Art fairs in and around China are becoming increasingly “focused”. First came Photo Shanghai, presented by the World Photography Organization and Montgomery, and then came Ink Asia, founded by the director of Fine Art Asia, Calvin Hui. On December 16, 2015, Ink Asia opened at the Hong Kong Exhibition Center, featuring 42 art galleries, four special programs (“Ink+”, “Pioneers of New Ink”, “Hatching Project”, “Charity Exhibition, Farewell: Chu Hing Wah”) and four public art installations. Other than MD Flacks (London), all of the art galleries come from Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

As it is the host city, local art galleries from Hong Kong made up half of the exhibitors, with stalwarts present such as Hanart TZ Gallery, Alison Fine Arts, and Karin Weber Art Gallery alongside newcomers founded in the last five years such as Art Experience Gallery and Lucie Chang Fine Art. From Mainland China, 55 Art Space (founded by the collector Liu Shan), Taihe Art Gallery (uniquely devoted to ink art), and Huafu Art Space took part, among others. Moreover, local art academies and art associations also participated.

The fair director Calvin Hui believes that choosing Hong Kong, an international city, as the location for the fair may rectify the “traditional” understanding of ink art for the public (including the public overseas) and help them to reconsider the future of ink painting with an open mind. In Hong Kong, at least, ink art has managed to slip free from the dominant institutional style of the China Artists Association or that of the National Art Academy (under the Propaganda Department of the CPC Central Committee). In other words, they are not constrained by an overarching official ideology or by set themes representing the “majestic landscape” of the motherland or specific humanist/literary concerns; instead, a great diversity of works were present.

Though this was the inaugural edition of the fair, thanks to Calvin Hui’s background as the co-founder of the 3812 Art Gallery and the co-director of Fine Art Asia, Ink Asia reached a high level of professionalism in both structure and content. In comparison with some comprehensive art fairs—Art Beijing, Art021, and so on—the booth design was a highlight. MD Flacks, for instance, painted its booth in red and black to offset the quietude of monochromatic ink; placing Chinese-style furniture and jade bamboo screen added an extra touch to the booth. Song Yin Art, adept at rendering an “Eastern” ambience, created a garden within a garden by installing a round arch entrance. Others took the minimal approach: Galerie du Monde (Hong Kong) was set at a 45-degree angle, which offered a different visual effect through the strategic installation of Liu Guosong’s color and monochrome paintings.

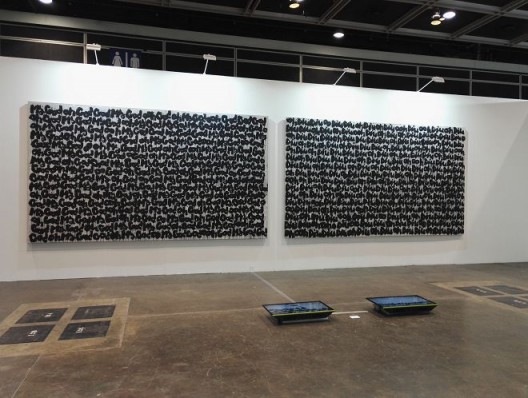

Yang Jiechang, Oh my God, Oh Diu, (Diptych) with vvideos, 2002

杨诘苍,《Oh My God》,《Oh Diu》, (双联)书写录影装置,2002

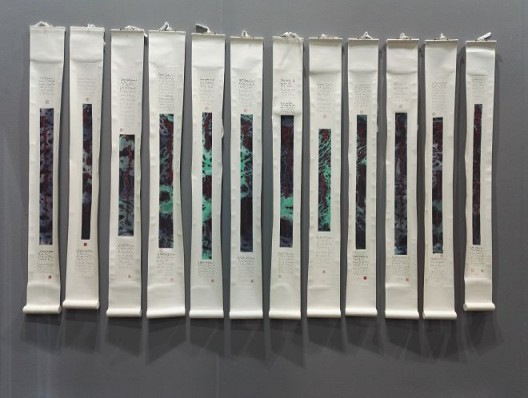

Larger public installations effectively interrupt any visual monotony for viewers. Examples included Shen Aiqi’s monumental “Ink Milestone” at Hanart TZ Gallery, Yang Jiecang’s video installation “OH MY GOD” presented by Alison Fine Art, and Xing Gang’s “N Dimension: Infinite Space” at 3812 Art Gallery.

Of course, it was impossible for all 43 art galleries to attain an even standard. Certain booths did not pay particular attention to framing or how the artworks were installed. What might have seemed messy at times fortunately did not affect the overall presentation of the fair.

The artworks painted a general overview of ink art from the last century to the present, including works by Liu Guosong who pioneered Taiwanese ink art in the 20th century; Li Jin, a figure in new literati painting, and Zhang Yu, a participant of experimental ink art, among others. Besides art practices from Mainland China, foreign works with elements of “ink” were also a major factor in the fair—in other words, works that adopt the materials of ink art, or its stylistic representations as well as its iconographies. Rasti Chinese Art brought a color on paper work by the promoter of contemporary Chinese ink painting, the collector Hugh Moss; there was also monochrome photography by Daniel Eskenazi’s and prints on silk by Fabienne Verdier at Alison Fine Art.

Aside from those works obviously identifiable as “ink” works (including those using the materials, icons, and traditional framing associated with “ink art”), video, new media, installation, ceramics, sculpture and other alternative” ink” works are embraced this edition. Calvin Hui does not believe that Ink Asia simply serves as a venue to show art, but rather functions as a site for experimentation and to explore the potential for aficionados sharing the same interests. Yet the outcome of such experimentation is not necessarily pleasant. The “Ink+” collaborative project by 17 artists from Mainland China and Hong Kong on one hand presented cross-disciplinary “ink” works, and yet on the other it could not avoid presenting some kitsch works of craft, such as a blue-and-white tissue box, simplistic mini-pines and installations with crude ink drawings. No matter what, either through appropriating the traditional materials of ink painting or drawing from non-traditional materials, or yet through integrating other artistic disciplines into “ink art”, it must be noted that the characteristics of ink art have never been this elusive and indistinct.

As early as in the 1950s, Taiwanese artists reformed traditional ink art through abstraction, thereby setting foot in modern art. During a wave of anti-classicism in the 1980s, by exploring new possibilities in ink art, Gu Wenda’s wanton appropriation of traditional ink materials and his rejection of traditional ink practice initiated his approach to of “experimental ink art”. Thereafter, such practices of employing the traditional tools of ink painting to serve as vehicles for modern artistic ideas have to a degree liberated artists focusing traditional ink practice. From singularity to diversity, from the two-dimensional to the three-dimensional, breakthroughs in material expanded the forms of representation in ink art. Yet, if ink merely serves as a tool for artistic experimentation, how can the artist articulate the attributes of “ink” when expressing their ideas? After all, art practices that involve a few strokes of ink, a few pieces of rice paper, or a few touches of the brush may fool the eye as “faux” ink works, while those artists who stand guard with the ink tradition would have absorbed its essence. One notices through conversations with most art gallery owners and ink artists that ”spirit resonance” (qiyun), brushwork, intellectual cultivation and an “Eastern spirit” are recurring terms—as though without them, the discourse would depart from the realm of “ink art”.

The “ink art” that emerged in the development of Chinese painting is an artistic feature that came about as the literati tended towards avoiding virtuosic technique in painting. The aesthetic attitude and cultural spirit it represents emanate from the person holding the brush. Yet as writing itself has undergone and is undergoing drastic changes, how should one cultivate this “ink art”? If the emphasis is placed on the literati’s cultivation of learning, the collapse of the old feudal society and the ensuing reforms had long led to the disappearance of the material foundations for such literati cultivation. Modernity thereafter had also struck at traditional culture critically, while contemporary artists—the professional painters—have rarely managed to match the traditional literati’s attainments. The new literati painting that emerged in the 1980s was none other than those ink painters’ momentary glances back at tradition amid the tumult of ideological emancipation, in which an individualized language overlooked the achievements of those who came before it.

Moreover, to consider Zen Buddhism and other strains of classical philosophy as the embodiment of the “Eastern spirit” that guides the practice of ink art does not itself have ancient roots; rather, it is a present-day “”invention”, since the history of writing and painting with ink existed much earlier than these ideas. Without doubt, intellectual refinement or accomplishments would ultimately have an impact on the artist’s practice. Yet when artists translate philosophical ideas into visual icons and then claim them as ink art without due reflection, the so-called “Eastern spirit”—embodying Confucian, Taoist, Buddhist ideas and what not—would inevitably become a mere means to an end. The signifier of ink art is constantly drifting. Rather than single-mindedly focusing on experimentation and creativity, the issue of how to dispel the mystique in ink art is perhaps the issue worth exploring at Ink Asia in the future.

Yet perhaps the focus on a singular artistic medium resulted in an opening day that was not overwhelming; the number of visitors over the four days of the fair reached a total of ten thousand. As for sales, the local art galleries had an advantage. Liu Guosong’s painting “Snow-Covered Mountain Range” presented by Galerie du Monde was sold for 10 million HKD to a British collector during the VIP preview, and the other three or four works by the same artist were sold to Southeast Asian collectors. Calvin Hui’s 3812 Art Gallery also made sales of five works on the evening of VIP preview. Mainland China galleries such as BA Art Space, EGG Gallery, Huafu Art Space, and Triumph Art Space, meanwhile, had many inquiries without making any sales. Nevertheless, visitors were on the whole hopeful for Ink Asia, and believed that an art fair focusing on ink art could help the viewers come to grips with the practice of ink art, cultivating collectors for both Chinese and foreign artists. Like most art fairs, Ink Asia aims to open up the European and American markets, drawing the attention of art galleries and collectors to contemporary ink art in Europe and America.

Shen Aiqi, “Cliffs Growing”, ink and colour on paper, 179X179cm, 2013

沈爱其,《石岩在生发》,水墨设色纸本,179X179cm, 2013