Originally published in English in Particular Cases, by Boris Groys. Repinted with the permission of the author, along with the Chinese translation.

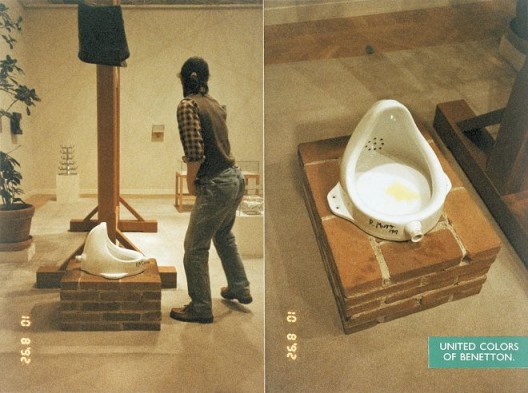

Inga Svala Thórsdóttir and Wu Shanzhuan’s manifesto and series of works titled Thing’s Right(s), a revision of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, cuts to the core of the Western cultural tradition—to the relationship between art and human rights, the French Revolution and aesthetic contemplation, the privileging of men and privileging of artworks. (1) I would like to use this intervention by Thórsdóttir and Wu into the Western art tradition as a starting point of my text. This intervention has the character of a protest, a contestation. Its primary target is the readymade practice as it was introduced by Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp’s art became a target for Thórsdóttir and Wu’s artistic actions early enough: in 1992, as the first collaboration with Thórsdóttir, Wu pissed into one of the urinals signed by Duchamp that was on display in the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. The title of the work was “An Appreciation”.

One could say it was also a violent reaction. But it was obviously a reaction against a certain kind of violence that was applied by Duchamp himself to the things that were taken out of their original everyday context and then, under the name of “readymades,” moved into the space of the art museum. One can say that Duchamp’s artistic decisions have (unjustly) privileged certain things in relationship to other things: for example, a particular urinal in relationship to all the other urinals. Indeed, even if some art theorists argued that the readymade practice erased the border between museographed art and ordinary reality, or between artworks and ordinary things, the selection of a particular urinal (or several particular urinals) has not emancipated its brethren that remained on their accustomed places inside lavatories all around the world. However, this is not the main objection that Thórsdóttir and Wu have with the readymade practice. For the artists, the true “appreciation” of a thing is precisely the use of this thing. According to this view, Duchamp insulted the urinal by forbidding its use. Thórsdóttir and Wu’s reaction to Duchamp’s gesture reminds us of the opposition between “ritual value” and “exhibition value” that was introduced by Walter Benjamin. Indeed, the usual use of the urinal can be understood as a kind of ritual that is negated and destroyed by the defunctionalization of the urinal in the exhibition space.

Inga Svala Thorsdottir & Wu Shanzhuan, “An Appreciation”, Cibachrome, 124.9 x 152.7 cm,1992(Courtesy of Long March Space)

吴山专 & 英格-斯瓦拉·托斯朵蒂尔,《一个欣赏》, CB相纸,124.9 x 152.7 cm,1992(图片由长征空间提供)

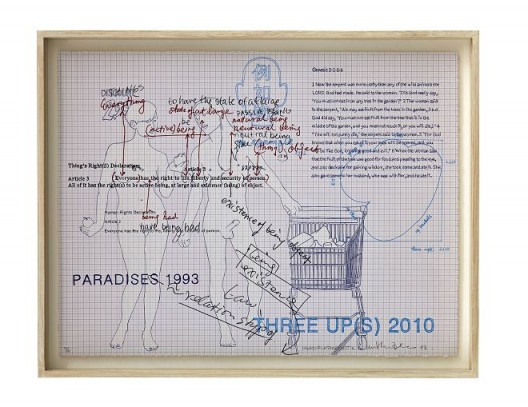

Inga Svala Thorsdottir & Wu Shanzhuan, “Paradises”, Cibachrome, 126.2 x 156.7 cm, 1993(Courtesy of Long March Space)

吴山专 & 英格-斯瓦拉·托斯朵蒂尔,《天堂们》,CB相纸,126.2 x 156.7 cm,1993(图片由长征空间提供)

The act of violence that removes an object from its immediate context of everyday use, isolates it, and prevents it from being plunged back into the flow of the quotidian has its historical roots in the violence of the French Revolution and its ideology of human rights. Indeed, our contemporary notion of art has its roots in the decisions that were taken by the French revolutionary government concerning the objects that it inherited from the ancien régime. The change of a regime—especially such a radical change as was introduced by the French Revolution—is usually accompanied by a wave of iconoclasm. One could watch these waves in the cases of Protestantism, La Conquista, or recently after the fall of the socialist regimes in Eastern Europe. The French revolutionaries took a different course: instead of destroying sacral and profane objects belonging to the ancien régime, they defunctionalized them—or, in other words, aestheticized them. The French revolution turned the things of the old regime into what we call today art—i.e., into an object not of use but of pure contemplation. This violent, revolutionary act of the aestheticization of the old regime created art as we know it today.

The revolutionary origin of modern aesthetics was conceptualized by Immanuel Kant in Critique of the Power of Judgment, written in 1790. Toward the beginning of his text Kant refers (albeit indirectly) to the political context of his time. He writes: “If someone asks me whether I find the palace that I see before me beautiful, I may well say that I do not like that sort of thing [ ... ] in true Rousseauesque style I might even vilify the vanity of the great who waste the sweat of the people on such superfluous thing. [... ] All of this might be conceded to me and approved; but that is not what is at the issue here. [ ... ] One must not be in the least biased in favor of the existence of the thing, but must be entirely indifferent in this respect in order to play the judge in matters of taste.” (2) Kant does not like the palace as a representation of wealth and power. However, he is ready to accept the palace as aestheticized, which actually means defunctionalized, made nonexistent for all practical purposes—reduced to pure form. Since the French Revolution, artworks began to be understood as defunctionalized and publicly exhibited things of a past reality. This understanding of art determines artistic strategies up until today. One can say that Duchamp and other artists of the readymade expanded this strategy to include its own contemporaneity: this contemporaneity was seen by them as already past, a disappearing reality that can be easily reduced to pure form. And as pure form it became unusable. The fact that the artworks are not used means that they have their goal not outside, but inside themselves. In this sense, artworks are “humanized” things: they have a “soul” that makes them autonomous. The modern humanist ethics is based on the requirement that man can never be a means, only a goal. In this sense, artworks are treated like men among things. But one can also say that men are treated like artworks among animals. Here one can see a deep and decisive connection between the autonomy of things and their form. Things become protected artworks when they are perceived only as “forms” and not as usable objects—and animals become protected from use when they have a human form. Thus, speaking about the rights of things, Thórsdóttir and Wu point to the core of the problem—the connection between art and humanism. But what, actually, is a thing?

According to Martin Heidegger, only an artwork can manifest itself as a thing. In his essay “The Origin of the Work of Art” (1935–36), Heidegger writes that we originally encounter all things as “tools.” In other words, we always perceive them as objects of possible use—and thus overlook precisely their thingness. Art alone is able to demonstrate to us the thingness of things by taking them out of the context of their ordinary use. Thus Heidegger writes: “Nothing can be discovered about the thingly aspect of the work until the pure standing-in-itself of the work has clearly shown itself. But is the work in itself ever accessible? In order for this to happen it would be necessary to remove the work from all relation to anything other than itself in order to let it stand on its own and for itself alone.” (3) But if our ability to experience the work of art “on its own and for itself alone” depends on the decision to remove it “from all relation to anything other than itself,” such a decision must in some way be unfounded and unprecedented. Heidegger writes: “The setting-into-work of truth thrusts up the extra-ordinary (das Ungeheure) while thrusting down the ordinary, and what one takes to be such. The truth that opens itself in the work can never be verified or derived from what went before. In its exclusive reality, what went before is refuted by the work. What art founds, therefore, can never be compensated and made good in terms of what is present and available for use. The founding is an overflowing, a bestowal.” (4) And at another point: “The more essentially this thrust comes into the open, the stranger and more solitary the work becomes.” (5)

Inga Svala Thorsdottir & Wu Shanzhuan, “Posing for Swimming”, Cibachrome, 125.3 x 124.6 cm, 1994(Courtesy of Long March Space)

吴山专 & 英格-斯瓦拉·托斯朵蒂尔,《为游泳的姿势》,CB相纸,125.3 x 124.6 cm,1994(图片由长征空间提供)

Inga Svala Thorsdottir & Wu Shanzhuan, “Pouring Bottled Water into the Victoria Harbour”, Cibachrome, 181.7 x 124.5 cm, 1993(Courtesy of Long March Space)

吴山专 & 英格-斯瓦拉·托斯朵蒂尔,《往维多利亚港中倒矿泉水》,CB相纸,181.7 x 124.5 cm,1993(图片由长征空间提供)

What presents itself in these passages as a mere description is evidently a normative proposition: the work of art cannot be understood in terms of the past; it breaks with the habits of perception. Though Heidegger himself did not have particularly “progressive” artistic taste, and evidently stuck with moderate expressionism, his theory of art nonetheless privileged a radical, avant-garde, innovative art by encouraging the artist to present the decidedly “extra-ordinary.” The extra-ordinary here is obviously not merely a historical innovation, but the extraction of the artwork from the ordinary. Here Heidegger seems to speak a language that is very similar to the language of Duchamp: we can see the urinal as a thing only if we remove it from everyday use. Or, the urinal becomes a thing only after it has become an artwork. Before that it was merely a tool. In other words, to expand human rights, as understood by the French Revolution, to the realm of things means to defunctionalize them—so that these things can be only contemplated but not used. Under such a presupposition to speak about the right of things means to turn the whole of ordinary life into an artwork or a museum space, or to completely destroy it. That is the actual problem that Thórsdóttir and Wu address with Thing’s Right(s). But before we come back to this problem let us discuss the following question: Is the art system the place that guarantees things their thingness—by completely relieving them from their role of tools?

Heidegger was famously more than skeptical about the role of the art system. He writes: “Well, then, the works themselves are located and hang in collections and exhibitions. But are they themselves, in this context, are they the works they are, or are they, rather, objects of the art business? […] Official agencies assume responsibility for the care and maintenance of the works. Art connoisseurs and critics busy themselves with them. The art dealer looks after the market. The art-historical researcher turns the works into the objects of a science. But in all this many-sided activity do we ever encounter the work itself?” (6) The answer, of course, is no. Paradoxically, the art system turns the artworks back into tools—their thingness is overlooked again. For Heidegger, the artwork is an event that takes place in the “clearance of Being.” However, entering this clearance, this opening of Being, the artist immediately sees its closure. Of course, the art system is not a supermarket. When I buy a thing in a supermarket I can use it as I please—I can even destroy it. But I cannot freely use or destroy a work of art —I cannot “enslave” it, turn it into a tool instead of keeping its status as a goal. Such a behavior would be judged as barbaric by contemporary society.

Nevertheless, I can use an artwork as a sign of power and wealth. Even if the art system negates the ordinary use value of a thing, it keeps its exchange value intact. From the Marxist point of view (as formulated in the first volume of Marx’s Capital), art can be seen as the ultimate stage of “commodity fetishism,” and the readymade practice as the final triumph of exchange value over use value: the moment at which a readymade ceases to remain as a pure object of contemplation and begins to circulate inside the globalized art world, the soul of the thing is substituted by its price. Thus, the actual accusation directed against the art system is this: the art system uses art as art—whereas art should not be used in any way, including as art. It is precisely this use of art as art that has produced so much criticism and negative reaction recently against the art system all over the world. The Heideggerian return to the truth of art as an opening of the world seems increasingly improbable in our days. So the answer to the use of art as art is mostly: the use of art as nonart. Art becomes politicized and subjected to “good” social goals.

However, in Thing’s Right(s), Thórsdóttir and Wu offer a different way of dealing with the same problem: the aestheticization of the use of things as such. Or, in other words, the aestheticization of ordinary life in its totality. In the context of the reflection on the relationship between the aestheticization of politics and the politicization of aesthetics, undertaken in the epilogue to “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), Walter Benjamin critiques the aestheticization of politics as the Fascist project par excellence. Namely, Benjamin interprets the aestheticization of life, including politics, as a proclamation of the war of art against life, and summarizes the Fascist political program by the words: Fiat ars—pereat mundus. Benjamin writes further that Fascism is the fulfillment of the l’art pour l’art movement. (7)

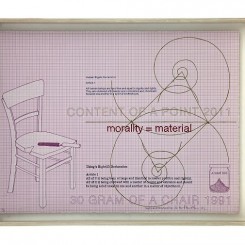

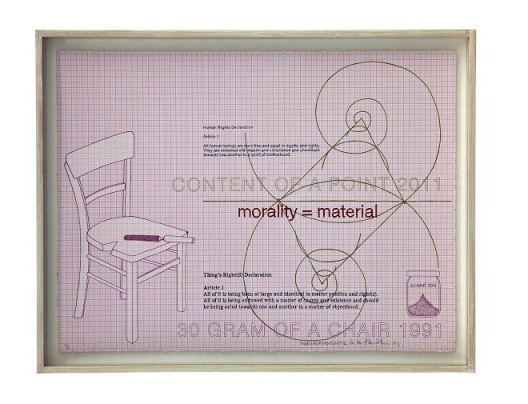

Inga Svala Thorsdottir & Wu Shanzhuan, “Thing’s Right(s) Printed 2013, Article 1”, lithography, screen print on Stonehenge paper, 55.5 x 73 cm, 2013(Courtesy of Long March Space)

吴山专 & 英格-斯瓦拉·托斯朵蒂尔,《物权版画2013 第一条》,纸上丝网、平板印刷,55.5 x 73 cm,2013(图片由长征空间提供)

Inga Svala Thorsdottir & Wu Shanzhuan, “Thing’s Right(s) Printed 2013, Article 2”, lithography, screen print on Stonehenge paper, 55.5 x 73 cm, 2013 Ed. 3/6(Courtesy of Long March Space)

吴山专 & 英格-斯瓦拉·托斯朵蒂尔,《物权版画2013 第二条》,纸上丝网、平板印刷,55.5 x 73 cm,2013 Ed. 3/6(图片由长征空间提供)

Benjamin comes to this conclusion because he still understands art as pure contemplation beyond any use. In that case the aestheticization of the totality of everyday life would indeed amount to stopping and destroying it. However, the aestheticization of the use value of things changes this equation in the most radical way. Wu has the experience of Chinese communism behind him—in other words, he has experienced a total aestheticization of reality to a degree that Western artists never have. And one should not forget: economically speaking, communism is nothing other than victory of use value over exchange value. Under the conditions of communism, the market, including the art market, gets abolished. And that means that communism starts with the exchange value of things reduced to a zero level. The use value that earlier depended on the exchange value becomes artistically reinvented or even newly invented. Here, the ordinary itself becomes extra-ordinary—and thus, according to Heidegger, a work of art.

This constructivist character of communist society—when all things become reduced to zero and then reinvented together with their use—finds its correspondence in Suprematist, or Constructivist, art practices, as well as reductionist practices of postwar and more recent art. Not accidentally, Thórsdóttir practices the pulverization of things in her own art. Her pulverization practice reminded me of a project to burn all existing artworks, proposed by Kazimir Malevich in 1919. At that time the new Soviet government feared that the old Russian museums and art collections would be destroyed by civil war and the general collapse of state institutions and the economy. The Communist Party responded by trying to secure and save these collections. In his text “On the Museum,” Malevich protested against this pro-museum policy of Soviet power by calling on the state to not intervene on behalf of the old art collections because their destruction could open the path to true, living art. (8) Malevich proposes not to keep or save things of the past that have to go, but to let them go without sentimentality and remorse. To let the dead bury their dead. And at the same time Malevich professes his love for the new objects of ordinary use as belonging to the creation of the new world. In other words, it is the reduction to dust (or pulverization) of the old things along with the destruction of their exchange value that opens the way for new things to have a new use value.

Here one can see the difference between the French Revolution and the Communist Revolution. The French Revolution will establish human rights but it is, indeed, not interested in the rights of things. In other words, it wants to regulate the relationship among men—but not the relationships among things. That is why the French Revolution remained stuck halfway: it liberated ordinary life, but did not artistically transform or reinvent it.

When Heidegger speaks about the ability of art to show the truth of things, he means that their truth lies in their ordinary use. As an example, Heidegger cites a pair of worn-out shoes presented by Van Gogh in one of his paintings. Heidegger assumes that these shoes are so radically used that they have no exchange value any more—only use value. But the painting itself obviously has an exchange value. And a new pair of shoes, not yet worn-out, would have an exchange value too—at least in the society in which Heidegger lived. The interesting aspect of communist society is that a new pair of shoes only has a use value—and no exchange value. Thus, this pair of shoes does not need to wait to become worn-out, unwanted, or unsellable on the market in order to become aestheticized by Van Gogh and/or Heidegger. In a communist society the rule of the use value is total (what isn’t usable is forbidden; who doesn’t work doesn’t eat) and includes things and humans alike. It is this experience of the total artwork based on use value that Thórsdóttir and Wu conceptualize in Thing’s Right(s).

However, the total does not mean totalitarian here. The use of things is total—but it remains undetermined. Wu writes: “I believe art is a silent ocean. […]It is a static, formless empty box—it must accept absolutely anything, absolutely anyone, and it is destined never to be full. Its strength is in nothingness.”(9) Related to this notion of art, Wu’s concept of the “deficit (red) character”— that words or characters do not have one single meaning—-and his idea that “methodology of presentation precedes the existence of a concept, remind me of the elegant theory that was formulated by Claude Lévi-Strauss as he tried to conceptualize the notion of mana that was used by Marcel Mauss in The Gift (1925).

The term “mana” that Mauss uses derives from the relatively closed orbit of Polynesian culture. Mana can be understood as an exchange value of a thing that is given as a gift. However, it is of crucial importance to Mauss’s theory of mana that the character of this exchange value changes over time. At first, the mana within the gift is always benign, but later it necessarily begins to exert a negative effect on its new owner—because its connection to the gift-giver begins to be forgotten. Good mana is guaranteed as long as the strangeness of the gift has not been forgotten. The inevitable domestication of the gift later on not only leads to the loss of positive mana, but also to the rise of negative mana. We might say that as soon as the sign of the new and strange becomes part of the familiar surroundings, it becomes a locus of negative powers and feelings. We encounter this phenomenon as the cycle of fashion: those who dress themselves according to the latest fashion appear hip and attractive, yet nothing is more detrimental to one’s image than last year’s fashion. Decades-old fashion, by contrast, might signify “return,” and thus acquire positive mana and become attractive again. Fashion, in fact, is nothing other than a particular form of the economy of symbolic exchange, which forces all people to exchange their signs constantly in order for these signs to appear forever strange.

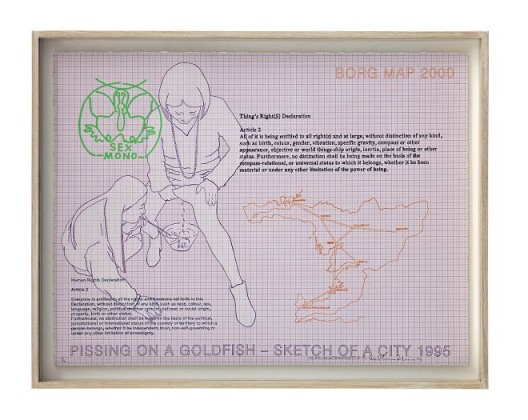

Inga Svala Thorsdottir & Wu Shanzhuan, “Thing’s Right(s) Printed 2013, Article 3”, lithography, screen print on Stonehenge paper, 55.5 x 73 cm, 1993(Courtesy of Long March Space)

吴山专 & 英格-斯瓦拉·托斯朵蒂尔,《物权版画2013 第三条》,纸上丝网、平板印刷,55.5 x 73 cm,1993(Courtesy of Long March Space)

Wu Shanzhuan & Inga Svala Thorsdottir, “Thing’s Right(s) Printed 2013, Article 4”, lithography, screen print on Stonehenge paper, 55.5 x 73 cm, 2013(Courtesy of Long March Space)

吴山专 & 英格 – 斯瓦拉·托斯朵蒂尔,《物权版画2013 第四条》,纸上丝网、平板印刷,55.5 x 73 cm,2013(图片由长征空间提供)

Mauss’s use of the term mana was criticized by many Commentators because its use seemed too dependent on Polynesian mythology. The most radical, most profound, and, at the same time, most theoretically important critique was formulated by Lévi-Strauss. Contrary to most critics, however, Lévi-Strauss did not want to abandon the term, but sought to endow it with a more precise definition. According to Lévi-Strauss, mana does not belong to the order of reality but solely to the order of signs. He assumes that at a certain point in time the entire universe suddenly experienced a revolution of signification, and became saturated with signs. Prior to this big bang of signification, there was no meaning at all in the world; afterward, there was only meaning. All things instantly became signs or, rather, signifiers, which ever since have each been waiting for their signified. So the world after the big bang of signification offers us an infinite number of signifiers, yet we do not know what they mean—they are signifiers without signifieds. We only know that they signify. The progress of thinking, says Lévi-Strauss, consists in “the work of equalising of the signifier to fit the signified”; that is, in the gradual filling of empty signifiers with particular meanings, with signifieds.

Yet the progress of thinking is very slow as well as always finite and partial. Although it takes place “inside a totality which is closed and complementary to itself,” or, to use Wu’s words, inside a box, it can never completely fill the infinite number of empty signifiers with signifieds, because every labor of thought is carried out in a finite lifetime. The basic condition of man in the world—understood as a world of signification—thus consists in the fact that the human always has far too many signs at his disposal to which he cannot assign meaning: “There is always a non-equivalence or ‘inadequation’ between the two [the signifier and the signified], a non-fit and overspill which divine understanding alone can soak up; this generates a signifier-surfeit relative to the signifieds to which it can be fitted.” Hence there always remains a “supplementary ration” of signifiers without signifieds that marks the difference between the infinite divine and our finite human reason—a difference humans must somehowcope with. According to Lévi-Strauss, mana is nothing else but the name for this surplus of empty signifiers that have no concrete meaning. Mana is the “floating signifier” that represents the entire infinite surplus of signifiers, and that is “the disability of all finite thought (but also the surety of all art, all poetry, every mythic and aesthetic invention), even though scientific knowledge is capable, if not of staunching it, at least of controlling it partially.” Hence, mana is “a zero symbolic value, that is, a sign marking the necessity of a supplementary symbolic content. (11)

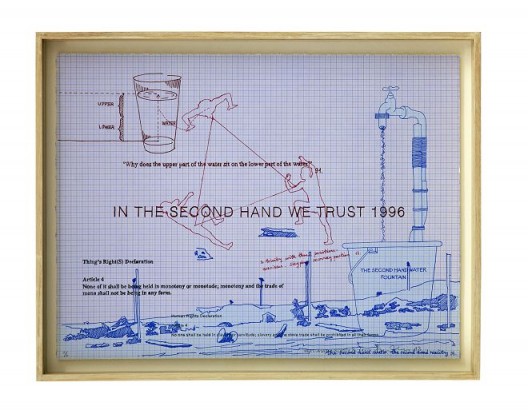

But what are these signifiers without a signified? Using the language proposed by Thórsdóttir and Wu, one can say that they are deficit things waiting for use—and this status of waiting is precisely the mana that makes them attractive and potentially poetic. The communist revolution can be interpreted as a version of the revolution of signification that Lévi-Strauss speaks of. It creates an ocean of floating things/signs that are waiting for use. Human beings are laborers who ascribe meaning to them. This is a poetic, artistic job. But it is not the only artistic job possible. Another job is precisely to thematize the floating character of things and signs—and the impossibility of its complete domestication and familiarization. Things and signs have the right to remain forever floating, foreign, strange—and fascinating. It seems to me that this right to be strange and extra-ordinary is what Thing’s Right(s) is aiming at. Let us be reminded of some of these rights. Every individual thing, in particular, “has the right(s) to be active being, at large and existence (being) of object” (Article 3), and “None of it shall be being held in monotony or monotude; monotony and trade of mono shall not be being in any form” (Article 4). Here, monotony is equated with slavery. Things should be Used—but in dynamic, unexpected, extra-ordinary ways. Only then would the aestheticization of life mean not its destruction, but its artistic reinvention. The only true human right and the only true right of things is the right to become extra-ordinary.

“CAUSE AND EXAMPLES PROJECTED FROM IT”,installation view, 2017, Long March Space, Beijing(Courtesy of Long March Space;Photography by Thomas Fuesser)

“起因和从中投射出来的例如物”,展览现场,2017,长征空间,北京(图片由长征空间提供,拍摄:Thomas Fuesser)

“CAUSE AND EXAMPLES PROJECTED FROM IT”,installation view, 2017, Long March Space, Beijing(Courtesy of Long March Space;Photography by Thomas Fuesser)

“起因和从中投射出来的例如物”,展览现场,2017,长征空间,北京(图片由长征空间提供,拍摄:Thomas Fuesser)

“CAUSE AND EXAMPLES PROJECTED FROM IT”,installation view, 2017, Long March Space, Beijing(Courtesy of Long March Space;Photography by Thomas Fuesser)

“起因和从中投射出来的例如物”,展览现场,2017,长征空间,北京(图片由长征空间提供,拍摄:Thomas Fuesser)

“CAUSE AND EXAMPLES PROJECTED FROM IT”,installation view, 2017, Long March Space, Beijing(Courtesy of Long March Space;Photography by Thomas Fuesser)

“起因和从中投射出来的例如物”,展览现场,2017,长征空间,北京(图片由长征空间提供,拍摄:Thomas Fuesser)

“CAUSE AND EXAMPLES PROJECTED FROM IT”,installation view, 2017, Long March Space, Beijing(Courtesy of Long March Space;Photography by Thomas Fuesser)

“起因和从中投射出来的例如物”,展览现场,2017,长征空间,北京(图片由长征空间提供,拍摄:Thomas Fuesser)

Notes

1. Thorsdottir and Wu started writing the Thing’s Right(s) Declaration in the early 1990s; the first English version was published on the occasion of their show “Thing’s Right(s)—Cuxhaven 1999,” Cuxhavener Kunstverein, 1999. It has since been published in Chinese, Sanskrit, Hindi, Swedish, Malay, and Tamil, on the occasion of different exhibitions.

2. Immanuel Kant, Critique of the Power of Judgment, ed. Paul Guyer, trans. Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 90–91.

3. Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” in Off the Beaten Track, ed. and trans. Julian Young and Kenneth Haynes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 19.

4. Ibid., 47.

5. Ibid., 40.

6. Ibid., 19.

7. Walter Benjamin, epilogue to “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 2007), 241–42.

8. Kazimir Malevich, “On the Museum,” in Essays on Art, 1915–1933, vol. 1, ed. Troels Andersen, trans. Xenia Glowacki-Prus and Arnold McMillin (London: Rapp &Whiting, 1971), 68–72.

9. Cited in Qiu Zhijie, “Introduction: Wu’s Question or the Questioning of Wu,” in Wu Shanzhuan: Red Humor International, ed. Susan Acret and Jasper Lau Kin Wah (Hong Kong: Asia Art Archive, 2005), 25.

10. Ibid., 24ff., 27.

11. Claude Lévi-Strauss, Introduction to the Work of Marcel Mauss, trans. Felicity Baker (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987), 61–63 (italics in original).