition. Somehow all photos are similar, and somehow all deaths are too. Yet to the grieving, death remains as singular as love. The real question, despite whatever intentions lay behind them, is whether the “Love Letters” succeed in escaping mere platitude. In reply, the images of piercings are unambiguous, whereas with the burning flowers a certain doubt remains. Then again, love’s ambivalences lie at the bewitching centre of desire itself and death being the ultimate marker of the unattainable. It is why images of burning paragons are so powerful.

Why did you choose such clichés, my love?

For you — to provoke you.

(I would like to thank Steven Harris for his sensitive comments on an early version of this article.)

![]()