Gavin Turk “A” at Ben Brown Fine Art, Hong Kong

Ben Brown Fine Art (Pedder Street Hong Kong) Sept 13–Nov 15

Gavin Turk was one of the defining artists of the provocative, harum-scarum 1990s London scene, dubbed the YBAs (Young British Artists). Randian recently spoke to Turk following the opening of his first exhibition in China. Entitled simply “A”, the exhibition is a mini-retrospective and introduction to Turk’s diverse practice. Gavin Turk was born in 1967 in Guildford, England. He studied at the Royal College of Art in London and at his MA graduation exhibition in 1991 presented “Cave”, a whitewashed studio space containing only a blue English heritage plaque commemorating his presence. The College didn’t like it.

Chris Moore: Can you hear me?

Gavin Turk: Yes, I can hear you. It’s very hot here.

CM: I’m so jealous!

GT: (Laughing) It’s almost too hot!

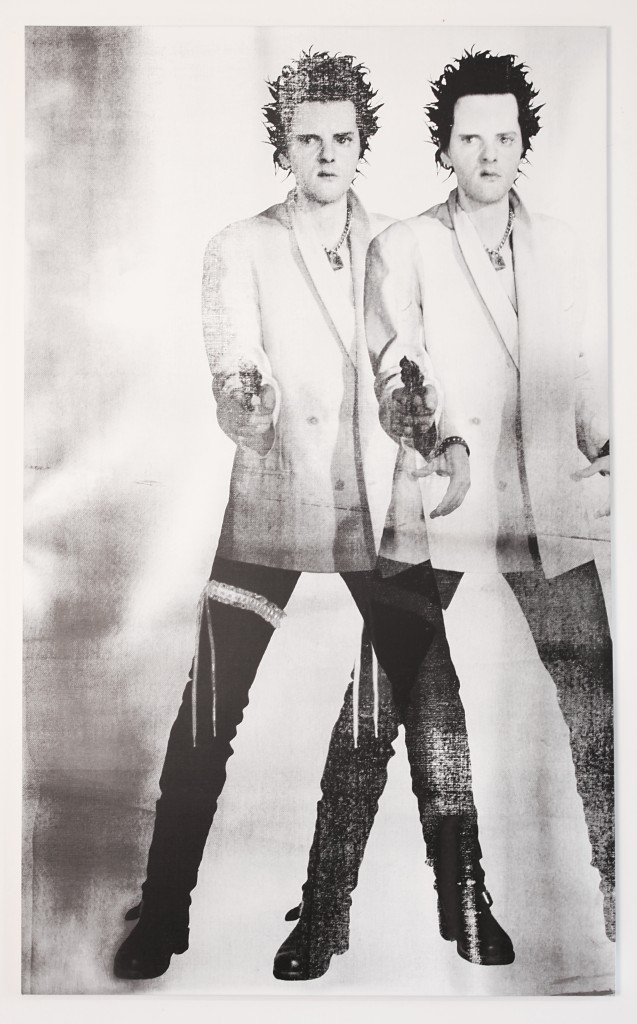

Gavin Turk, “Gunslinger”, acrylic on canvas, 225 x 135 cm; (88 5/8 x 53 1/8 in.), 2011. Copyright the Artist. Courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts, London

CM: How long have you been in Hong Kong? This is your second time in there?

GT: Third. We literally flew to Shanghai last Friday and spent a few days going to museums and openings there, and then came here at the beginning of the week; we had the opening on Tuesday night.

CM: Which do you prefer—Hong Kong or Shanghai?

GT: Ah—oh that’s a difficult question to answer. They are quite different. Obviously in Hong Kong it’s easier. I was quite surprised that Shanghai is so cosmopolitan and with what I consider to be a quite developed capitalistic depth to it, what with posters and advertising and products—it was much more liberal than we expected.

CM: Well it takes Communism to develop a really pure Capitalism. Is this your first exhibition in Asia?

GT: I had an exhibition in Seoul at Park Rui Seouk, a Korean gallery.

Gavin Turk, “Duck Rabbit (Black)”, rabbit pelt, fibreglass and wood, 90 x 120 x 90 cm; (35 3/8 x 47 1/4 x 35 3/8 in.), 2005. Copyright the Artist. Courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts, London.

CM: The trouble with looking at your work is where to begin…

GT: I tried really hard to present something that could cover a few bases and consider a wider range of art rather than just throw the audience into a current project where everything has one sense to it, like an installation, to show something with a slightly retrospective feel. There are some older works in it. There’s one piece, a neon sculpture, from 1994. I thought it was important to make some sort of an introduction to the audience here.

CM: Looking at the span of your work, and looking at things like Post-Modernism now—just a continuation of Modernism by other means, where so much of your work is about recycling, whether images or litter— what is innovation now? Is it possible to innovate any more?

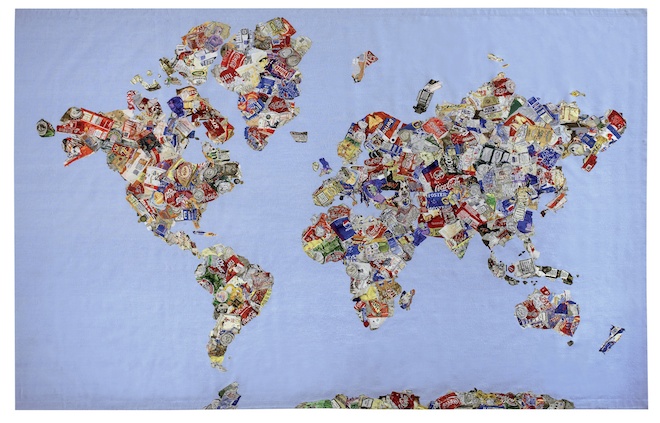

GT: Well I was trying to think about this, this sense of ‘superseding’ or the idea of art history—of the way we understand art history—in a canonical fashion, with every generation producing a greater, better and more relevant artist for that period. I think if my art is to be subjected to [the art of ] other people, to be ransomed to art history, looking into how other artists think and work, to deal with how my art is always in service to other people’s art, I think it is probably the space that I want to occupy, the space between these artists, or the space created when you mix up strange bedfellows, when you mix up quotations and ideas and thoughts and contemporary packaging, when you mix up logos of products on the street today, when you mix those up with an idea that comes from an artist working at the turn of the century—how that functions. I guess we’re trying to approach the matter sideways.

CM: Obviously in your work artists and their work are media, but also the movements themselves —so Pop and Conceptualism are also just media.

GT: I try to think of formal and intellectual relationships to art. And also formal relationships to things that exist in the world and the technology required to make those things, and also to the intellectual investment in those modern things that we have around us. The art I make is fairly conventional. I mean that in the sense that, for instance, at the moment I don’t do that much work that involves electricity [laughing], except perhaps neon lights, but neon is already a dated material. It has a history inherent in it, whereas now a lot of people are moving into LED, for instance.

CM: I’m also thinking of the merging of different things, such as your double portrait series, “Gunslinger”, which combines Warhol and Sid Vicious, a melding of Punk and Pop.

GT: It is a much more recent image than the sculpture I made back in ‘93 which was a waxwork sculpture of me as Sid Vicious. In 2004 I photographed it and turned it into this very Warhol-style screen-printed image. So it was a strange appropriation of my own history as well, using other artists to do it.

Gavin Turk “Mappa del Mundo” 2008. © the Artist, Courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts (note the refernce to Vito Acconci).

CM: Does that mean Punk and Pop are eating themselves?

GT: Probably—and art! Maybe it already did and we’re picking through the bits that came out the other end! (Laughing).

CM: You can see where I am moving to with all of this. You also made the wax sculpture of yourself as David’s Marat. There are a number of different starts to Modernism, but we can look at that painting and say that it is probably one of them. And here it is turned into something like a Catholic icon of martyrdom. And at the same time Modernism is also about death, in the sense of a disruption, a revolution, transforming and destructive. And now Modernism seems to be coming to some kind of endpoint—albeit a very long, drawn-out one!—and I am wondering, what happens with this role of disruption—can art still be disruptive?

GT: For me the role of the artist isn’t entirely to be disruptive. It is a simple musing or poetic form. Rather than simply being a reflection of death it can be a musing on that process. The notion of postmodernism—and it’s quite interesting to still be able to use the term because all too often we are trying to get rid of it or we don’t know what to do now that we have chucked modernism away, and we have got postmodernism— seems to have been wholly focused on this idea of the end of art and the death of art. But having said that, there doesn’t seem to be any kind of alternative. We’re stuck in a cycle or a loop. I don’t necessarily think it’s a bad thing. Obviously for art there is still a process of trying to question ideas of reality. I like to think art can question people’s preconceptions, the notions that people have about art which died there. But actually the preconception itself was conceived on uncertain footing, somehow misguided.

Maybe this disruption you mentioned before is the attempt to try and dislodge some preconceptions that are unfounded.

CM: Does it succeed or—?

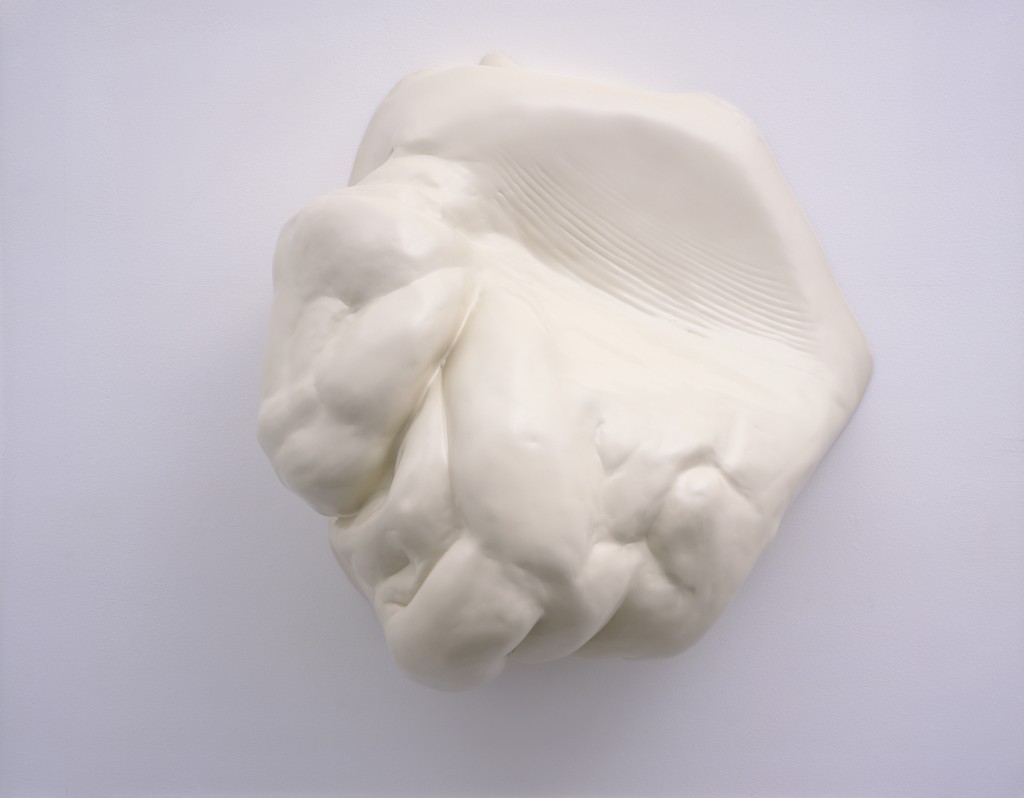

Gavin Turk, “PK2″, painted fibreglass, 58 x 50 x 26 cm; (22 7/8 x 19 3/4 x 10 1/4 in.), 1998. Copyright the Artist. Courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts, London

GT: (Laughing) Well, sometimes it has a good go at it! Others possibly not. But there’s no harm in trying.

CM: Sorry, it’s an impossible question to answer.

GT: But it’s still a question that continually needs to be asked. It’s similar to the question, who is the audience? It guides the process and it leaves these unanswerable questions. It is the engine that keeps art plodding along.

CM: Are there limits to this conversation?

GT: Often as you attempt to dislodge a preconception, you may replace it with another, which is also not entirely correct. I think that as art is seen through different filters, cultural contexts, economic contexts, time frame contexts, art does shift and change and the philosophies that are inherent to the art of the time change and people come to art and look at art in different ways. They have a kind of use, of art for that specific local point in time and space when they come into contact with it.

CM: Speaking of cultural and economic contexts, there are certain threads that can apply universally, one of which you pick up on is the rubbish that is expelled by people, such as polystyrene, [note a further Punk connection here: Poly Styrene, the singer] an object that is mainly air and the moment it is produced, it is already degrading relatively quickly. And you have used different sorts, such as burger packets.

GT: Originally, the uses of polystyrene for me were twofold. The first use was teacups—something quintessentially British to do is to drink tea from a polystyrene cup, so you could take it outside. My conceit was to suggest we take it outside to look at the English landscape, which is a culturally defining moment, as we can see from Constable, Turner, Henry Moore and John Ruskin’s romantic idea of the English countryside. So this polystyrene cup of wasted tea was a cultural distillate. Similarly there was a little plate—a little tray—another cultural cliché that [suggests] everyone in the UK wanders around eating fish and chips the whole time. Also I wanted to cast it into bronze and then paint it, and polystyrene can be invested straight away and then be burnt out and replaced with bronze, so you can use “lost polystyrene” process of casting, and get really high, wonderful detail, with all the little grains. You can’t see it’s a painting—a trompe l’oeil, a deception, something that isn’t what you think it is. Or, to put it another way, it is what you think it is until you know it isn’t what you thought it was. But it is also still what you thought it was. And in the exhibition here I have a polystyrene boxes that you find in the markets here.

Someone at the opening asked me “why is the box you made iconic?” And I thought, no, it’s not iconic—the box before was iconic!

Gavin Turk, “Port (Yellow)”, neon, 216 x 100 x 6 cm; (85 1/8 x 39 3/8 x 2 3/8 in.), 2012. Copyright the Artist. Courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts, London

CM: You’re exploiting the icon.

GT: Yes and also my own history, in relation to my own work. I am trying to expose the audience to the idea that art is simply cultural redistribution, something that exposes the side of us that is cultural rather than personal—the bit of us that is us as opposed to that which is made around us.

CM: Were you at all inspired by Méret Oppenheim’s “Object”, the fur teacup? (1)

GT: I love that piece! Yes, I am totally inspired by her. She is a very interesting artist, an artist who made a few works that have immediately struck really deep. There’s this thing about being uncanny, about being unnerved, something you know and something you obviously don’t know rising at exactly the same moment, which I think is really the definition of surrealism.

CM: I guess this is what I was getting at with regard to disruption, because you use surrealism quite a lot in your work. I was looking at your polished clay heads and also these takes on Magritte, who was trying to make something uncanny, unworldly. (2) So art that was uncanny already, you’ve recycled its uncanny-ness.

GT: [Laughing] Hopefully! I quite like that—I don’t mind saying that is something that I like!

CM: The final question I would like to ask is, looking at the polystyrene box—it’s a fake box and a camouflage box, and you also take on Andy Warhol’s idea of camouflage as well—looking at paint as camouflage, at paint as something to hide behind, looking at identity. An ongoing theme in your work is self-portraiture —although not to make self-portraits, but to undermine them.

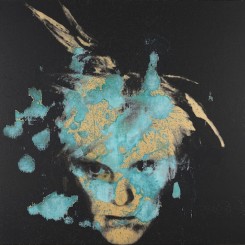

GT: I might make a work that has my face in it. I’m simultaneously talking about portraiture in art and a series of art works that return the audience to the philosophical concepts of art, we can call it modernism or postmodernism, so all art is a process of self-portraiture. My image is used then as ‘Not-a-Warhol’, but also as ‘Not-me’. Quite often people mistake this. People say I want to be Andy Warhol, simply putting myself in place of Andy Warhol. And this closes everything down. The question about Andy Warhol is not so straightforward as whether one can be Andy Warhol. I can’t replace something with me. I’m not sure what “me” is—“me” is using mixed identity. This is not being me.

* This interview took place by telephone on September 25, 2014.

Notes

1. Méret Oppenheim (Swiss, 1913–1985) “Object” Paris, 1936. a teacup and saucer with teaspoon all covered with the fur of a Chinese gazelle.

2. for example, “Godot’s day off” and “Cripple” 1999.