The avant-garde composer and artist Tony Conrad passed away in April. A number of his obituaries printed his passage on discovery: “When I have this feeling that I’m working in some territory I can’t clearly identify, I feel enormously encouraged. Because it means that I’ve found my way to something important that’s not been recognized,” he said.

I spend most of my time talking online—to editors, to artists, and to musicians. I am usually discussing a review or essay, interviewing, or working out a long-term collaboration. I have no choice but to meet them online; they are blossoming in little coves all over the world, in Beirut, in Bergen, in Dubai, in Beijing, in Lahore, in Taipei; in Cape Town and Berlin, Paris and Amsterdam. Some of these people are very successful, but you would not know it; some are just starting out on their creative paths. Some of them feel like old friends after a single conversation while some remain, after years of talking, like unknown quantities. But to my ear, they are often much the same in one way, their tone: focused and urgent and relentless.

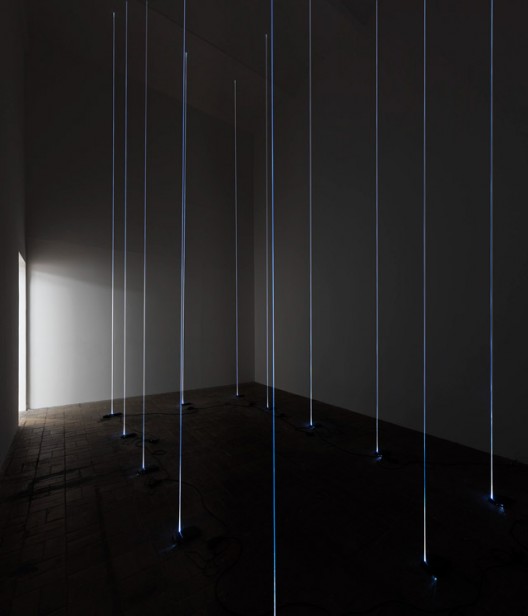

Spiros Hadjidjanos, “Network/ed Pillars”, installation view, KW institute for contemporary art Berlin, 2016.

After exchanging dozens of e-mails, notes, chats, and messages, we clamber onto Skype to talk, getting tiny glimpses, unearned portals into one another’s world. Some sit or kneel, as I do, in front of a screen in dim rooms. Some seem to be eternally lamplit in long, narrow bedrooms with high ceilings. Others work in studios with a great deal of light flooding in and where trains on a bridge are visible through the window. Still others work from school, or in city libraries, or talk to me as they walk. After our calls end, I think about them walking on through their cities. Others never get on Skype, and seem comfortable to talk only in boxes—phantoms talking about abstractions to another ghost.

There have been a thousand contemporary essays written on the irony of feeling alone and isolated despite how connected we all are, in a digital age. More interesting and rich work, for example Navneet Alang’s engagement with the archive and its hegemony, suggest how the contemporary individual, living much of her life online, is split among multiple holographic selves. Instead of finding a sense of the self that progresses over time, Alang argues, the self finds itself on hold in extended, still time; this, because every wound inflicted online is retrievable, every conversation that went awry easily revisited.

Ben Schumacher, “To be titled (boat with John Keenen)”, boat, Shrinkwrap, chair, Ikea light in original packaging, cable management unit, cables, leather, bronze cable management brackets and vinyl, dimensions variable, 2013.

This fractured self can find relief, I think, through the ritual work that goes into keeping far flung connections strong and afloat. This is work that invigorates, rather than enervates. I return to this work and seek it out because there is a special kind of happiness, pleasure, and energy in its rhythms. Briefly, I want to describe this happiness which is both a product of and endemic to how these long-distance bonds are formed and affirmed along fiber-optic cables at the bottom of the ocean.

To do so, let me return to tone; the tone that these friends and partners all share. It carries a secret, a half-formed idea that each of them is rolling around in their heads. That they even bring these personal ideas to virtual tables to talk them through is very moving to me. What seems miraculous, yet, is the degree of trust it takes to share an idea with a near-stranger they have never had a meal with. It is even more astonishing that they trust she will honor their gesture.

What is this act? Person one reaches out to person two across the Pacific because person two wrote some words on an image in a room—a painting, a collage, a sculpture. Person two found those words, knew the image being described, and the words struck a little dartboard in their heart. Again: miraculous; improbable.

Thought of this way, far from being cheap or easily found and discarded, digital exchanges seem all the more precious. They can be infused with a rare joy because they are bound by extreme and productive limits in a fraught, complicated medium.

Ben Schumacher, “Gluten and Bondage” (detail), 2014. Courtesy of The Moving Museum, Istanbul. Photo: CHROMA

Part of this joy is imaginative, if we consider the holograph a creative construct. In the absence of a friend’s body, his voice and gestures, I have to bring all the faculties of my imagination to bear, to conjure his presence, intention, and feeling. I have to imagine him, feel empathy and not lose sight of him as a human with his own struggles and disappointments in another part of the world. I have to think on my friend, meditate on her, on what makes her, her, to understand the visions she is proposing.

Just as there is a slight erotic thrill in the knowledge that my day to day, real self (though, yes, of course, the virtual self is real) is quite far from the self I project onto and through all of these screens, there is an erotic thrill in imagining the quotidian self of my friend, in the real world, thinking about what to make. My friend is bent before a screen and dreaming.

There is an even deeper happiness and joy present in the tenuous and shaky pursuit of an abstract idea with someone across the world. I find that distance forces an idea to cohere, to shed layers and harden. There are fewer bells and whistles, less possibility of subterfuge and trickery. Both sides must pull their weight, or the work will not get done. Concepts must be articulated clearly, direct to the heart. If they can’t, then they must be turned over and dissected and reformulated until they can be. I very much recognize the moment Tony Conrad describes—of confusion, awe, speechlessness, of an inability to articulate. I find I talk to faraway people who want to venture into the most thrilling, odd, and oblique territories. I think of a Paris Review piece on Chicago residents falling in love in winter, and why this love lasts: only a real feeling can provoke the effort to cross space in the most bitter, ruthless cold. In a similar fashion, only an idea that feels new and untested enough can justify all the time invested in communicating with a near-stranger. Grappling with the idea feels like love.

Spiros Hadjidjanos, “Network/ed Pillars”, installation view, KW institute for contemporary art Berlin, 2016.

Happiness is in a process that is maintained over time, guarded, cared for, and renewed. When the process starts, it is a bit like this: I heard you describe a new sensation with clarity and deep feeling. I thought of divers heading down to the bottom of the sea to repair the cables along which these bundles and packets of information are sent back and forth.

Ideas rolled across the bottom of the sea, one year, two years, three years, four; they rolled from one house to another, from my house, to yours, taking on color, substance, and form until they resembled a tangible thing. I hoped you would drag it to your house, paint and stripe it, imbue it with all your hopes, your meanings, filtered and drawn from the fictions you inhabit. You bring it back to the water to skip it back to me. The process continues until we form a wire between us, a wire that can be wrought into a net, safety, consolation. The net can be buried in the foundations of another house.

The idea is an object that we can return to again and again. This is happiness: skipping a sound across the surface of the Pacific, hoping someone will hear it on the other shore.