This piece is included in Ran Dian’s print magazine, issue 3 (Spring 2016)

The most precious part of an artist’s personal experience lies in self-reflection and the subsequent representation that is later transformed into collective memory. Born in the southern Chinese province of Yunnan in 1959, the artist Tang Zhigang went on to have experiences in the military that left him with a deep understanding of the country’s socialist system. Yet his unbridled nature turned this understanding into doubt and questioning. Tang presented the contrasts of reality farcically through his paintings of the late 1990s and early 2000s, in which small children play the roles of political or military figures in different official scenarios. The works’ cynical motifs and cute-yet-disagreeable visages met with success on the market. But commercial success turned sour for Tang, forcing the artist into a vicious cycle of repetition. When fatal illness threatened him in 2009 (an experience he survived), it was as if he had awoken from a dream. He left the madding crowd behind and retreated to his hometown in Yunnan, where he found new inspiration and vast changes for his life and artistic practice.

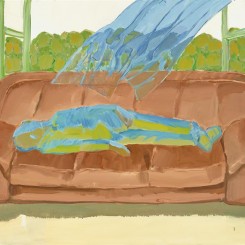

唐志冈,《世像:读书》,纸上广告颜料,55.5 × 79 cm,2013(图片由艺术家和汉雅轩画廊提供)/ Tang Zhigang, “WorldPlay: Reading”, poster color on paper, 55.5 × 79 cm, 2013 (courtesy the artist and Hanart TZ Gallery)

Graduating from the People’s Liberation Army Academy of Art in 1989

The PLA Academy of Art was formed by the army in 1949 after China established a relationship with the Soviet Union. This type of academy only exists in countries such as the USSR, North Korea, and China. Its main academic function is to teach students how to portray revolutionary history through art. Realism was very popular in the USSR. The representative Chinese revolutionary history artists from this era all had something to do with the academy.

When you are admitted to the academy, you have two identities: soldier and student. Once you are admitted, you become a soldier, and you are provided for. When China resumed the gaokao admissions process, many people signed up, but very few were admitted due to the strict background-checkprotocols. It was very fashionable to be in the PLA at that time, and being admitted to the PLA Academy of Art was to be the the elite among the fashionable. Yet many talented young people went into the academy and did not succeed because by the 1980s its teaching methodology was outdated. There were very few opportunities for exhibition.

Much like in North Korea, the PLA Academy of Art included child soldiers. If a primary-school student had talent in singing or dancing, then they would put a uniform on him. Only in countries like this would you be able to say, “When I went to university, some of my classmates were children.” In fact, I really envied those child soldiers. I was jealous of them for being able to wear uniforms at such a young age. They didn’t need to worry about food or clothing, and they lived collectively.

When you live in that kind of collective environment, you unconsciously submit to collective life. Life in the military is a very orderly form of collective life. In the 1980s we were exposed to new knowledge and philosophies that had a close relationship with my painting. That’s when I discovered that my life was very contradictory to this new knowledge. My experience in the Vietnam War had even more of an impact. All of my education about heroism and collectivism was turned on its head in that war. When you’re twenty years old, it’s an intense shock. I wasn’t prepared at the time. All I could do was ask, “How can this be?”

After I graduated from the Academy in 1989, I wandered around in Beijing during what happened to be the most turbulent time in China’s recent history. My classmates and I who graduated that year were very strange—none of us wore uniforms. I dressed like an artist, and looked exactly like a CAFA student. My hair came down to my shoulders, and I wore whatever I wanted. I was a product of the liberated 1980s. That was a really difficult time, and the nation was in turmoil, as if there was no tomorrow.

There was a huge avant-garde art exhibition in 1989 at the National Art Museum [“China/Avant-Garde”]. Objectively speaking, the development and growth of contemporary art in China has happened entirely within the nation’s official art system; it is in no way the grassroots movement many of us would like to see it as. How could such an important event be held at the National Art Museum without a nod from the authorities? It wasn’t like nowadays, when anyone can do a show at 798 [in Beijing]. Contemporary art in China was being nurtured from the get-go. If they wanted to censor you or wipe you out, it would have been the easiest thing in the world.

All the important players on the scene at the time had some relationship with the authorities. The student protests were a symptom of growing momentum from liberated thought and culture. Contemporary art was a result of that liberation. I think the two are related, but after it happened, the prospects for art were not good. There were fewer chances to promote and report on art. Art Monthly was adjusted. It used to be very contemporary, extremely avant garde.

Probing Within

I wondered if I should leave the country. I knew I had to pass my English exams. None of us studied English at school. We didn’t even know our ABCs. I had to feel my way blindly, on my own. I bought a little voice recorder, and began with volume one. I rented a shack for 70 RMB a month—one of those shacks where farmers kept their coal. In that little shack I had a bed, a square chair by the door, and a kerosene cooking stove. Between the bed and the wall I had a round table and a chair for studying. I wasn’t on active duty at the time, and took no military allowance. I worked for a living, sketching advertisements for a bit of money. Life was hard. I lived on pickles. I remember one of my classmates in Beijing brought me a meat dish from home once. I had been one of the most talented students in my year. How was I reduced to this? Suddenly, luck wasn’t on my side. It was tragic. I lived like this from the end of 1989 to 1991.

That era was very tense. There were no public spaces. At night, all of Beijing was subject to martial law. For an entire year, you would hear sirens in the night. Everyone watched television at home every evening. That was the overwhelmingly popular form of culture for Chinese people at that time.

I had left the collective and existed in an individualized state. So all of the later work I did about that time period has to do with individual existence and collective narratives. I did some work when I first graduated in 1989, and some more when I returned to Yunnan from 1992 until 1994. It was impossible to show that kind of work at the time. The government was tense because of what happened in 1989—they were afraid they wouldn’t be able to hold it together. As a result, all of the work being shown at the time was about life in the villages—shepherds singingsongs and life in the fields. It was like life in the military—individuality was impossible to express; it was all stored in artists’ studios.

Yang Xiaoyan, Gallery’s editor in chief, saw my paintings around that time. He asked my why they looked so much like so-and-so’s back in Beijing. He said they lacked feeling, but then he saw some of the dust-covered army paintings I kept in the corner, and said they were really good. He asked me why I didn’t paint more of those. I told him there was no chance of showing them. The army would never show them, and there was no audience for an artist who painted the army. Then, when I did show them, they got a huge reaction. A lot of my industry friends told me it was the first time they had seen such portrayals of soldiers in the history of Communist China. Paintings of soldiers used to portray them as the nation’s war machines. The artists never looked at them with a human eye. Even though I was raised within the system, deep down, I suppose I was never of the system.

I asked Mao Xuhui to write an essay about me. Chen Tong wrote one too, later. He came up with a term: “post workers, peasants, and soldiers era.” “Workers, peasants, and soldiers” was a revolutionary catchphrase, but in my time, we were already in the “post-” era. We talked about soldiers differently. It was a cultural phenomenon at the time. It was very brief, and was never magnified or extended.

When I started showing my works I was still a soldier, but when I started attending Yunnan Arts University the subject was no longer based on my life experience. I wanted to keep painting them, but there was no truth to it—I had to rely on photographs. I used to work in propaganda, and I had to shoot a lot of photos to lay out a set. I found it really interesting to reminisce about the people in those photos. When I was bored, I began painting the meetings we had—the facial expressions, people of all ages and identities, the phoniness of those carefully laid out scenes.

In fact, what I painted was true to life. Those meetings were real, and those people were real, but when a photograph is turned into an artwork, there is a monumental shift. If you show someone a photograph, nothing out of the ordinary happens, but if you turn that photo into a painting, it acquires a heavy sense of history. There is tension in the painting, and an ironic cast to the atmosphere. So some leaders went to question the magazine editors who had published images of my work—this was around 1996, 1997. Around that time I was teaching some of the soldiers’ kids to paint. After this Adults in Meeting incident, those kids raised their hands in front of my paintings so that they could speak. I looked at them, and looked at the paintings behind them and thought to myself, I should switch the adults out for the kids—paint the kids in there having a meeting. That way, the leading cadre members wouldn’t be unhappy anymore, right? So that’s how the Children in Meeting series happened. After I did the first one, I realized it had nothing to do with reality any longer. Yet the surrealist painting truly reflected the bizarre tensions of that era. The painting offered excellent commentary on the relationship between art and life. In that environment, Children in Meeting still caused a lot of tension. No one had a talk with the editors, but they weren’t happy about it, either.

I’d already succeeded on the market by that time, though. Children in Meeting was pushed forward by that momentum, and became a dark horse commercially. I didn’t want to do them any more, though. I couldn’t see the relationship between exhibitions and art. It was like painting money—a painting for a stack of bills. Contemporary art in China was very “in” at the time. Fashion was important, the market was important. The ego of the great nation of China had to be propped up with a hundred-million-dollar price tag to demonstrate the magnificence and endurance of our culture.

Though “a dark horse,” I wasn’t part of the 1985 Movement, and I didn’t participate in any of the post-1985 stuff. I didn’t participate in any of the large-scale international exhibitions that were the standard for any successful Chinese contemporary artist. I just happened to exist as a contemporary of that time. I walked with them, but I kept to myself on the sidelines. After my show in 2009 at Gallery Hyundai in Korea I got sick. I couldn’t paint at all. It was a question of life or death. The doctor told me I had cancer, that I only had two or three months to live. Lots of people were trying to schedule me for exhibitions, but I couldn’t do them. I lay on my sickbed for a long time, thinking, reflecting. I thought about how I would forge a new path away from the impression I had given people in the past. I began looking to nature. I did some landscapes, some sketches. I was hospitalized several times, until around 2013. In 2014, I came back to life. It all feels like a previous life now, as if that Tang Zhigang doesn’t have much to do with who I am today.

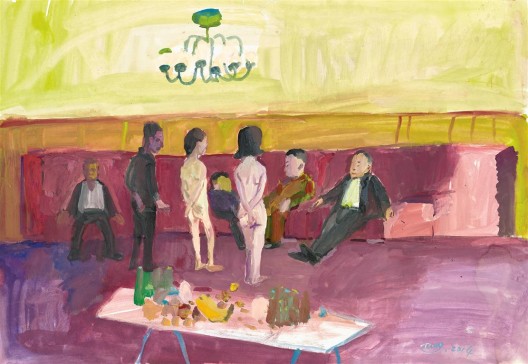

唐志冈,《世像:困顿》,布面油画,109 × 148.5 cm,2014(图片由艺术家和汉雅轩画廊提供)/ Tang Zhigang, “WorldPlay: Enervated”, oil on canvas, 109 × 148.5 cm, 2014 (courtesy the artist and Hanart TZ Gallery)