I am sitting in the Grand Hyatt’s lobby, enjoying the more discreet pleasures of being on the right side of the Great Firewall of China: tweeting, re-tweeting, posting, sharing, liking. I am waiting for Mario Cristiani, one of the three founders and directors of Galleria Continua (the others being Lorenzo Fiaschi and Maurizio Rigillo)—which happens to be one of my favorite galleries, and who also happens to be Italian, like me.

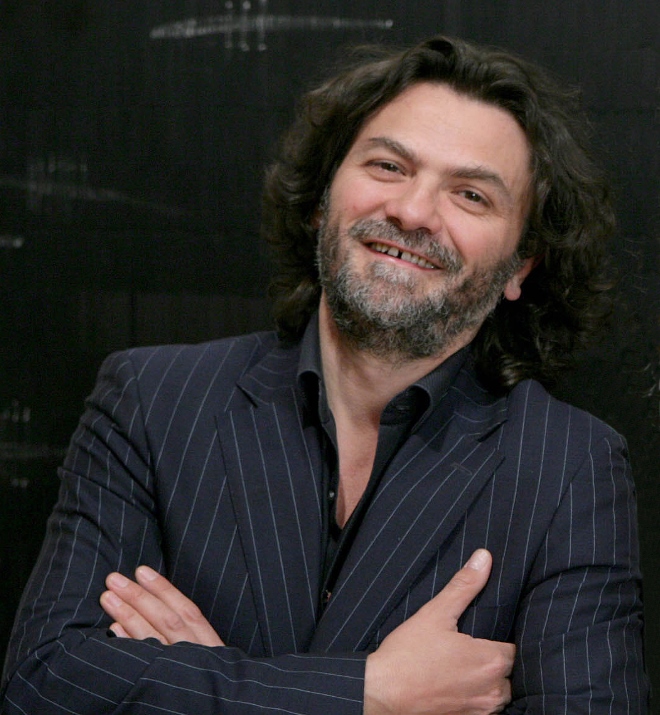

Mario meets me in the breakfast-room of the hotel a few minutes later, and we break the ice with small talk while he serves himself a generous portion of fruit, yogurt and other healthy marvels out of the cornucopia laid on the buffet table. Once we are seated, I place two microphones very close to him, as his voice is quite low (I think because he is struggling with jet lag). He orders coffee and I decide to start off with a question related to our common roots.

Girolamo Marri: Continua was founded in San Gimignano, Italy; it later opened a space in Factory 798 in Beijing and in 2007, another one some 60 km out of Paris. With these bases, you can keep the pulse of two situations that seem diametrically opposite; the Italian art market slowing down in its critical spiral, and the Chinese relentlessly growing and growing. Do you read the situation as such?

Mario Cristiani: No, I don’t see it as such. “Market” is always something complicated to talk about and identify territorially. In my own experience, it’s always people in different parts of the world who act simultaneously to generate the market. We take part in about 20 art fairs every year, so really our collectors are transnational.

GM: In the gallery space, you mostly let the artists run wild.

MC: What we aim for in the gallery space is really letting the artists do their art. Then, obviously, the outcome needs to be shown to people who can’t reach our relatively remote premises. The story needs to be continued, so to speak, and this happens in the fair. During the past few years, we have started promoting our artists online, too. It’s working well, even in terms of sales.

GM: There is much talk of the parallel growth of biennials and art fairs in the past few years. You seem to walk both paths in a leisurely way. Your exhibition spaces are so big that you can afford to have some sort of “biennale” attitude in your shows, with large installations and unconventional projects, while at the same time, as you said, you’re very present in the art fair system. And it’s has been like this for a while—you were ahead of time in this sense.

MC: Continua has always been directed in this frame of mind. Most importantly, the theoretical and practical duality between local and global was also clear in our minds right from the start.

We started in a former cinema in San Gimignano, a medieval town in Tuscany that attracts large amounts of tourists for its historical heritage, and we aimed to channel new energy into this celebrated dead body. The name Continua originates from this will to establish a continuation between past, present and future.

Quickly, our interest grew towards art fairs and biennials, which we consider as means to establish cultural tourism in places that traditionally lack it, and where people desire something that transcends the immediate and the mundane.

GM: Among other examples of this inclusive way of conceiving your effort, I would list Sphères, a series of exhibitions you hosted in your huge space of Le Moulin, near Paris, inviting other galleries to present work by their artists in events which, again, are more reminiscent of biennials than of regular gallery shows.

MC: Well, artists need to have a degree of freedom and be allowed to work in different environments, and not just with their representing gallery all the time.

GM: In Europe, I have found there is often a counterproductive obsession with exclusivity; I have met a few artists who have felt suffocated by the petit-bourgeois mindset of paranoid gallerists. In China, I see instead the opposite happening, with no exclusivity contracts between artists and galleries, or contracts that are worth no more than used scratch cards and artists flying around all over the place…

MC: …We never even bothered making contracts…

GM: …Well, maybe it’s something that touches more the younger or smaller galleries, which sometimes manage to make a young artist emerge and, as soon as that happens, a more powerful gallery makes the artist an appealing offer of money or museum shows or whatever, and the latter has no problem abandoning their original patron. Has anything like this ever happened to you? Have you ever stolen artists from other galleries here in China?

MC: Oh, we steal artists everywhere, not just in China. (I admire his poker face as he says this). Now, seriously, we tend not to formalize our relationships too much and base them on trust; if occasionally we get screwed, you know, never mind—it wouldn’t be the first nor the last time. When we started Continua, each of the three of us chipped in with 1,000,000 Italian lire (That sounds like a lot, but before Italy adopted the euro as its currency, this corresponded to no more than 4,300 CNY!), and we risked bankruptcy a few times. We have always enjoyed taking a few risks to do what we like to do. And we believe in trusting ourselves and the people we work with.

What I fail to grasp is why not many others play this game the way we do. We’re being quite successful at it, so why don’t others try and have the same open approach? I think the art world would benefit from it.

GM: In moments of economic crisis (as this quite evidently is), people should try to innovate rather than staying stuck to their securities which, in the end, always prove to be not-so secure, after all.

MC: Promoting art and artists in my mind is kind of risky by definition; it should always take you to new and unexplored territories, and inherently there is great risk of failure in that. On the other hand, no one is forcing you to do that.

GM: This sounds to me like the argument an artist, rather than a gallerist, would commonly make—not to rest on your victories but always to push your research further.

MC: Life goes onward, so should you.

(This man is starting to sound like a wise person, which makes me a little uncomfortable.)

GM: You are showing Loris Cecchini’s work in your Beijing space right now—how’s that going? How did you decide to do a solo show for an artist whom, I imagine, doesn’t have many “credentials” in China? [Ed. the interview was conducted during Art Basel Hong Kong 2013]

MC: We don’t really make that many calculations with regard to who we are showing in each space and what the outcome is going to be. We show who we like, trying also to make our exhibitions circulate through our three spaces.

GM: If you were showing more of your Chinese artists in your Beijing space, I imagine it would be much more profitable for you, though.

MC: To us, opening a space in China was mainly a way to create a bridge between China and Europe—a bridge that would go both ways. The artist Chen Zhen really believed in this idea and pushed for us to do it. We showed his work in 2000, just before he passed away.

GM: Your spaces have been the stage for some important closures by Chinese artists: Chen Zhen in 2000 but also Gu Dexin, who had his last show in your 798 space in 2010 right after announcing his retirement from the art world. I’m not suggesting you sort of jinxed it for them of course (I make this clear, because Mario has raised an eyebrow), only that these have been really important moments.

GM: I heard your gallery was infested by rats when you showed Gu Dexin’s “2006-09-02” piece, where apples were arranged on the floor and left to rot.

MC: A few snakes, too.

(With a few twists and turns which I’m finding difficult to report here, our conversation shifts now to art in public spaces.)

MC: Although we still haven’t implemented it, we have a desire and hope at some stage to help make use of these huge spaces and structures in China that are somehow culturally empty. Art is a glue that holds people together. Rather than pushing people to be together in order to consume, eat, buy or something like that, you get them to be together because of beauty—and for free.

I don’t just mean museums, but art around the city—fully public. This is in accordance with the idea—a very Mediterranean idea—that the city belongs to everyone, and that people can enjoy beauty for free. A museum, to me, is instead a rather northern European idea; you have to enter a place, you have to make yourself recognizable, pay a fee, and only then you are allowed to see art. It’s “sect” logic rather than “community” logic. Public art is instead much more reminiscent of the agora—the Greek square where people used to meet for all public affairs as well as for leisure; as long as you’re alive and you’re there, it’s for you and for free.

GM: Speaking of the connection between art and the public, please tell me about the Moataz Nasr exhibition you held in your 798 space. That was quite a politically charged endeavor.

MC: I think we sold almost nothing…two works…maybe one. (He giggles) But it was important for us to do that show. It told of a search for freedom, of an attempt to free oneself from a certain situation—It’s true that the example of Egypt could be debatable as now, over a year after the uprisings of the Arab Spring, people over there find themselves in a position that is arguably worse than before.

I believe art can be also a source of alternative information. Moatasz’s show was meaningful in these respects—it was a special way of letting people here know about something happening elsewhere, and to show that it isn’t as far away as it seems, really.

For example, though one tends to ignore it, there is actually a large number of Muslims in China—I think at least … (We discuss the exact figures for a while, both getting them very wrong. I can now confirm that something between 1 and 2% of the Chinese population is Muslim—or 20 million people). Moatasz’s work was bringing attention to them, too, and what they share with other Muslim communities throughout the world.

GM: Did you have problems with censorship for this show?

MC: Not at all. We never really had any problem with censorship in China, except once in Shanghai when we presented a Kendell Geers statue of the Buddha covered in text saying “Fuck!”, and it was removed—more for religious than political reasons, I’d say.

GM: In the Shanghai Art Fair they are—or they were, who knows—stricter than in other places, my impression being that they’d like to keep Shanghai a contradiction-free city—eye-candy for tourists.

MC: Maybe, but with the Kendell Geers’ exception, we never had problems there. A place where we actually had problems was in Dubai.

GM: Okay, let me conclude this interview with a really standard question: Who’s an artist you’re not working with at the moment that you’d like to work with?

MC: Someone I’d really like to work with—and it might happen in the future—is Carsten Höller. And here, someone whose work I really like is Qiu Zhijie (we both struggle abundantly with the pronunciation), who did a really good job with the Shanghai Biennial.

GM: Thank you, I’m very satisfied with what we talked about—I hope the recorder actually worked.

Once I switch off the recorder, we keep talking over coffee about all sorts of random yet interesting topics, I remember distinctly a few minutes spent discussing intellectual honesty and ideals in art, for example.

At the end of our breakfast, the impression left on me by Mario Cristiani was that of someone who believes very much in the ethics of what he does, and who is not particularly bothered by conventional thinking and attitudes, or by other people’s expectations. Naturally, I felt skeptical about all this. I find it too difficult to believe that people can arrive at even relatively high positions in almost any field without being shrewd, disenchanted and very weary.

A couple of evenings later, though, my positive opinion on Mario was much consolidated when I met him again in the industrial area of Chai Wan, where Continua and another three galleries had organized their party in a warehouse. It was sweltering hot and very crowded; Pet Conspiracy was playing and there were very good cognac cocktails offered by a sponsor. At one moment, Mario climbed on stage with his shirt completely open, and loudly welcomed everyone to the party. Then he jumped back to the crowd and I lost sight of him for a while, until I found a little opening in the crowd of possibly drunk yet quite composed people. In the middle of it, keeping people at a distance with his whirling arms and naked torso, covered in sweat and oblivious to everyone around him, Mario was dancing like a happy madman. I patted him on the back and decided on a full thumbs up.