On the eve of APT7, the pioneering visual art event of the Asia-Pacific, Randian’s Chris Moore spoke with Suhanya Raffel, Director of the APT and Acting Director of the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) and Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), about APT’s first 20 years and the changing face of Asia.

APT7, The 7th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) and Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA), Brisbane, Australia. Dec 8, 2012 – Apr 14, 2013.

Chris Moore: The Asia Pacific Triennial was founded in 1993. How has the concept of Asia and the APT itself changed since then?

Suhanya Raffel: At the time of the first triennial in 1993, what constituted “Asia” [in Australia] was actually very narrow. It did not include India or South Asia and the “Pacific” meant Papua New Guinea, New Zealand and Australia. The first APT was thinking about our absolute neighbors, the immediate countries that hugged a common border, and not all of them. So the concept of Asia has expanded incredibly over the last 20 year. We stage a triennial that is defined by geography but that geography is tested every single time — we question what constitutes Asia? This time we have gone all the way to Turkey which echoes a historical understanding of Asia that has mapped Asia as east of the Bosporus. For us, it is very important to understand “Asia” as an open-ended geography.

CM: Could we understand Europe as just western Asia?

SR: (laughing) You never know! We have curated a project called “From 0–Now: Traversing West Asia” that includes artists from Central Asia for example, whereby the notion of Asia is in dialogue with Russia. “Asia” as a concept needs to be a porous entity and that is a very good thing.

CM: From inception, the APT has developed an impressive record of identifying trends and emerging talents in Asia. Looking back, what do you see as some of the highlights of APT?

SR: Over the years the Gallery has worked with amazing artists, from Australia, from Asia, and the Pacific, and that has been and continues to be one of the great energizing forces of the triennial. It was wonderful to have worked with artists — especially given your interest in China — like Zhang Xiaogang in 1996. We worked with him right at the beginning, with his Bloodlines: The Big Family series.

CM: That was the first time I saw them.

SR: Ok, there you go! We also worked with artists such as Cai Guo-Qiang, Xu Bing — and actually, apart from the APT context, we were able to acquire Xu Bing’s “Book from the Sky” for the collection. Indeed we were the first museum to acquire key works by Xu Bing, Cai Guo-Qiang, Zhang Xiaogang, and Ai Weiwei who have since gone on to become major international contemporary art figures. That early interest, the fact that we were the only museum interested in this region, has placed us in a unique leadership role in terms of developing the collection, and certainly in terms of relationships and putting this gallery on the international map.

CM: APT is still the only major visual art festival that concentrates on the Asia Pacific Region, even though that region covers a third of the planet and half its population. Obviously its structure is informed by Australia’s multiculturalism and the influence of post-colonialism, but how would you say that the APT is perhaps influencing curatorial practices in other parts of the world, including Europe and America? Do you see any trends emerging?

SR: The triennial was the catalyst for that part of the collection, and for the Gallery it has been important that the APT exists within the structure of the art museum. There are a handful of other major recurring art biennales or triennials with a similar structure. Festivals like Venice Biennale or dOCUMENTA have very different infrastructures.

CM: Could you expand on the role of acquisitions in the APT?

SR: The APT offers the Gallery an opportunity to consider collection building. This is an important part of the curatorial practice that we have developed. Our in-house curators have always worked on the Triennial with co-curators, advisers and others in the region, and the result is a collection that is peerless in the area. And today we are celebrating twenty years of this project. It has given us a collection we could never afford to collect now, certainly, but it has also provided us with a twenty-year history. Europe and American have woken up to Asia and the Pacific and realize that it does comprise a third of the planet and half its population and that it does matter what happens there.

CM: What are the key themes behind APT7?

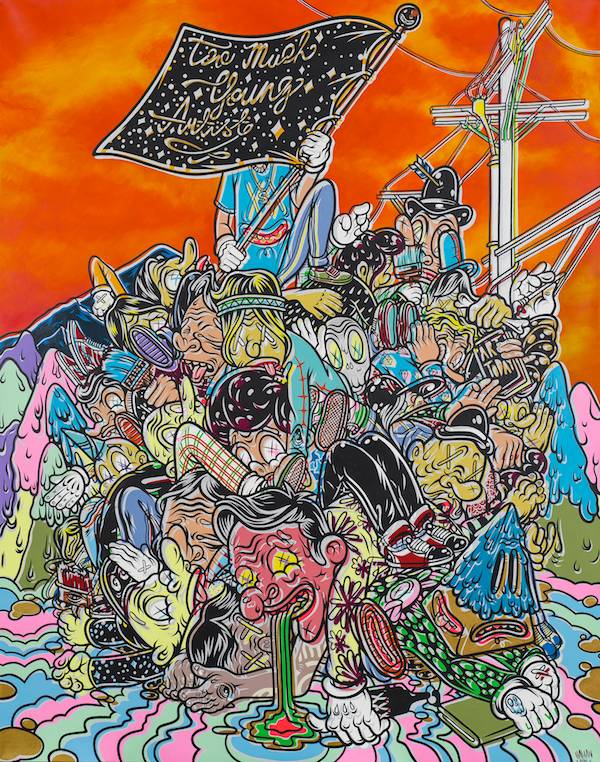

SR: Every single APT, the themes and ideas emerge from our research travel. Some ideas that are particularly strong this time include an exploration of ephemeral architectural structures, the significance of sustainability, the importance of painting in its most expanded forms — from the Spirit Houses of the East Sepik, Papua New Guinea, which are full of painting, through to Zhou Tiehai’s suite of 158 paintings, Le Juge.

CM: One of the unique aspects of APT is its platform for Pacific art practices, particularly from Polynesia. This time APT will focus in particular on the art of Papua New Guinea. Is this region still neglected?

SR: It depends. Papua New Guinea, and West Papua, too, have incredibly strong cultural practices that challenge definitions of contemporary art. That is something APT always looks at closely — what is contemporary art? It is a question we return to every time. These artists [from Papua] have culturally specific practice, customary practices, and when we travelled to Papua to commission the works, part of that project was to bring artists here for APT7 and develop the work for the show. The result is an extremely rich project.

The Pacific is an important part of the world, and the kind of art being made there brings into sharp focus how we reflect on our definitions about contemporary art, who is a contemporary artist and how do they make work. This is part of a wider dialogue originating from Australia’s Indigenous artists.

CM: The previous APT also had a recordings and music from the region.

SR: Yes, “Pacific Reggae,” which was directed by a range of local political responses across the Pacific that used the form of reggae to express these ideas.

CM: One of the most refreshing and thoughtfully curated aspects of APT6 was its children’s program, which was engaging but never patronizing, frequently intelligent and huge fun. What does APT have planned for children this time and how do you see its role within APT?

SR: The QAG and GOMA have a long-term commitment to children. We absolutely believe they have an equal right of access to the museum as any adult. “Kids APT” began in 1999 and we’ve never looked back. It has become an intrinsic part of APT and most of what we do at the Museum. It’s not an after-thought and is curated in collaboration with artists from the inception of the APT project. We have thirteen Kids APT7 projects this time.

CM: Finally, can you tell us about the yellow boxes sticky-taped together?

SR: Yes! As I said, one of the themes of APT7 is ephemeral architecture and sustainability, built environments. Richard Malloy uses recycled cardboard to create an interactive installation. We have been collecting boxes from all over the place — it’s a giant form you can enter which is also a sculpture while considering ideas of sustainable architecture. Cardboard boxes are forms of shelter, it is a durable material, and the work offers the viewer an opportunity to reflect on bout built environment. And it is fun. APT often has very serious themes while also being full of joy and celebrating the great creative energies of being in the world today.