What’s a king to a god?

What’s a god to a non-believer

Who don’t believe in anything? (1)

Postmodernism is a late-20th-century movement in the arts, architecture and criticism that was a departure from modernism. Postmodernism includes skeptical interpretations of culture, literature, art, philosophy, history, economics, architecture and literary fiction. It is often associated with deconstruction and post-structuralism because its usage as a term gained significant popularity at the same time as twentieth-century post-structural thought. (2)

Earlier this year the German newspaper Die Welt published an exclusive interview with artist star Anselm Reyle in which he announced his temporary retirement from art. When and how he plans to return—if at all—as an artist, the 43-year-old leaves open.

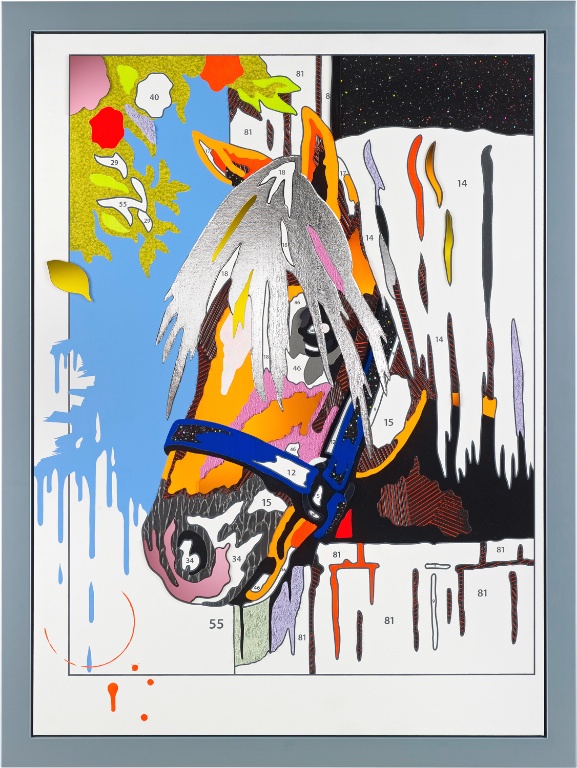

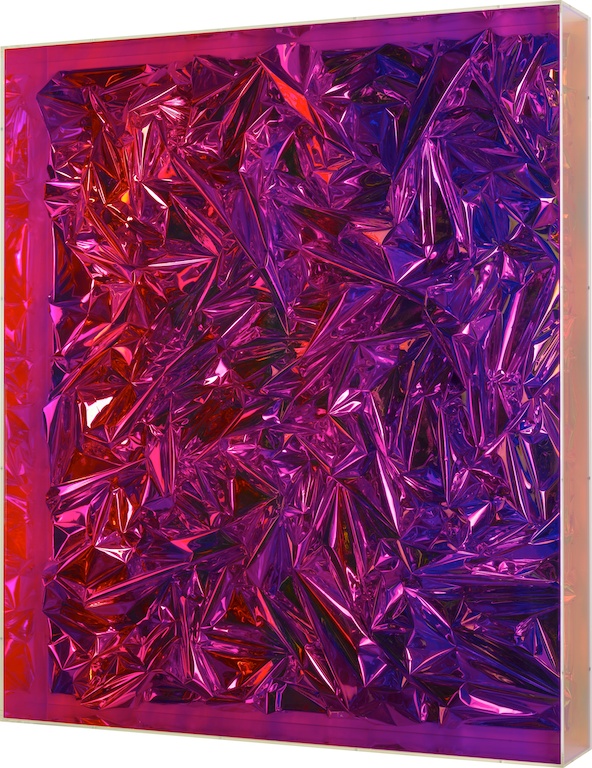

Anselm Reyle, “Untitled”, mixed media on canvas, metal frame, lacquer, 80 x 69 cm, 2008 (© Anselm Reyle; image courtesy the artist and Almine Rech Gallery)

Reyle is one of the most prominent German artists and renowned for his foil and strip paintings—an art that questions the aesthetic death, the end of modernity. It’s about bad taste and the question of who defines bad taste, and whether one can save this distinction through high art. (3)

“Fuck Art, Let’s Dance!” I was never convinced that Postmodernism didn’t believe in anything. PoMo believed in too much; it (we) liked everything and strove to prove our love by quoting and appropriating all. As for skepticism, that comes with style: How do you prove style? You don’t just give it away, you earn it. True skeptics may even doubt the reliability of their own senses.

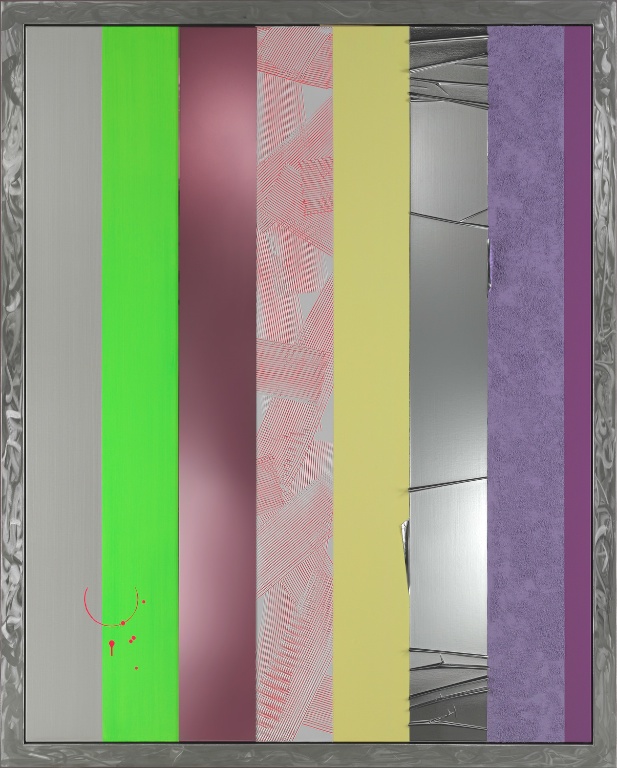

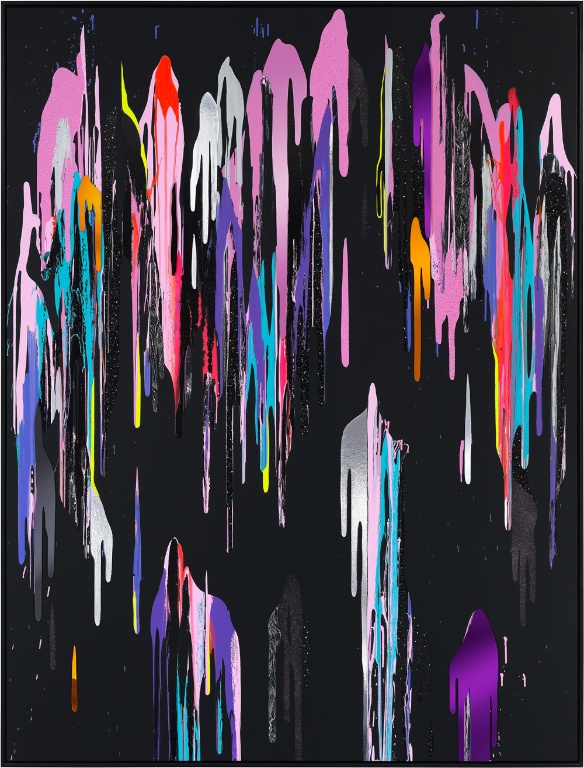

Anselm Reyle, “Untitled”, Mmxed media on canvas, wooden frame, 225 x 170 x 6.5 cm (framed), 2011 (© Anselm Reyle; image courtesy the artist and Almine Rech Gallery)

This text is in lieu of a discussion Chris Moore wanted to arrange between me and Anselm Reyle. The main reason for this discussion were some striking formal and material similarities between aspects of my work and Reyle’s. I confess that at first, I was pissed off at the similarities; Reyle was an international art star, and I felt like an Australian nobody, even though my work predates Reyle’s. We have had the same influences and sensibilities, but his were valued, whereas mine seemed relatively valueless outside Australia. Art is what makes it into the Archive AND what is left out. Or perhaps there is no more “Art” as such; all that seems to be left is a value system which regulates the symbolic marketplace of the archive and the art market—they appear to be the same place now, with no real divide. Just as there is no real material divide between what is Art (crushed Mylar, Zombie gestural “brushwork”, shiny surfaces, expensive acrylic cases) and what is Not Art. Just as there is no real divide between “Fine Art” and “Popular Culture”—again the same terrain except for increasingly desperate attempts at brand differentiation to maintain market value. Let’s face facts: with arguably no real formal innovation in art for decades, we are on endless repeat. This is novelty and market activity masquerading as culture, but this time with internet access and a pretence of “the global”.

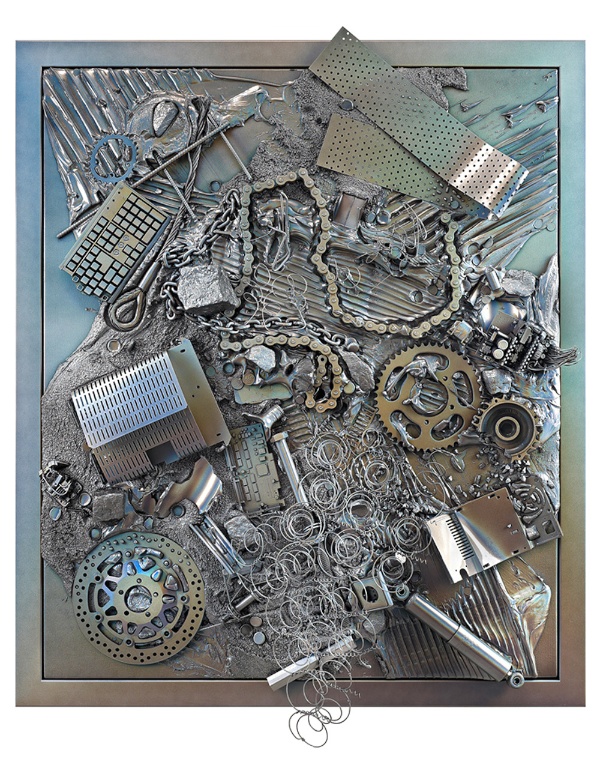

Anselm Reyle, “Untitled”, mixed media on canvas, acrylic glass, 71 x 60 x 10 cm (framed), 2010 (image courtesy the artist and Almine Rech Gallery)

Anselm Reyle is also an artist who ran a studio of up to 50 assistants; times were, the “factory” swallowed 800,000 Euros per month and sculptures cost more than 1 million in production costs alone. In this context, “Die Welt” asked Reyle: What was the most surreal moment of this boom? Reyle:

“The whole situation was surreal. And not necessarily just pleasantly surreal. It’s not that I was happier at this time. Not at all. The total hype-phase, where the images at auctions suddenly became extremely expensive, immediately entailed developments with it which were rather unpleasant. For example, scrambles among the galleries with which one is also on friendly terms. Or the absorption of my persona at openings of my exhibitions; those are the things I don’t like to be reminded of.” (4)

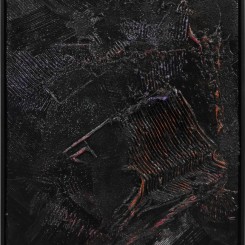

Reyle’s retirement could be a milestone gesture (a work of art in itself). I admire Reyle. Why? Well, his work shows us something new: That one needs to test the limits of the question to an end to Art (aesthetic death) through one’s own self. My own initial upset at Reyle’s success became a final culmination of my own distrust (skepticism) about capital “A” Art. After decades worrying about who may have ripped me off and paranoid about my place in art, I suddenly saw some release in that pretty, shiny, crumpled Mylar covered with cum shot drips of paint. You can’t achieve Rock n’ Roll attitude except by making it. Yes, I had already made such work, destroyed electric guitars in thick gestural black paint; and all but one have also admitted defeat by the international art market—but we do have options, and those options become visible only after an act of rejection of that which consumes the individual.

Anselm Reyle, “White Earth”, mixed media on canvas, metal frame, 255.2 x 204.2 cm (framed), 2008 (© Anselm Reyle; image courtesy the Artist and Almine Rech Gallery)

If style and attitude are release, then we will be released: NEW SINGLE OUT NOW! So what of Reyle’s decision to retire? We can now see that underneath the media entity of Anselm Reyle Art Star was an individual prepared to explore the world of deep surface by wholehearted immersion in an effort to discover a glimpse of sub-medial underpinning. Reyle’s retirement was a truth-telling about the financial and personal stress of his career, and it shows him to be more of a serious German artist than many had envisaged. In Australia, Kunst is viewed with a (healthy?) skepticism, but in Europe and Germany it still holds an elevated status. Reyle just got tired of it all, and got out before the next crash and burn end of the cycle.

“As I said, I am solely interested in the politics of immortality – how one becomes a pure soul, an indestructible mummy, a living corpse.” (5)

The observer develops a desire to know what is really concealed behind the medial surface of signs—a media-theoretical, ontological, metaphysical desire. No doubt, the question concerning the media carrier is nothing but the substance, the essence, or the subject possibly hiding behind the image of the world. For Boris Groys, it is one’s worldview that needs to be altered, because mere rejection of the mainstream world leaves one merely mortal: “If one is merely mortal, to escape one’s position in the world is impossible.” (6)

Aesthetic suicide is an ultimate truth to one’s self, but it is also an opening gambit (Hullo Kurt)—the corpse keeps living, but is stripped of the need to continually “re-enact” the quest for truth; that is, to keep producing more examples of their allegiance, their Faith, more art, more product. Art now is only a space where profane objects enter the sanctity of Art, either to be lodged in the archive or leave the archive. Neither the objects nor the values have any inherent meaning themselves outside the closed systems of specific contexts. This is why Australian art has no international value; instead it arrives and departs: Art with no specific context. Human beings can do this, too; the artist’s body, their identity, can arrive in and depart from the Archive. Better to retire or remove one’s self before one is pushed. As Boris Groys reminds us, “The decision to be human is no different from that which validates a work of art as a work of art.” The human being, in other words, is essentially a work of art. (7)

So, what would it mean to be a work of art? By this we don’t just mean a wondrous OTT creature who fashions themselves as a living artwork, as do artists like Orlan or Gilbert and George or Jeff Koons. What is meant is more nontheatrical people/artists. What Boris Groys is interested in is the state of self-loss or body-loss akin to the experience of the heavy internet user, gamer, Second Lifer—a state analogous to the practice of reading a book. Only in this state can we break free from the “flesh” of the world and transcend the Market of ideas and commerce that basically rules all of what we now term Art.(8) As usual, for Groys it seems a quasi-spiritual quest, but one without the Left and the Right’s continuing belief in “authentic”, “genuine” or “resisting” forms of art (the Right resists as much as the Left, the two forms of thought are basically the same).

For me, Postmodernism was freedom and empowerment; a freedom to like what I liked and to live my life as I needed to. One of Anselm Reyle’s last group of works was a set of sub-Memphis style couches, a smart (perhaps too cute) steal. Memphis Design is synonymous with 1980s postmodernism. It’s too easy to equate Reyle’s quote of this supposed “dead” style with its current resurrection by kids actually born in the ‘80s as some aesthetic death and rebirth, although Reyle stresses he’s in maybe-semi-retirement: the King may yet return. No, the truth is that Postmodernism never left. In fact, Modernism or the pre-modern never left us; they are all still with us, existing in the archive and in life and its objects (the Real) on continuous, layered planes—like consciousness itself.

“Modern society does not survive through reason, but through evolution.” —Norbert Bolz (9)

Let’s end with the genealogy of Jay Z/ Kanye West’s Grammy winning No Church in the Wild. Not only is the song collaborative, it also showcases singing and lyrics from Frank Ocean and The Dream. 88-Keys and Kanye West handled the production and the song samples from “K Scope” as performed by Phil Manzanera (the guitarist of thoroughly postmodern Roxy Music), “Sunshine Help Me” as performed by Spooky Tooth and “Don’t Tell a Lie About Me and I Won’t Tell the Truth About You” as performed by James Brown. No Church in the Wild was used in the promotional ad and end credits for the film Safe House, the promo ad for recent The Great Gatsby and in an advertising series for the 2013 Dodge Draft. A music video for No Church was filmed in late 2012 in Prague by the Greek-French director Romain Gavras. No wonder No Church is described as ‘cinematic’ in tone, the way it ‘impacted’ on the music scene (love that term); the whole thing is a postmodern tour de force of appropriation, quotation and re-contextualization. Amen.

Scott Redford (b.1962) is an artist. A major retrospective of his work was held at the Queensland Art Gallery Gallery of Modern Art in 1010-2011 “Scott Redford: Introducing Reinhardt Dammn“. He lives in Berlin and Brisbane.

NOTES

1. Frank Ocean in “No Church in the Wild” by Jay Z/ Kanye West.

2. Wikipedia entry on Postmodernism.

3. Boris Groys, Under Suspicion, Colombia University Press, NY; translation by Carsten Strathausen, 2012 (originally published in German, 2000) p. xiv. This text is indebted to Strathausen, especially his Translater’s Preface: Dead Man Thinking.

4. “Ein ziemlich befreiendes Gefühl!“, Anselm Reyle interviewed by Tim Ackermann und Cornelius Tittel, Die Welt, 6 February 2014. English precis on the (n d ks) blog: link.

5. Groys, op cit.

6. ibid.

7. ibid.

8. ibid p. xxviii.

9. POLEMIC ALERT: I engage in polemic. However, Groys expressly warns against equating the current market situation with the Economy. “(The cultural) economy in this sense is not the same as the market. It is much older and more comprehensive than the market, which represents only one specific innovative form of the economy”; ibid p. xviii.