It is more or less generally accepted that the earliest surviving examples of traditional Chinese engravings—woodblock prints illustrating scenes from the Diamond Sutra—were found in the Dunhuang Grottoes and date back to 868 AD (the ninth year of Xiantong). During the Song and Yuan Dynasties, the development of printmaking techniques led to the more widespread application of prints, and greater innovations on traditional printmaking began to arise. Ming Dynasty painters such as Qiu Ying and Tang Yin were known to have sometimes employed printmaking as a drafting technique, while Chen Hongshou’s “Bogut Leaves” and “Leaves of Water Margin”, along with Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden (printed during the reign of the Kangxi emperor in the Qing Dynasty) are even more commonly mentioned as examples of traditional Chinese printmaking.

However, “creative printmaking” as such—or rather printmaking since the advent of the modern era—has not been entirely successful in shaking itself off from the tradition of ancient Chinese printmaking. Lu Xun once said, “To date, Chinese printmaking techniques have yet to be refined. Rather than attempting to disguise their work as something new, artists should consider a more measured progression”. From the 1920s onwards, Lu Xun began publishing collections of a number of foreign prints, and founding a printmaking training institute. In Lu Xun and the One Eight Society, the printmaker Jiang Fengzeng reminisces, “After we saw Meffert’s ‘Cement Series’ which Lu Xun had published at his own expense, it was like a whole world opened up for us…from then on, we decided to forsake oil painting for printmaking.”[1] Quite a few young artists working in the medium drew inspiration from Western printmakers; these qualities of open mindedness and innovation are virtually the birthright of the medium, giving printmaking its own place in China’s modern art history.

Sifang Studio was founded in Beijing in 1997. Following the avant-garde art movement and the influx of the market economy, art in China was undergoing a transition which involved clashes between the local traditional culture and modern Western culture. In the 1980s, printmaking broke away from the strong political overtones of the past and shifted towards dealing with material, texture, and technique. However, this put the medium at risk of detachment from reality. From this perspective, the original intent of Sifang Studio’s founding was to seek out an avenue for the rather isolated medium to break through into the common discourse. The four young instructors from China Central Academy of Fine Arts were keenly aware of the anxieties facing the development of printmaking. Young and in their prime, the four were brought together by their desire to change what they saw as an unsatisfactory status quo; they attempted to explore the variability of the medium’s language and engage in more socially and conceptually driven modes of expression.

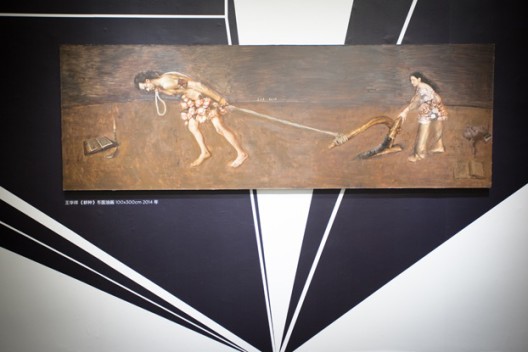

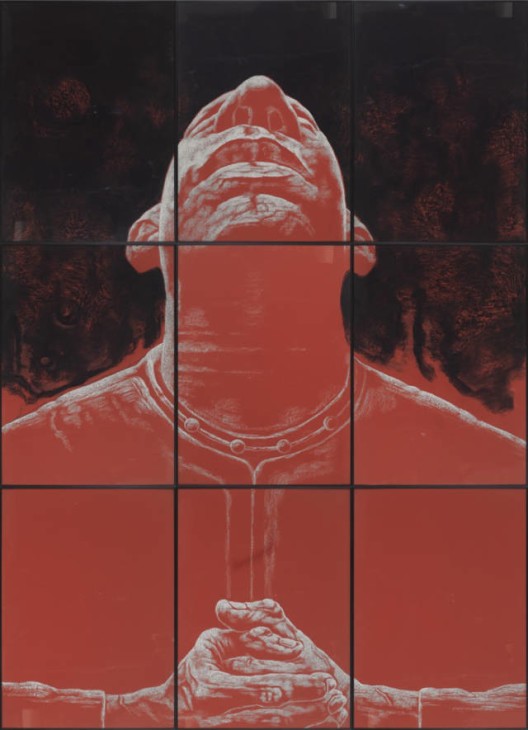

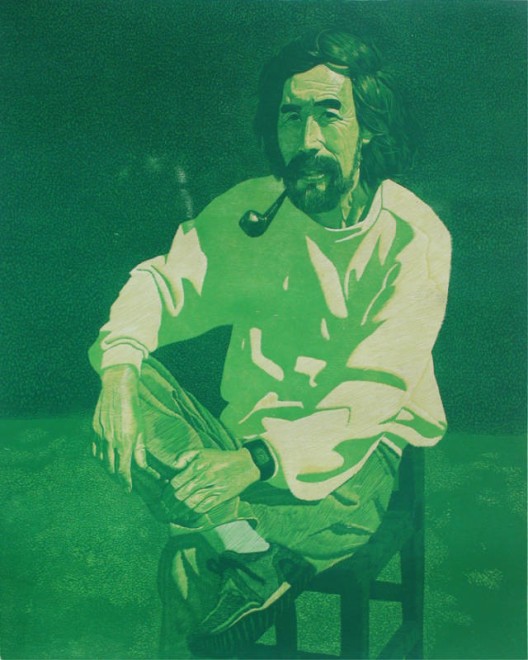

In contrast with the idea of a traditional studio, Sifang Studio was rather more flexible as an organization. Its relaxed and inclusive approach to form gave its members a greater sense of autonomy and independence, and because the studio acted as a mouthpiece to the public, its members’ opinions were all the more influential. The four members of the studio—Su Xinping, Tan Ping, Wang Huaxiang and Zhou Jirong—each come from different printmaking backgrounds (lithography, etching, wood and screen-printing, respectively). Each member’s use of tools, materials, and technique is clearly distinct from the others, and in a way, these distinctions represent the open-mindedness and inclusiveness of Sifang Studio—which also coincides with the inherently liberal spirit of printmaking itself. While devoting themselves to exploring and creating their own artistic languages, the four studio members also experimented with integrated materials, dabbling in other artistic domains. Su Xinping and Wang Huaxiang have even expanded their artistic practice to oil painting.

In May 1998, Sifang Studio held its first exhibition in Beijing, and invited a number of critics and artists from China and abroad to take part in their “Chinese Art in Transition” forum. Although this forum was based on the four’s printmaking work, its intention was very clear: it was meant to “lead into a discussion of more large-scale issues—issues existing within contemporary Chinese art such as ‘Chinese art in transition’ and ‘The transformation of Chinese art.’” [2] The openness of this mindset demonstrated that the four artists were not academics, despite their orthodox fine arts academy backgrounds. They were attempting to create change within the system of art academies. Whether or not their forum would truly improve the plight of Chinese printmaking or even “transform” Chinese art was yet to be seen, but the attempt in itself was positive and meaningful. It was this openness and overarching perspective that broadened Sifang’s horizons, helping the studio discover room for growth.

Those four ambitious young print makers back then now have the full strength of the academy behind them, and each has come to represent a different type of printmaking. Painted on the floor in the center of the exhibition hall is a large cross, with “Sifang Studio” written at its intersection. The four points of the cross point towards the four walls of the exhibition space. Large projections forge a strong visual impact, and the artists’ works hang at the center of the projections. Initially, this arrangement appears ingenious and convincing, but it is in fact more form than content. Sifang Studio member Wang Huaxiang once said during the “China Art in Transition” forum: “An artist’s work is spiritual; it is without beginning and without end. This, I feel, is the most important process.” Sifang Studio is not the place where artistic creation originates; instead, it was meant to nurture this type of artistic spirit. The curator has attempted to show how the language of these artists’ works have developed over time, but unfortunately, the works and documents displayed high up on the walls of the space do not appear to be in any recognizable order. It is impossible to discover any sort of adherence to the so-called concept of “four artists showing four types of printmaking”. Meanwhile, the viewing angle has purposely been set higher than usual, which cuts off the interaction between the viewer and the pieces on show, so the “open” concept of the square becomes conversely enclosed. Inside this boxed in space, the artists’ pieces are no longer meant to be viewed, but rather gazed upon in reverence.

The works on show (Four Reasons of Each Artist Exhibiting the Painting: Art Language’s Development of Sifang Studio’s Artists) had been arranged entirely according to each of the artists’ positions within the academy system. Works by Tan Ping, the former vice-president of CAFA, and Su Xinping, the current vice president of CAFA, have been placed on the two walls directly facing the entrance to the exhibition hall; Tan Ping, moreover, also spoke as the representative of Sifang Studio at the exhibition’s opening ceremony. Interestingly enough, the curator of this exhibition was also a CAFA professor with an academy background, while many in the audience at the opening ceremony also happened to be students of the four artists. Clearly, the exhibition space was the academic system in miniature—a decisive victory for printmaking within the academy. The show itself, too, in the end seemed a fantastic opportunity for the art and the academic systems to draw more intimately to one another and revel in the intoxication of their triumph.

[1] Li Hua, Liu Shusheng, Ma Ke ed. Fifty Years of China’s Emerging Printmaking Movement 1931 – 1981, Shenyang: Liaoning Fine Arts Publishing Company, August, 1982, page 188 李桦、李树声、马克 编:《中国新兴版画运动五十年1931-1981》,沈阳:辽宁美术出版社,1982年8月,第188页;

[2] Chinese Printmaking Vol. 14, Beijing, People’s Fine Arts Publishing House. December, 1999. Page 62. 《中国版画》编辑部编辑:《中国版画 第14期》,北京:人民美术出版社,1999年12月,第62页.