“Zeng Fanzhi: Paintings, Drawings, and Two Sculptures”

Gagosian Gallery (555 West 24th Street, New York, NY 10011) November 6 to December 23, 2015

In 2013, Zeng Fanzhi’s (b. 1964) “Last Supper” (2001) was sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong at the Asian Contemporary 40th Anniversary Sale for a record-setting $23.3 million USD. In an instant, Zeng, who had been rising to prominence since his Hospital series in the 1990s, became both a household name to the art world and, coincidentally, a good investment. Shown recently at Gagosian Gallery in New York, “Zeng Fanzhi: Paintings, Drawings, and Two Sculptures” features Zeng’s new works: gone are the gory images of “Meat” (1992) and the masked self-conscious urbanites of his Masks series of the mid-1990s and 2000s. In their place are new, massive panels depicting shadowy landscapes, solitary figures, and a mixture of Buddhist and classical Western imagery. What remains, however, are the strategies of display that draw big crowds yet continue to marginalize Chinese contemporary artists.

Since the 1990s, Zeng Fanzhi’s art has been an exploration of different styles, borrowing techniques from Western masters and movements such as Francis Bacon and German Expressionism, all in the quest to find his own voice. Rather than remain confined to pre-established cultural boundaries, Zeng’s work plays with them, generating archetypal figures from the everyday, and casting them within the tension of an ever-globalizing China. With his Hospital and Meat series, Zeng utilizes the striking visual manner of German Expressionism, portraying common people caught in the grip of psychological pathos and modern exploitation. Daily scenes such as hospitals and butcher’s shops become settings for his contemporary religious icons. A Christian Pietà is set against piles of the sick, mirrored by the fleshy visions of hanging meat. These subjects become sacrificial lambs amid the progress of China’s new economy. Zeng’s Mask series continued this, producing portraits of Communist youth and corporate businessmen in suits and ties, all showing strained exuberance upon a ghostly visage. The mask both obscures and reveals a bitter tension, anxiety and alienation within a collectivist society coming to grips with globalization and their own commodification. It was with the record-setting sale of “Mask Series 1996 No. 6” (1996) in 2008 and, later, his “Last Supper” in 2011 that Zeng became instantly known to both Chinese and Western art collectors. Coincidentally, it was in 2011 that Gagosian obtained the rights to represent Zeng’s work internationally.

Zeng Fanzhi, “Paintings, Drawings and Two Sculptures”, exhibition view. Artwork © Zeng Fanzhi Studio. Photography by Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

曾梵志,”油画、素描和两件雕塑”,展览现场

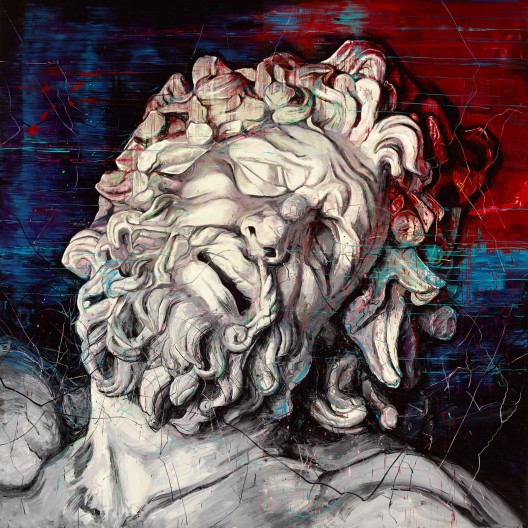

Recently displayed at Gagosian, Zeng’s “Paintings, Drawings, and Two Sculptures” showcased Zeng’s newest approach to his art. Dark landscapes and cursory figures rendered with broad strokes of paint, heavy impasto, and a freeness of line and structure mark a departure from the previous decades. This break is, however, a conscious and intellectual one, with Zeng’s work referring more to Song-dynasty painting than a superficial resemblance to paintings by Jackson Pollock, Jean-Paul Riopelle, or Anselm Kiefer. Zeng’s paintings, the production of which he described in a 2007 interview filmed by Hong Kong-based filmmaker Ringo Tang as a “meditation”, reflect on the Buddhist perception of the ephemeral nature of life and the Taoist notion of constant change apparent in nature. Within this context, even his figurative paintings take on new meaning. His “Bodhidharma” (2015) and “Bodhidharma, Still There” (2015) can be taken as a pair (even though they are not arranged as such in the gallery): one directly depicts the sitting Buddhist monk; the other illustrates his existence despite his absence from the painting. Similarly, Zeng’s massive “Laocoon” (2015), a portrait modeled after the ancient Greco-Roman sculpture “Laocoon and His Sons”, is a commentary on the impermanence of man’s efforts expressed through the merging of mediums and styles. To the casual viewer, however, this is lost, again giving way to Zeng’s works’ resemblance to Western models.

Zeng Fanzhi, “Paintings, Drawings and Two Sculptures”, exhibition view. Artwork © Zeng Fanzhi Studio. Photography by Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

曾梵志,”油画、素描和两件雕塑”,2015,展览现场

Zeng’s thoughtful articulation of complex networks of philosophical and visual tropes stands in contrast to Gagosian Gallery’s methods of display. Rather than Zeng’s layered imagery and meanings as a point of entry for deeper engagement, Gagosian arranged his works by their size, color, and subject matter. Large-scale landscapes remained together; Zeng’s “Self Portrait” (2013) was placed across from his image of the seated Bodhidharma, and his classically inspired works appeared alongside one another, transformed into a “who’s-who” of historical masterpieces rather than a critical reinterpretation of them. Instead of being in conversation with one another, each work came across as a different version of the same piece, with the method of display beckoning the viewer to choose their favorite painting based on color scheme or on whether they want a monk, seated man, or young girl in their painting. Rather than feeling like a dynamic curated space, the vast white cube became a showroom for new art.

Zeng Fanzhi, “Laocoon”, oil on canvas, 400 x 400 cm, 2015. ©Zeng Fanzhi Studio. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

曾梵志,《拉奥孔》,2015

Nowhere was this strategy more apparent than in the northern salle of Gagosian. On opening night, amidst the throngs of hundreds of gallery-goers, viewers waited behind velvet ropes to enter a narrow, dimly lit room. Contained inside was Zeng’s Untitled series (2009–2015) (mixed media on paper paintings) and one of his two Untitled (2014) cast silver branches. Set alongside wooden tables dating from the Ming dynasty and accented by Song-period scholars’ stones from the famous Jiansongge collection (which had been auctioned-off by Sotheby’s in 2008), the objects worked together to emphasize Zeng’s “Chineseness”. With their elongated rectangular shapes and soft, earthy hues, the pairing also seemed to suggest that the paintings were meant to appear as abstracted classical Chinese scrolls. That, together with the low-light environment, gave the room a sense of mystery in contrast with the bright, sterile whiteness of the rest of the gallery.

Would a Western artist be given such treatment? The display of East Asian art has always been mired in an array of confusing (if not deliberate) curatorial choices made by leading institutions, often compounded further by the limited expectations of Western audiences. Looking as far back as the Chicago World Exposition of 1893, East Asian nations were portrayed as exotic, their artistic achievements cast more as decoration than as a critical response to the historical and cultural forces that shaped them. While this led to a popularization of Asian art and to the appropriation of artistic forms, it also led to its marginalization, domestication, and commodification in the West. Most notable was then Chicago-based Frank Lloyd Wright, who borrowed heavily from Japanese art and architecture (seen in the adoption of low, horizontal lines, open floor plan, and interior design exhibited in his Robie House in Chicago’s Hyde Park (1909) and the Asian-aesthetic of his perspective drawing of Thomas P. Hardy House, Racine, Wisconsin (1905). In an interesting historical turn, Wright even went on to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1923)). Similarly, designers like Louis Comfort Tiffany adopted many visual forms from Japan and China, as displayed in his stained glass works and metal filigree, then popular items with the American elite to furnish their homes. As framed by the Chicago World Exposition, Asian art was something to be enjoyed as complementary to the homes and lifestyles of the Western inhabitant.

Zeng Fanzhi, “Blue”, oil on canvas, 400 x 700 cm, 2015. ©Zeng Fanzhi Studio. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

曾梵志,《蓝》,2015

Even today, this occurs with Chinese contemporary art. Examples of it can be seen throughout museums in the United States. Upon exiting the recent (touring) exhibition of the Rubell Family collection, “28 Chinese” at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, a large bulletin board asked audiences which piece of art they would like to take home, implying a highly static human-to-object relation. Similarly, “China Through the Looking Glass”, a recent collaboration between the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute and Department of Asian Art, was positioned as an exploration of “the impact of Chinese aesthetics on Western fashion and how China has fueled the fashionable imagination for centuries”. The Met went on to note that “the West has been enchanted with enigmatic objects and imagery from the East”, stating that “our visions of China” were framed by popular culture and cinema.(1) Needless to say, the viewer is left to assume whose vision this represents and what messages are being conveyed when words like “enchanted” and “enigmatic” are used to contextualize costumes created by Western fashion designers placed next to ancient Chinese art.

Zeng Fanzhi, “This Land so Rich in Beauty No.1″, oil on canvas, 250 x 1,050 cm, 2010. ©Zeng Fanzhi Studio. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

曾梵志,《江山如此多娇》,2010

In his 2002 book Why Are Artists Poor? The Exceptional Economy of the Arts, the artist and sociologist/economist Hans Abbing states that “turning a work of art into a commodity can lead to its ultimate destruction”.(2) In this light, since there is no quantifiable measure for art’s beauty or function, it remains useless to a market until it is turned into a non-art commodity.(3)Today, as contemporary art and its collecting has become a proxy for capital exchange, artworks’ original meanings are lost and the artist often remains outside the satellite economy that their talents fuel. Galleries such as Gagosian become the highly effective point of sale, acting as both brand managers and merchandisers of art and artists, all the while applying the veneer of a museum alongside the strategies of a commercial showroom. With one hand, they help to inform their audiences about what is new; with the other, they add to the speculation of art by increasing its prestige through provenance. For Chinese contemporary artists like Zeng Fanzhi, this means having his work set next to Chinese antiques, suggesting that both are status symbols (to both Western and Chinese collectors), as well as objects of commercial value.

(1) “China Through the Looking Glass.” China Through the Looking Glass. Web. 5 Dec. 2015. <http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2015/china-through-the-looking-glass>.

(2) Abbing, Hans. Why Are Artists Poor?: The Exceptional Economy of the Arts. Amsterdam: Amsterdam UP, 2002. p. 42.

(3) Abbing, Hans. Why Are Artists Poor? p. 44.