by Zhai Jing 翟晶

Translated by Daniel Szehin Ho

This piece is included in Ran Dian’s print magazine, issue 5 (Spring 2017)

“River of Fundament”, an operatic, five-hour-long film created by Matthew Barney in 2014, was presented in Asia for the first time last September; it is known in translation as Chongsheng zhi He— literally “River of Rebirth —which is believed to be the film’s subject.

Taking Norman Mailer’s 1983 novel Ancient Evenings as its narrative thread, the film fashions a multi-layered filmic work from the story of the protagonist’s rebirth in Mailer’s novel, the story of Osiris in Egyptian mythology, the boat crossing the river of the afterlife in the Egyptian Book of the Dead, and the historical narrative of American industrial society. The basic plot: after Norman (the protagonist of the novel, Menenhetet I, has been replaced by Norman Mailer himself in the film) dies, ceremonies of mourning are held; Norman’s deceased spirit returns home from the river of excrement, which must be traversed before reincarnation, in order to help the spirit medium Hathfertiti so that he can complete his third reincarnation. On account of Hathfertiti’s failure, the final reincarnation was a failure. Barney uses three classics from the US automotive industry—the Chrysler “Imperial” of 1967, the 1979 Pontiac “Firebird”, and the Ford “Crown Victoria Police Inceptor” of 2001—to represent the three lives of the protagonist. Amid the interchange of the three generations of automobiles, the myth of Osiris is brought in, thereby forming two parallel narratives in the film; these thread together stories of Norman and Osiris, tethering the life history of an individual to that of the American auto industry.

Due to the structure of the Egyptian myth as well as that of Mailer’s story, “rebirth” appears to underlie the work—and Barney himself, as well as his many interpreters, constantly mention rebirth while explaining the work. Yet the title “River of Fundament” reminds us that after and underlying rebirth, there seems to be something even more fundamental, and this, perhaps, is its true fundament.

The term “fundament” refers to something fundamental and basic, but also jocularly to the derrière. Some believe that this reflects the repeated scenes of anal intercourse in the novel and the film, and according to this strain, the two works are closely tied to the spiritual state of the Beat Generation and with a reality wherein homosexuality is rampant. But the core concept of the film is not homosexuality, but a river of excrement—the necessary path to rebirth—while the sexual connotations in the film are all intimately connected with the imagery of excrement. This seems to suggest that the real topic of the film is neither rebirth nor sex, but “fundament” (hence, “River of Fundament” should have been interpreted as “Jizhi zhi He”). Certainly, this is not merely an issue of translation, but involves the logic of the film and the logic and ideas underlying Barney’s art.

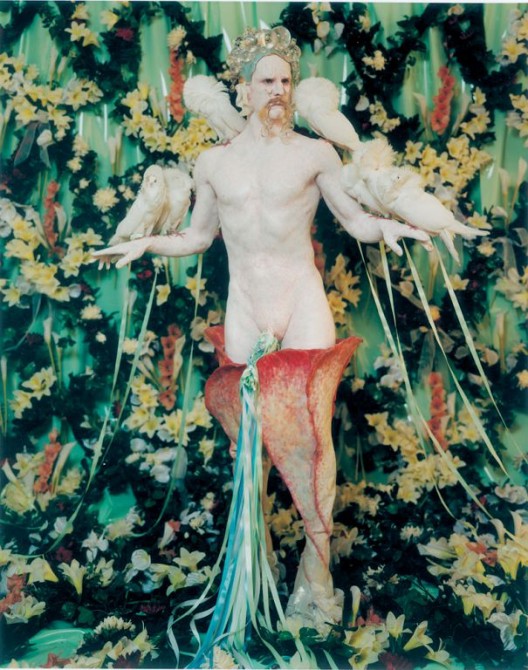

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河:REN》,剧照,2014(摄影:Kelly Thomas;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT: REN”, Production Still, 2014(Photo: Kelly Thomas, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

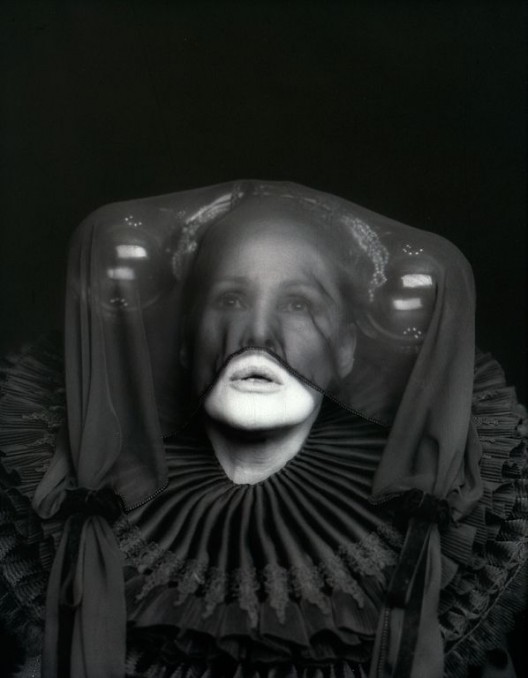

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河:REN》,剧照,2014(摄影:Ivano Grasso;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT: REN”, Production Still, 2014(Photo: Ivano Grasso, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

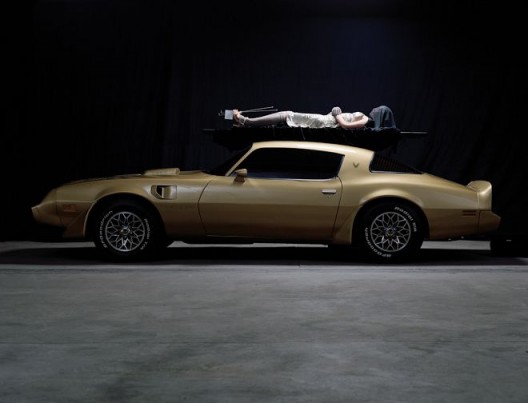

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河:REN》,剧照,2014(摄影:Chris Winget;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT: REN”, Production Still, 2014(Photo: Chris Winget, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

Fundament

When Mailer states that “Between piss and shit, we are born,” he is not only pointing at something easily observable, but also at our fundamental spiritual reality.

Shit or excrement is the most important and embarrassing form of existence in human cultural history. It lingers in a sordid place, and is itself sordid, a thing rejected and inhibited. Yet it is also a fundamental fixation of humanity. In Freud’s system, one of the earliest fixations is the fixation with feces—the anal stage. In ancient Egyptian mythology, the Pharaoh’s feces fertilizes all things, while the Egyptian god Khepri is a scarab beetle (or a dung beetle), nurturing life from excrement. On the other hand, one of the most frightful things for the ancient Egyptians was to have to eat one’s feces in the afterlife (in an inversion of the digestive system). Involuntary excretion just so happens to be what the body reverts to in moments of real fear or dizziness. This meeting of extremes has spawned a number of works that involve feces and shit in modern art.

In Barney’s film, excrement has a number of parallel meanings. When the male incarnation of Norman Mailer, Ka (one of the seven parts of the human soul, according to the ancient Egyptians) entered Mailer’s toilet at home from the river of excrement, the first thing he did was to grab a blob of feces from the toilet, wrap it in gold foil, and place it back into the toilet. Then, when Usermaatre Setenpenre (Ramesses II) appears, his penis is also wrapped in gold foil and engages in anal intercourse with Mailer; what is emitted, however, is mercury, which leaks through the crack in the door and enters into the room of Mailer’s female incarnation of Ka. The female Ka cuts open her leg, and blood gushes out. At a dizzying pace, this series of shots presents us with a few transformations of “fundament”: feces, gold, sperm, mercury, blood. We are led to understand that these concepts are not only parallel, but overlapping—one and yet plural, plural and yet one. Shit and gold: one foul excrement, the other anticipated wealth. The lowest and the most exalted—and yet the result is the same?

Whether in Barney’s film or in his diverse array of conceptual and visual resources, gold has always been exceedingly important. In Mailer’s novel, the protagonist in his first life learnt the magic of rebirth from a gold mine in the desert. In the Western River of No Return that Barney references, the gold mine is the final culmination of the plot twists; in a work by James Lee Byars appropriated by the film, Byars wears tight-fitting gold clothing; a gold Pontiac “Firebird” represents the second life of the protagonist in the film….Barney’s film was shot (and also performed on site) in three locations—Los Angeles, Detroit, and New York—hinting at the tight connection this film has with the history of wealth. This history has been etched deeply into American society and the American spirit so that it underlies an American mode of heroism. In this storyline, we see Brigham Young leading Mormons to the Great Salt Lake; we see Henry Ford, who established Detroit’s automobile empire, we see Hemingway, Norman Mailer, and Mathew Barney, as well as a large amount of Westerns, including River of No Return. Wealth is not just material existence but a spiritual dynamic that builds the identity of a people and the individual’s spiritual universe.

Many have remarked on the relationship between Barney and Wagner. The artist has continued Wagner’s ideas and realization of gesamtkunstwerk (the “total art work”); Barney’s rousing music, obscure metaphors and performances all bring Wagner to mind, and so it is not too much to say that Barney is one of the most Wagnerian artists around. Yet the resemblances between Barney and Wagner are certainly not limited to such superficial phenomena. In the second act of River of Fundament, there is a series of vast angles: the Chrysler “Imperial” that represents Osiris is cut up into fourteen pieces by Seth and jettisoned into five furnaces; the molten liquid flows out form a vast djed (the pillar-like symbol of Osiris) onto the ground. The scene reminds one of a scene from Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) where the Nibelung forge gold for the dwarf Alberich. This was no accident, as Wagner’s masterpiece has gold as a core image. Gold, a symbol of wealth, is in the opera a dynamic that enters the world, bearing power and curses, pursued by the multitude of divinities and humans. It is the land that is yearned for as well as the site of terror. Only when it returns to the dark beds of the river Rhine will the world return to peace. Revolving around this image, Wagner, with his extraordinary talents, manifests this omnipresent entanglement of love and hate in our social and spiritual history. What is yearned for is united with what is feared.

Is the feces wrapped in gold foil the symbol of this entangled love and hate? Is Barney delineating the contours of our predicament with a meaningful and symbolic juxtaposition? In Barney’s films, such juxtapositions are easily detected: the golden chamber pot of the Pharaoh, the feces-shaped (or phallic) cigar on the gold-plated crown of Horus, and so forth. Yet aside from juxtaposition, between the feces and the gold, Barney has also placed some mediums. When Usermaatre Setenpenre sodomizes Norman, the “sperm” dripping down is mercury. In alchemy (in Graeco-Roman Egypt, the Hermetica was a classic of alchemy), mercury was a fundamental substance to turn matter into gold. Barney mixes gold, sex, and bodily fluids together. In Egyptian mythology, bodily fluids are the fundamental matter with which the gods created the world. According to legend, Atum, the first god, created the first creatures by masturbating and placing the sperm in his mouth. Thus the symbol of wealth has been associated with the fundament of life, with wealth thereby entering the tracks of life; the river of fundament is also a river of wealth. It is not just a certain river in Detroit; it itself is Detroit, it is America, it is that world depicted for us by the epic, elegiac tone of Der Ring—our world. The infatuation with life is therefore the infatuation with gold; the reverse is equally true. On this level, Norman’s history of rebirth is overlaid with the social history of the United States, forming an unending thread together with ancient Egyptian mythology, alchemy, American history, Mailer’s novels, and Barney’s films. Barney’s films thus appear very classical, and yet also very contemporary.

Freud has said that a fixation with feces and with the phallus is the genesis of fetishes and all their variants. We can then also say that (Norman’s and America’s) rebirth is, in the end, a fetish.

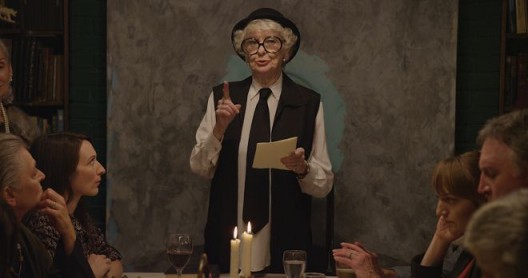

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河》,剧照,2014(摄影:Peter Strietmann;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT”, Production Still, 2014 (Cinematography: Peter Strietmann, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河:KHU》,剧照,2014(摄影:David Regen;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT: KHU”, Production Still, 2014 (Photo: David Regen, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河:KHU》,剧照,2014(摄影:Hugo Glendinning;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT: KHU”, Production Still, 2014 (Photo: Hugo Glendinning, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河:KHU》,剧照,2014(摄影:Hugo Glendinning;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT: KHU”, Production Still, 2014 (Photo: Hugo Glendinning, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

Double

The rich layers in River of Fundament originate in its multiple mythologies as well as its intellectual and visual resources. This has always been Barney’s signature, adept as he is at integrating mythologies, religions, literatures, philosophies, art histories, musical histories, historical events, and pop cultures from around the world, which also renders him an artist who is particularly complex and difficult to get to grips with. But Barney’s references are an appropriation of displacement, a process of “repetition” in the Derridean sense. We can also borrow from Artaud and call Barney’s art a type of “double.”

In River of Fundament, the story line comes from Mailer, who throughout his life had Hemingway in mind. In Barney’s film, the image of Hemingway takes a central position. There is reason to believe that, from Hemingway to Barney, there runs a line of American heroic tradition. Yet not only is Hemingway’s limpid style different from the obscurity of Mailer and Barney, the spiritual bases of the three are also utterly different. The intrepid, masculine disposition and values in Hemingway have been replaced by gloomy hesitation in Mailer. The anal elements in Mailer’s novel are not so much the product of homosexual culture as the result of skepticism; it blurs not only gender but the cognition of life and values. Precisely because of this, Hemingway’s linear narrative has become circular and cyclical—a circularity and cyclicality that is moreover obstructed and meaningless.

Meanwhile, though Barney’s work has taken up Mailer’s narrative, it is still utterly different from Mailer—differences which appear not only in the shifts in protagonists, setting, and time, among others, but also in the overall tenor of the work.

In Mailer and Barney’s stories, Hathfertiti is a key character. But while in Mailer she is a dissolute beauty, it was she who finally prevented the rebirth of Menenhetet. In Barney’s story, however, she is the conduit by which Norman gains rebirth. In ancient Egyptian mythology, she corresponds both to the goddess Hathor, who was in charge of birth, death, and the rebirth of the universe, and also to Isis. The two goddesses have elements of the cow’s head, a point elucidated by Hathfertiti wearing a cattle mask near the end of the first act, and the shot of Norman being born from the cow, slit open, in the river of feces. Finally, with her death, Norman’s rebirth fell through, but this “failure” differs from Mailer’s “obstruction.” Particularly, the obstructed cycle of life seems to have obtained a metaphorical extension at the end of the film, as Hathfertiti chants a song, the lyrics of which come from the last part of Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself”: “I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love….” One detail clearly illustrates this: in Barney’s work, Hathfertiti appears respectively as the image of childhood, youth, and old age, corresponding to Norman’s three lives in the image of youth, middle-age, and old age, and thereby playing out reincarnation as a linear narrative.

Aside from Mailer’s novel, ancient Egyptian mythology is also an important narrative thread, the most important part of which is the story of Osiris. The numerous interconnections between ancient Egyptian mythology and Christianity are already well known, and there are numerous overlapping similarities between Osiris and Christ: their identities, deaths, and resurrections, and their rule of the eternal world are similar. Attending such similarities are, of course, differences in the fundamental logic: Osiris is one god among many, while Christ represents the one and true God; Osiris continues to rule the afterworld while Christ is resurrected in the human world. Orisis’s life is cyclical, which can be seen in his identity as the god of grains as well as the cyclical movement of the vessel between his realm in the underworld and the skies above; this circularity becomes the basic tone of Egyptian mythology and social philosophy. The world of Christ, however, progresses in linear time; the linear narrative will extend to his second coming, when time itself will end.

On precisely this basis, we understand the relationship between Egypt and America, as well as Barney’s juxtaposition of the two. As the Egyptologist Geraldine Harris Pinch has noted: there is a deep connection between Egyptian mythology and the national history of America; the Washington Monument is, after all, a giant obelisk. Yet sacred Egypt is different from secular America, while ancient Egypt’s concerns about life differ from America’s concern with wealth, and the Egyptian cyclical view of time is not the same as America’s sense of time progressing. More accurately, this is not “difference” but a “repetition”—a “doubling”. It is this structure that renders rebirth as an act of fetishism and reincarnation into a linear narrative.

A key image in the film and in the novel is the best interpretation of this structure: Ka. In ancient Egyptian mythology, Ka is a person’s double; when one dies, Ka appears. But Ka has no memory of the previous life and is easily tricked. Its identity of being and yet of non-being makes it in the end a human “double.”

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河:KHU》,剧照,2014(摄影:Hugo Glendinning;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT: KHU”, Production Still, 2014 (Photo: Hugo Glendinning, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河:BA》,剧照,2014(摄影:Hugo Glendinning;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT: BA”, Production Still, 2014(Photo: Hugo Glendinning, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河:BA》,剧照,2014(摄影:Hugo Glendinning;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT: BA”, Production Still, 2014(Photo: Hugo Glendinning, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

Transformation

In the film, at that moment when the golden firebird carrying Osiris/Byars/Barney drops into the Detroit River, people recognize a glimpse of Houdini. Right from the get go, the magician has had a huge influence on Barney—playing with death and escaping from it over and over again as though being repeatedly reborn. Norman Mailer himself played Houdini in Barney’s Cremaster 2 (1999), and his appearance was foreshadowed by a poster for a Houdini performance in which the word “metamorphosis” pointed at the relationship between rebirth and metamorphosis.

The latter is a key idea in ancient Egyptian mythology, Christianity, and Barney’s system. Egyptian mythology is grounded in the transformation of life. For instance, a pharaoh was seen as Horus when alive; in death, he is seen as Osiris. Hence in the Egyptian Book of the Dead, we frequently see the dead equating themselves with all sorts of deities; this is not a metaphorical equation, but an actual “transformation”—the mutual transformation of life. People believed that the myriad of things could transform interchangeably: if one consumed the enemy’s body, his spirit would also enter one’s body and spirit. Mailer’s novel was striking in its portrayal of this idea.

Christianity also has similar characteristics. The highlight of the Catholic mass is “transubstantiation”, a belief founded on the basis of transformation in which the bread becomes the body of Christ that is then consumed by the faithful. Other examples, such as turning water into wine, the transfiguration of Christ at Mount Tabor, the conversion of St. Paul, and the rebirth of believers through baptism, among many others, share the basic idea of life’s transformation.

Destricted (2006) is a film made up of seven short films by artistic directors including Matthew Barney and Marina Abramovic. Barney’s “Hoist” sees a man supine, masturbating beneath a Caterpillar truck; his sperm is ejaculated as Vaseline which is wiped on the machine, thereby connecting life with industry. Vaseline appears frequently in Barney’s films. It is a substance that transcends boundaries, an industrial product and yet one also used to heal wounds and soothe muscles; Barney employs it repeatedly as a substance pertaining to life. Abramovic’s “Balkan Erotic Epic”, meanwhile, displays certain Balkan customs, the basic idea of which is that human sexuality (and related fundaments) can have specific effects on the external world.

From this point of entry, we understand in turn Barney’s “transformation” and his predilection for Houdini: transformation is no metaphor, but an actually-occurring metamorphosis. Thus, the automobile is not a metaphor for Osiris or Norman, but a real metamorphosis. Nor is Egyptian mythology a metaphor for the historical narrative of American industry; on the contrary, they are bound by a mysterious force, mutually transforming one another. At a dizzying rhythm, the contemporary and the ancient, life and the world, fundament and wealth are compressed into an immense primal, chaotic, muddled mass (hundun, the Daoist idea of the primal chaos full of potential, from which everything springs), as though time has reached absolute zero. Houdini, the great shape-shifter, ended up scientifically unmasking all kinds of stunt techniques. Can this passage of his be seen as a symbol of this structure?

Indeed, transformation imparts to Barney’s film its most abstruse and recondite layer. The surface level is easy to interpret (for example the frequent juxtapositions of scenes and identities, the transpositions of identities through rituals, and so on), and yet it presents an entangled, overlapping logic, constantly returning to itself and yet unfolding in a linear manner. Precisely on this basis, the ancient Egypt of constant reincarnation and the America of constant progress become an integrated whole. Yet it is a unity of “doubles”, which—perhaps—is the true structure of Barney’s “rebirth”.

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河》,剧照,2014(摄影:David Regen;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT”, Production Still, 2014(Photo: David Regen, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

马修•巴尼和Jonathan Bepler,《基质之河》,剧照,2014(摄影:David Regen;版权:马修•巴尼;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler, “RIVER OF FUNDAMENT”, Production Still, 2014(Photo: David Regen, © Matthew Barney, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.)

Modernity and Shadows

Okwui Enwezor has argued that Barney’s work extends a narrative tradition that was inaugurated with Homer’s Odyssey, an epic journey of twists and turns, and a spiritual history that is both human and social. River of Fundament is similarly a historical journey which ambles through the histories of society, literature, art, and history. Can it be regarded as an ultimate linear narrative, thus highlighting Barney’s modernist tenor?

Let us return once again to Wagner.

The Ring is Wagner’s most complex opera. Nietzsche once critiqued it as Wagner’s appeal to the “sacred;” but in Wagner, such an appeal is closely tied to doubt about the sacred. In order to safeguard justice, Wotan, the highest of the gods, created disaster; the female warrior-goddess Brünnhilde is the embodiment of truth and yet participates in the conspiracy to murder the hero Siegfried; Siegfried makes a solemn promise and yet violates his oath and dies, humiliatingly, at the hand of a coward. Finally, faced with such a confusion of sentiments, morality, and values, Wagner redeems the drama with destruction: Wotan sets the temple ablaze, Siegfried is bloodily hunted down, Brünnhilde flings herself in a sea of fire, the ring returns to the Rhine, and amid the goddess’s passionate lament, the world returns to tranquility. This opera as told by Wagner is a history of the World Spirit; it is also a history of redemption. It possesses a circular structure, and yet its circularity does not circle back on itself, but rather has no return.

And we understand Barney thus: the river of feces that Norman crosses—that silent, bubbling river of fundament—is the Detroit River, rushing forward; the circularity of life depicted in the river of feces is thus the industrial epic played out on the Detroit River. Ceaseless reincarnation and linear narrative unite as one.

Precisely because of this, we grasp the greatest difference between Barney and Mailer: with every rebirth, Menenhetet is born as an infant, while Norman, adhering to the thread of time, presents the three different periods of a life. In this symbolic manner, circularity and narrative become one. Just as the ring originates from and returns to the Rhine, it happens not as reincarnation, but in order to complete an ineluctable history. The circularity of life portrayed on the river of feces and the Detroit River is not reincarnation, but an epic that rushes headlong forward—a “river of no return”. At the end of Der Ring and at the end of River of Fundament, tragic destruction and obstruction arrive at closure through a bit of high-spirited singing that is full of hope. Hathfertiti sings Whitman’s song (“Song of Myself”), with the glory of a goddess:

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.

You will hardly know who I am or what I mean,

But I shall be good health to you nevertheless,

And filter and fibre your blood.

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop somewhere waiting for you.

In the end, what Barney recounts is not a history of rebirth but a history of redemption; this is where his fundamental similarity with Wagner lies. Precisely because of this, we can say that he is the most Wagnerian contemporary artist.

———

Zhai Jing is an associate professor of art history in the College of Fine Arts at Capital Normal University in Beijing, and works also as a supervisor of postgraduates there. She received her doctorate from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2008, and specializes in the study of postcolonial theory. The author of a number of articles, in 2013 she published A World on the Margin: On Homi K. Bhabha’s Postcolonial Theory.

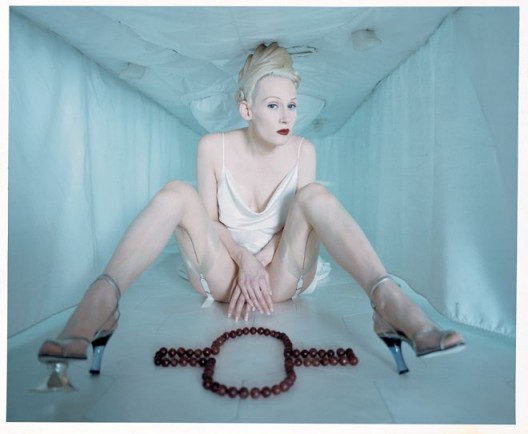

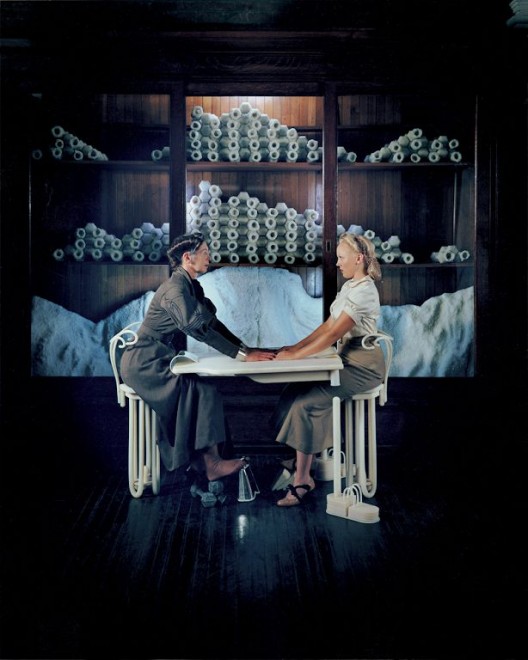

马修•巴尼,《悬丝1》,剧照,1995(摄影:Michael James O’Brien;版权:马修•巴尼1995;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney, “CREMASTER 1”, Production still, 1995(©1995 Matthew Barney, Photo: Michael James O’Brien, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels)

马修•巴尼,《悬丝1》,剧照,1995(摄影:Michael James O’Brien;版权:马修•巴尼1995;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney, “CREMASTER 1”, Production still, 1995(©1995 Matthew Barney, Photo: Michael James O’Brien, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels)

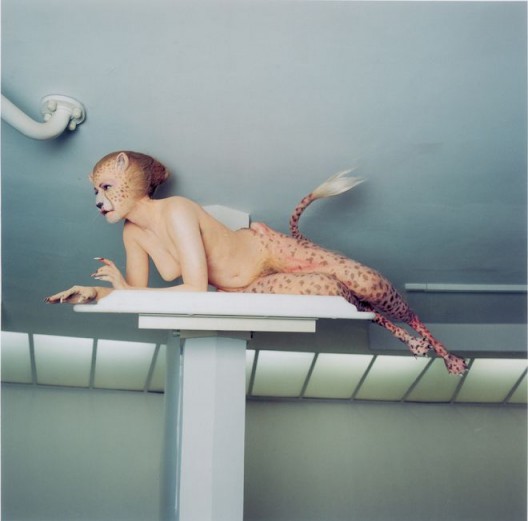

马修•巴尼,《悬丝2》,剧照,1999(摄影:Michael James O’Brien;版权:马修•巴尼1999;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney, CREMASTER 2, Production still, 1999(©1999 Matthew Barney, Photo: Chris Winget, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels)

马修•巴尼,《悬丝2》,剧照,1999(摄影:Michael James O’Brien;版权:马修•巴尼1999;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney, CREMASTER 2, Production still, 1999(©1999 Matthew Barney, Photo: Chris Winget, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels)

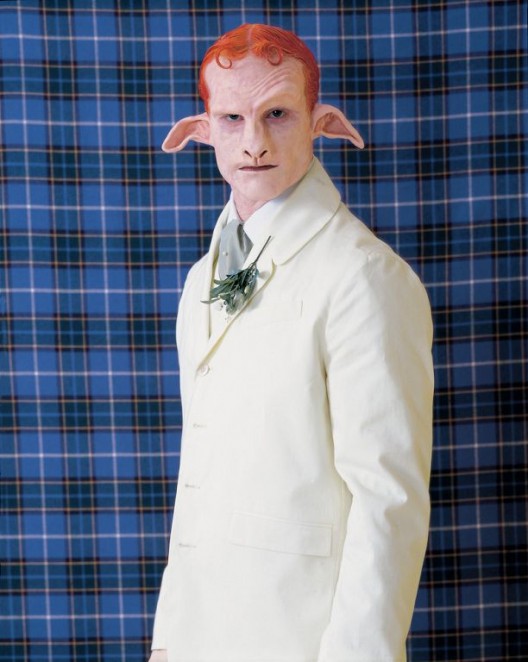

马修•巴尼,《悬丝3》,剧照,2002(摄影:Michael James O’Brien;版权:马修•巴尼2002;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney, CREMASTER 3, Production still, 2002(©2002 Matthew Barney, Photo: Chris Winget, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels)

马修•巴尼,《悬丝3》,剧照,2002(摄影:Michael James O’Brien;版权:马修•巴尼2002;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney, CREMASTER 3, Production still, 2002(©2002 Matthew Barney, Photo: Chris Winget, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels)

马修•巴尼,《悬丝4》,剧照,1994(摄影:Michael James O’Brien;版权:马修•巴尼1994;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney, CREMASTER 4, Production still, 1994(©1994 Matthew Barney, Photo: Michael James O’Brien, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels)

马修•巴尼,《悬丝4》,剧照,1994(摄影:Michael James O’Brien;版权:马修•巴尼1994;鸣谢:Gladstone Gallery/纽约/布鲁塞尔)/ Matthew Barney, CREMASTER 4, Production still, 1994(©1994 Matthew Barney, Photo: Michael James O’Brien, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels)