Contemporary Collector, Modern Philanthropist

By Chris Moore

Simon Mordant is one of Australia’s most prolific art collectors and philanthropists. As chair of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney and as Australia’s past Venice Biennale Pavilion Commissioner, Mordant has been one of the major forces driving modernization of Australia’s visual arts scene. Simon and his wife, Catriona, live in Sydney. Chris Moore spoke with Simon via video conference during the Covid19 lockdown.

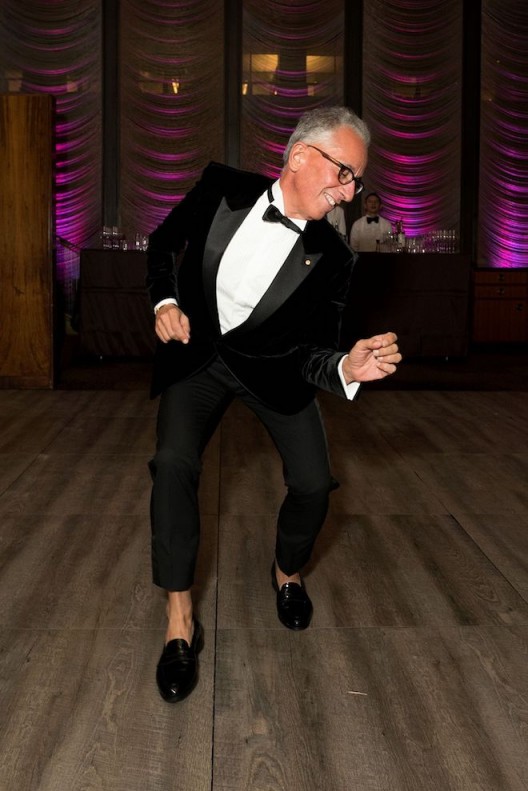

Simon Mordant is sitting in his office at his beach house. He is thoughtful in his responses but also fairly relaxed, defensive only when criticisms of Australia are raised regarding his adopted country (his voice has also adopted some monotone Australian drawl). Born in 1959 in England, aged 23 Mordant emigrated in 1983 to Australia. Since then Mordant has become the picture of the browned, successful Aussie. In 2010 he and Catriona donated AUD 15 million (at the time, around USD 12 million) towards the AUD 53 million redevelopment of the Museum of Contemporary Art, and in doing so also brought State and Federal governments to each contribute AUD13 million too. In 2012, Mordant was awarded Member of the Order of Australia for services to the arts and cultural community. In 2020 he was knighted in Italy. This week Simon was awarded Officer of the Order of Australia, the country’s second highest honor, for services to the visual arts. We begin our conversation with the question of why he became an art collector.

“We’ve never thought of it as collecting. We love being around creative people, whether that’s visual artists or performing artists. We enjoy being around people making excellent things, and along the journey we’ve been able to acquire works that hit us emotionally in the heart and are works that we’ve loved at the time that we bought them. We’ve never sold anything that we bought. There are a number of works that we’ve acquired over 35 years, and some no longer have that same emotional response. So, we don’t show those works in our homes or offices, and increasingly works that we know we’re not going to show, we’re gifting to public institutions, rather than have them gathering dust in a warehouse. But every single thing we’ve bought has had an emotional impact on us at the time of purchase. And in pretty much every case we’ve got to know the artist or maker subsequently, and in some cases, we’ve supported the artist for 30 years and in some cases have 30 or 40 works by that artist over their particular career.”

The Hangman’s House

I ask whether there are particular art works that have maintained their interest over a long period of time? “I still have on my desk in the city the first work of art that I bought. When I was 22, I wandered into the Royal Academy Summer Show and saw this work in my lunch hour. It had a really significant personal impact. It was a picture of a house in a field of flowers. It was unusually beautiful, but it had a very odd title. The work was called “The Hangman’s House”. I couldn’t reconcile the beauty of the picture to the title. I wrote to the artist and asked her to explain to me the context of the picture. The artist wrote back and her letter is stuck on the back of the picture and that picture sits on my desk and I look at it every day.

“We often open our homes to international museums and collectors who are visiting. Often people will ask us, in the event of a fire, what would you take? We always answer the same way: there are some sculptures that our son made at kindergarten, when he was 4 or 5 years old, and they would be the things that we would grab in the event of a fire.”

‘The Hangman’s House’ was the first artwork you bought. How did it develop from there? “I continued to buy works that I loved, that were beautiful, that had an impact on me through my early 20s. And then I chose to emigrate to Australia by myself, left my family, and came to Australia with maybe 8 or 10 pictures that I’d bought and some clothes. What I quickly realized was that for whatever reasons, those artworks didn’t work in Australia. The light was different. My state of mind was different. They no longer resonated with me. I started to learn a little about Australian contemporary art. There were no museums dedicated to contemporary art when I arrived, and the state-owned institutions were full of dead art and were very unchallenging for me. I mean, I love van Gogh and Renoir, but I can’t sit down and talk to them about what was on their mind when they were creating a particular work. I can read books or letters or correspondence but with a living artist, you can sit down and have a discussion with them about what was on their mind. So, I quickly gyrated towards contemporary art and started to learn about Australian contemporary art, and visited galleries and institutions, and then started to collect Australian contemporary art.”

Leaving England

What prompted you to move to Australia?

“In 1977, when I finished school in England, Margaret Thatcher had just been elected Prime Minister after a long period of Labour governments. The country was under general strike. The IRA were very prevalent. I can remember my father looking under his car every day before he went to work in case there was a bomb. [a common practice for business people at the time] My best friend at school’s father was killed by the IRA. I was in Harrods when the bomb went off. I was pretty disillusioned with England. I didn’t like the class structure. There was no meritocracy. I felt I needed to go somewhere that spoke English, because I didn’t have other languages. And I needed to go somewhere that my family had never been before, to be able to prove to myself that I could make a go of something myself.

“I decided to travel over land and see how far I could go. I’d never been out of Europe before. I had no idea where I would get to. Australia was my target, but I didn’t know if I was going to be able to get there or not. This was my gap year [between school and university]. I’d failed an audition for the National Youth Theatre in England, which I’d set my heart on. So, I was pretty disillusioned and set out on this journey of discovery by myself as a 17-year-old and eventually got to Australia. I met a lot of Australians who were travelling the other way. By the time I got to Australia, a lot of those people were back home, and I felt really comfortable and settled. I then tried to emigrate. Unfortunately, I didn’t have any qualifications for that time and therefore was not able to emigrate. Very reluctantly I went back to London in 1978 and in 1983 qualified as a chartered accountant, with the sole purpose of getting that qualification in order to emigrate, which I did as soon as I qualified. I emigrated in 1983.“At the time I emigrated, my parents thought they’d wasted their money on my education. They’d made significant sacrifices to put me and my brother through boarding school. I was the eldest of two and I shot through as soon as I finished school and never really lived at home, because I was at boarding school from the age of 7. My brother went to boarding school at the age of 6. He had a similar reaction, albeit a little after me; he moved to South America and subsequently, about 25 years ago, settled in Bali, where he [has] lived ever since.” – I remark these are examples of successful education. “Subsequently my father apologized for criticizing the decision to emigrate and my parents loved coming to Australia. They came for a couple of months each year, and my father came here to die 16 years ago, and he’s now scattered off our jetty. They fell in love with the place subsequently, before I emigrated they had a very 1950s perception of what Australia was…until they got here and saw it for themselves, they didn’t understand why I had chosen to move here.”

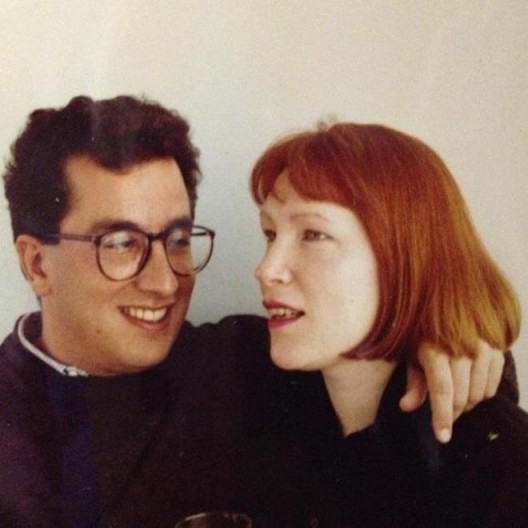

Catriona

You moved to Australia and started working as an Chartered Accountant. “Yeah, I didn’t really last long as a chartered accountant. I used that to get my emigration and sponsorship by an employer. Within 6 months I’d left the profession and moved into investment banking, then in its relative infancy in Australia. This was early 1984. Every summer in Australia there’s something called the Sydney Festival for the month of January. There’s a lot of art and public performances. Every year I used to go to Opera in the Park, which was a free opera for about a hundred thousand people in the Domain [a park in central Sydney]. I used to get there early and take a big picnic rug and friends would come and join me through the day until the opera performance in the evening. In the summer of 1988 one of the people that was joining me was a very dear friend, who was a single mum. I was an early adopter of technology, so I had one of those military-style mobile phones, with the handset sort of glued to a car-battery, with a 6-foot aerial. I was sitting down in the park and the phone rang. It was this friend to say that her young daughter was sick, and she couldn’t come but she had planned to bring a friend and she was going to come anyway, and where was I located so she could find me. I said, ‘Of course! There’s going to be about 20 of us here… I was wondering back to my car to get another Esky [cooler box] of beer and wine, and I recognized this person who’d been described to me. We went back to the picnic. We talked all the way through the opera and subsequently arranged to meet for dinner together. We were married six weeks after that dinner.

“Catriona grew up in the theater. So, she had been surrounded by creative people. Her mother was a dancer. Together we had a shared creative interest. She had some art works artists had given her in return for staying in her apartment or just gifts from friendships. We started this journey together. It started as a hobby, it became a passion, and then it moved into an obsession.”

At this point it is hard to tell whether Mordant is talking about art collecting or Catriona. Possibly both.

“For the last 30-plus years we’ve been on this journey together, which we’ve absolutely loved. Because we travel a huge amount, we’ve seen art in many different places. We generally find that places going through significant change are producing the most interesting art. Whether it’s the Middle East, or Korea – given the tensions between North and South or Africa, we find that art coming from places going through change is more impactful upon us. In more recent years, the relatively safe economies of Australia and North America aren’t producing work that has the same level of emotional impact on us. Maybe post Covid this will change. Yes, we have continued to buy Australian and North American art, but our main focus is on markets going through significant change.”

***

The conversation moves on to how Simon began to be involved in the Australian art scene. “In 1983 there was no institution focused on contemporary art. The state museums had eclectic collections, mostly of dead artists, a lot of colonial Australian art – interesting but certainly not emotionally appealing. So, I started to ask around: where were the commercial galleries? But there weren’t many commercial galleries in Sydney then. I started to meet the gallerists and go to openings. If I saw something I liked and I could afford it, I’d buy it. I then heard – this must have been the mid-80s – that there was an initiative to start a museum of contemporary art. A guy called John Power (1881-1943, an Australian artist) had died at the end of the Second World War and he’d left a bequest […in which] he had stipulated,

“…to make available to the people of Australia the latest ideas and theories…of the most recent contemporary art of the world and by creation of schools, lecture halls, museums and other places for the purpose…of suitably housing the works purchased so as to bring the people of Australia in more direct touch with the latest art developments in other countries.”

That bequest had been left to Sydney University, who had not completely fulfilled the terms of the bequest as there was no museum. A few people unearthed this bequest and put the university under some pressure to meet the obligations that had been stipulated. I became quite close to Leon Paroissien, who was driving that initiative and who subsequently became the first director of the Museum of Contemporary Art when it opened in 1991.(1) I can remember in the late 80s going through this shell of a building with my wife, looking at this ambitious desire to turn a building on Circular Quay into a museum. I joined the inaugural board of the foundation of the museum, and subsequently in the mid-90s joined the Board of the museum and chaired the finance committee. At that point the museum was in significant financial strife. Annual attendance was under 100,000 people and the institution was close to bankrupt. Bernice Murphy, the second director of the museum had resigned. A search was begun for her successor. I was in London on business and I met with a short list of candidates to potentially succeed Bernice. I met Liz Ann Macgregor and realized that she was going to be the most outstanding director, and I wasn’t going to leave the room until she had agreed to take the job. She came out in 1999 as the third director of the museum and very quickly transformed it.

“She lifted the admission charge, which, given it was our key source of income, was a pretty brave move… for an institution that was effectively bankrupt. She found a sponsor, Telstra, who was prepared to give the funds for free admission, and over the next 15 years the audience grew exponentially to 500,000 people. In that period, Board chair, David Coe and his wife and Cartriona and I supported the museum buying Australian contemporary art. In 2008, I recognized that the place was bursting at the seams and, in the absence of change, we were going to lose Liz Ann, because she was not being challenged and had taken the place as far as she could. I proposed re-establishing a foundation to raise money to redevelop the institution. The museum had a vacant carpark on the northern end of the building at Circular Quay and with architect Sam Marshall we came up with a design concept that would solve many of the issues that we faced.”

The first firm to win an architectural competition regarding the MCA was Tokyo’s SANAA in 1997. The project to add a cinematheque was ultimately abandoned (SANAA’s Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa subsequently won another competition to design the Sydney Modern annex to the Art Gallery of New South Wales). Another competition held in 2001 by the City of Sydney was won by Berlin firm Sauerbruch & Hutton, first for an annex to the existing building and then for an expanded concept replacing the old building, and again including a cinema complex. But Sydney has seen many notable old buildings obliterated, particularly on Circular Quay, so there was great public outcry at the risk to a relatively bland 1930s Art Deco sandstone building being destroyed. Plans to expand the museum were abandoned. (2)

Like many cultural architecture projects in Sydney whose designs are drawn from competitions (most infamously, Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House), Sydney Modern is also controversial, with an construction budget of AUD 450 reduced in 2017 to AUD 344, necessitating a substantial redesign, which ultimately also caused the construction contractor to withdraw. Former Australian Prime Minister and art collector, Paul Keating, who frequently comments on urban planning, described the Sydney Modern plan as a “swollen lump of [a] megaplex on the bridge across the expressway.” (3) Frankly, getting any cultural building off the ground in Sydney is extraordinary, however ill suited.

The discussion with Mordant continues. By late 2008 the MCA building’s problems were becoming acute. “We decided to design something that would solve our problems. Firstly, circulation. Secondly, creating a world-class education center. Thirdly, improving the gallery spaces. Fourthly, making the building more welcoming. The existing building was…quite an austere building, so the extension needed to ‘smell’ of ‘contemporary’. And finally, to create spaces to enable the institution to be financially sustainable. We built two massive rooftop function spaces, which have been the most popular venue spaces in Australia, for weddings and corporate events and there are also office tenancies. We included a couple of cafes and bookshop, which also created significant income. We then went out and started to fund raise for that in 2010. With Liz Ann I led that campaign.” This was the same year Simon was appointed Chair of the MCA Foundation. “The GFC hit [the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-08] when we were halfway through, which caused obviously a significant headache, but ultimately the building opened in 2012, on time and within budget, and since […then] visitors have exceeded a million a year. Last year we were announced as the most visited contemporary art museum in the world.” The Art Newspaper reported that the MCA beat other renowned institutions such as the UCCA in Beijing (905,000), the Serpentine in London (770,000), and the New Museum in New York, the MCA Chicago, and the Hammer and MoCA in Los Angeles, all three of which had fewer than 350,000 visitors each in 2018. (4) As Simon says, “which was completely extraordinary for a city the size of Sydney.” (Mordant’s comment is true but it no doubt helps that Circular Quay is the most visited tourist destination in Australia, although 60 percent of the MCA’s visitors are locals, not tourists).

Simon Mordant with Malcolm Turnbull, Prime Minister of Australia, Lucy Turnbull, and Elizabeth Ann Macgregor (photo Anna Kučera)

“Now we’re closed because of the Covid situation [MCA reopens on June 16]. We’re fortunate that we’ve built a prudent level of reserves to help weather the storm. And the storm’s been fierce, because all our function revenue [events] evaporated.” Projected revenue for the museum dropped from 22 million to 13 million. “We’ve had to dramatically reshape the place during this period of closure and that coincides with my 10 years as Chair of the Board, finishing in July. Last week we announced my successor from amongst the board members.” Lorraine Tarabay, the new Chair, is also a collector and former investment banker, whom Simon has known for almost half her life.

The Tate

I ask Simon about how the Australian art scene has changed in the last 20-30 years and mention my personal feeling that the visual arts still lag behind other areas of Australian cultural endeavor, such as film and music. In my view there are reasons for this situation. Australia is isolated compared to Europe or America but it is very wealthy, well-educated, well-travelled, extremely multi-cultural, so we have connections everywhere, not least of all to our neighbors in South East and East Asia, including China, Indonesia, Japan and South Korea, each amongst the most influential countries in the international art world. Does Australia do enough to take advantage of that more than superficially? “I’m not sure you’re entirely correct. I think part of the problem is the perception that Australia’s a very long way away. Therefore, curators in Europe and North America, who are reluctant to spend 24 hours on an aeroplane, would rather go to things that are more familiar to them. But when they come here, and then go on artist studio visits, and meet artists, and see collections, they come away completely inspired and recognize that they made a mistake by not having invested the time before.

One of the things I am most proud of is an initiative that the MCA entered into with the Tate in London 5 years ago. Qantas (the Australian national airline) was winding up its foundation and was looking for a way to increase the profile of Australian artists internationally with the remainder of the funds, which came from selling its collection. I was concerned that institutions like the Tate had very little Australian art in their collections. With Liz Ann Macgregor we commenced a discussion with the Tate about a joint acquisition program. There’s never been a joint acquisition program like this in the world. There have been examples of institutions jointly buying individual works but there’s never before been an initiative where two institutions together buy works over many years. We persuaded Qantas to gift AUD 2.5 million to a joint acquisition program, over five years, of Australian contemporary art, that would be jointly owned by the Tate and the MCA, and which would acquire living Australian artists to show in a global context in the Tate and MCA collections. We’ve now had every year since 2015 the Tate curators come down to Australia. They visit 30 or 40 artists and with that money, they bought, together with the MCA, a large body of works that are now being shown in an integrated way in the Tate collection. That’s been fantastic for the Australian artists, who’ve never really been able to have a profile in international museums. In fact, the Tate has historically thought of indigenous art not as art, notwithstanding indigenous art is the longest continuous culture – 60,000 years. They thought, like most institutions, that that type of work belonged in encyclopaedic museums like the Met rather than museums of modern art, but as a consequence of the curators visiting Australia over the past 5 years on a continuous basis, they now absolutely turned upside down the way they think about First Nations art. They have recently appointed the inaugural First Nations curator and they are now putting First Nations art from Australia and Canada and South America central to the way they think about art making today. Although the works they’ve been buying together with us have been both indigenous and non-indigenous, the impact of the curators getting to understand indigenous art has been transformational for the Tate. That’s something I’m particularly proud of having achieved for Australia.

Venice Biennale

In 2013 Simon was appointed Commissionaire of the Australian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Since 1988 the site had been occupied by what had been intended to be a temporary building, designed by prominent Australian architect Philip Cox and situated in the western edge of the Giardini.

“Australia was the last country to be granted a permanent site in the Giardini in Venice. In 1988, which was our bicentennial year, following extensive lobbying by Franco Belgiono-Nettis,(5) we were given a block of land, the only waterfront block, in the gardens. A temporary pavilion was built very quickly to enable Australia to have permanent representation.” The first artist to be shown in the pavilion was painter Arthur Boyd (1920-1999).

“I’ve been involved in Australia’s activities in Venice for 30 years and it was clear to me, that the temporary pavilion was no longer optimal for showing great Australian art. Venice is a very important window for any country, because it is the only biennale that has national pavilions. In the vernissage week you have 30,000 curators and art critics from around the world descending on Venice to look at what is considered each country’s best contemporary art of the time. If you have a suboptimal piece of infrastructure, you’re not able to present your artists in the best way. I made a proposal to the Australian government that we should look to redevelop the pavilion into something that was more reflective of contemporary Australia and was better placed to position Australian contemporary art in a global context.

“Together we commissioned a feasibility study and were surprised to find out that the temporary pavilion that was constructed in 1988 was the only non-heritage listed building in the gardens….As a consequence of that, we were able to get Venetian authority approval to redevelop that site. Fortunately the original architect, Philip Cox, was still alive and he was willing to consent to his temporary building being removed. Denton Corker Marshall won the architectural commission and I drove the campaign to raise the money to build the pavilion, which opened six years ago to enormous acclaim. The other countries that are represented in Venice were extremely jealous that Australia had built this extraordinary building. I think the combination of the Tate partnership, a world class building in Venice, and the extraordinary success of the MCA significantly enhances Australia’s position internationally in the arts.”

“There are a small number of very strong commercial galleries that exhibit at international art fairs and represent the key Australian living artists. Because we’re all able to travel – pre Covid – a lot more than people used to do 50 years ago, and because we’re able to go to international art fairs and biennales, we see non-Australian art in a different way and many collectors find seeing something new more exciting than seeing the same art that all your friends have at home. There are some great Australian living artists. There are a number in our collection that we’ve supported for 30 plus years like Shaun Gladwell, Janet Laurence and Lindy Lee.. There are a number from whom we own multiple works over their career but generally we’re finding non-Australian art to be more challenging at the moment.” I agree on this but disagree on the Australian commercial gallery scene, which I think is weak compared to other places around the world. In my view, this partly is a function of environment but there is a big difference between exhibitions being held in commercial galleries in Australia and other places. Berlin is smaller than Sydney and nowhere near as wealthy. This is an extreme example because Berlin is an art center for other reasons, not least, rental, milieu, opportunity and history, but we could also look at Beijing, which can be a very difficult environment to hold exhibitions now. I suggest to Simon that the Australian commercial gallery scene could be much stronger, certainly in terms of the international art market. They have almost zero input into Art Basel for instance or the galleries that select exhibitors for Art Basel or Fiac in Paris, which incidentally is run by Jennifer Flay, a New Zealander. This is something that has to get much stronger because you can’t have museums doing all the heavy lifting for an entire art market, it is impossible and not desirable either. A broad, transparent market with lots of talented professionals makes a big difference and that’s something that is still missing in Australia. “I’m not sure that you’re correct. We spend a huge amount of time travelling. Whilst we get challenged by things we see in other places, whenever we come home, we realize what a great group of independent galleries we’ve got. It’s not like New York where you’ve got Zwirner, Gagosian and Pace, which really are museum-like equivalent institutions. But we have a very strong group of independent galleries who are doing a great job, domestically supporting their artists and investing in things like the Hong Kong art fair and the New Zealand art fair, which are very expensive things for independent galleries to do, but they are constantly seeking to broaden their collector base…I think the Australian galleries are doing a pretty good job.”

What would you like to see develop in the Australian scene? What still requires support or a new direction? How would you like to see things develop in the next ten years? “I’d like to see a broader commercial network, but I also recognize the economics of running a gallery are extremely challenging. You need to sell a lot of art to be able to cover your overheads, particularly if you’re playing the international art fairs as well. And the price points of most Australian art make that extremely challenging. A living Australian artist that is selling work for six figures would be very unusual. A living Australian artist that is selling work for seven figures – I can’t think of one; and recognizing our currency is about half to the US Dollar, you can quickly see how the economics of a gallery are very hard, but I’d like to see a deeper arts ecology, including universities taking art schools more seriously. We’ve got a strong museum base but finding more commercial galleries, encouraging artists and supporting artists, that’s something I’d love to see over the next ten years.

“What surprises me is the number of homes we go into, usually designed by great architects, have cost a huge amount of money and the owners have nothing on the walls. The commercial gallery space can be quite intimidating when you first embark on that journey and having people who can hold your hand and give you comfort is a help. If you go into a car showroom you don’t get challenged if the BMW or Mercedes Benz is costing you 50,000 dollars, you pay the price. You might haggle a bit, but you pay the price. If you go into a commercial gallery, and the artwork costs 50,000 dollars, the first thing you want to know is whether you’re getting value or not. And I find that quite surprising. If you are buying a car for 50,000 dollars and not being concerned whether that’s value or not, why should it be any different if you see something beautiful like an artwork? Why should you be intimidated by that?”

“I’m surprised by the number of my contemporaries who have no art, who when I ask them why they don’t have any art; say they don’t understand the value. And when I point out that they have no concerns buying a car or a boat, where there is no value other than what’s on the pricetag, they really don’t have a response. They’re just anxious that they don’t know enough, and they are going to be buying something that’s going to be worth less in the future.”

***

“If we love an artwork and can afford it, and it has an emotional impact on us, we’ve never questioned the value. We obviously seek a collector’s discount, but given we’ve never sold a work of art, people [artists and galleries] aren’t worried about us flipping…We’ve often signed contracts to agree to gift works to institutions, which we’re very happy to sign, because we don’t have any intention to trade.”

5 May, 2020

Sydney and Saigon

Cav. Simon Mordant AO was chair of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney from 2010 to July 2020. Besides his close work with the MCA, Mordant is also Board Member of MoMA PS1, New York, a member of the International Council of MoMA, New York, a member of the Executive Committee of the Tate International Council, a director of MOCA in Los Angeles and a board member of the American Academy in Rome, as well as a former director of the Sydney Theatre Company, Opera Australia,and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. He was Australia’s Commissioner at the Venice Biennale in 2013 and 2015.Simon is an investment banker during the day.

Notes

1. Leon Paroissien (b.1937, Ghisborne, Victoria) was director of the MCA from its inception in 1989, through its opening in 1991, until 1997. He had been Curator of the Power Gallery of Contemporary Art at the University of Sydney from 1984-1989. Co-curator at the university and then Chief Curator at the MCA was Bernice Murphy, who succeeded Paoissien but resigned in November 1998, ostensibly to run an art magazine but it was thought, “the move was at least partly a response to the chronic state of financial crisis in which the museum had been operating for several years and which had created a level of stress on the staff that was simply too much to deal with. The MCA has never been properly resourced; as the prophetic article by Joanna Mendelssohn in Art Monthly (July 1998) explains, unlike the AGNSW and the Powerhouse Museum which receive a large portion of their funds from the NSW governenment, it receives almost no government money. The Power Bequest, upon which the Museum was founded, only provides 6% of the annual turnover of around $7.5m.” MCA Sinking Fast, Edblog, Artlink, December 1998 https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/2540/artrave/

2. Louise Schwartzkopf, ‘In Utzon’s shadow: the other architects shunned by the city’, July 3, 2009, Sydney Morning Herald https://www.smh.com.au/national/in-utzons-shadow-the-other-architects-shunned-by-the-city-20090702-d6k8.html

3. Paul Keating, ‘Michael Brand’s plan for the Art Gallery of NSW is about money, not art’, November 24, 2015, Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/opinion/paul-keating-michael-brands-plan-for-the-art-gallery-of-nsw-is-about-money-not-art-20151124-gl6j7x.html

4. Jori Finkel, ‘Topping a million visitors: how MCA Australia broadened the appeal of contemporary art’, The Art Newspaper, April 4, 2019.

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/analysis/broadening-the-appeal-of-contemporary-art

5. Franco Belgiorno-Nettis (20 June 1915 – 8 July 2006) was an Italian-Australian industrialist and philanthropist. After migrating to Australia in the 1950s he established Transfield. Belgiono-Nettis was an avid art collector and cultural philanthropist, in 1961 establishing the Transfield Art Prize, which became one of the most important art prizes in Australia. In 1973 he helped establish the Australian Biennale, later renamed the Biennale of Sydney).

![Simon with his parents [...]](http://www.randian-online.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Mordant-child-px-w720-copy-528x704.jpg)