Since March this year, a Chinese mummy-statue from the Drents Museum (in Assen, The Netherlands)—part of a mummy exhibition held at the Hungarian Natural History Museum since October 2014—has caused a media uproar internationally. Based on initial assessments by experts on Chinese cultural relics, the Zhanggong Zushi statue’s origin was determined to be Yangchun—a village in Datian County in China’s Fujian Province. It was allegedly stolen in 1995 and transported abroad, ultimately falling into the hands of a Dutch collector.

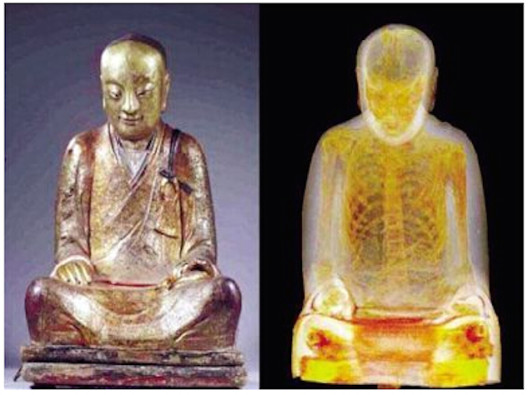

The mummy statue was made by embalming the remains of a highly revered monk after he died. Chinese media has cited conclusions made by a Dutch research team led by Erik Bruijn, an expert on Buddhism, stating that this controversial thousand-year-old Buddhist statue may very well contain the remains of the Liao Emperor Yelü Dashi’s tutor, a Zen monk with the title of Zhanggong Zushi who lived during the Northern Song Dynasty (A.D. 960–1127). However, this gilded statue could just as easily be a folk idol worshiped by generations of Yangchun villagers in southern Fujian. Regarding the statue’s identity, the Hungarian Natural History Museum had labeled the statue as “liuquan” (“six complete”). This does not refer to the monk’s name but rather is a reference to its intact head, limbs and body.

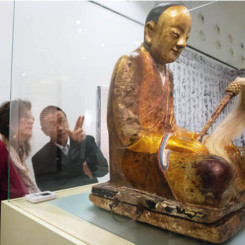

In order to clarify the statue’s true origins, members of the media arrived in Yangchun Village in Fujian to interview Lin Yongtuan, a villager who worshipped the statue for two decades, “As soon as I saw it, I knew it was the one we lost. I took a quick screenshot and called one of the villagers who’d taken a photograph of Zhanggong Zushi many years ago. The two of us showed the photo and the screenshot to the village elders. When the Zhanggong Zushi was still in our village, he wore a headpiece, so when we took the screenshot and covered up the top of the statue’s head, we immediately recognized it as the statue we lost.” Not long after the statue disappeared from Fujian, a Dutch collector acquired the statue through “legal means” in 1996, and later loaned it to a local museum for research and exhibition.

Last month, however, the Dutch collector spoke up to say that the statue had appeared in Hong Kong in late 1994, and therefore could not be the Zhanggong Zushi statue from Fujian. The individual subsequently expressed his willingness to return the high-priced statue if provided with sufficient evidence from China.

From a legal standpoint, this Buddhist monk statue has already been deemed a “stolen cultural relic” by China’s State Administration of Cultural Heritage, and negotiations with the Netherlands have been set in motion. However, in addition to the identification of the statue as a cultural relic, the greatest difficulty at the moment lies with the law. There is no bilateral agreement currently in place between China and the Netherlands regarding the recovery of artifacts. Neither the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property 1970 nor the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects fully apply in this case because the Netherlands has yet to recognize the legality of these regulations. Past cases of the successful repatriation of Chinese artifacts have generally relied on the role played by overseas Chinese and domestic private capital in auctions, where individuals or groups place winning bids on lost relics and subsequently return them to their origins.

This controversial statue is not the only Chinese “mummy” in existence. With the increase in production of mummy statues following the rise and spread of Buddhism in the region after the Tang Dynasty, Fujian is a major hotspot for relics of this nature. One of the most famous examples of these is the mummy of the Sixth Patriarch in Nanhua Monastary located in Guangdong Province. Mummy statues are also found in other regions around China, including the Buddhist mummies at Jiuhua Mountain.