This review first appeared in Ran Dian Issue 2, Winter 2015-16.

“Attacking The Boxer From Behind is Forbidden”, Li Liao solo exhibition

Klein Sun Gallery, New York, Oct 14–Nov 14, 2015

In his performances to date, Li Liao has addressed himself to different environments, exchanging his own presence for outcomes either planned or undefined from the outset. He has been content to place himself directly, and sometimes painfully, in public situations, often seeming to relinquish agency for the sake of experiment.

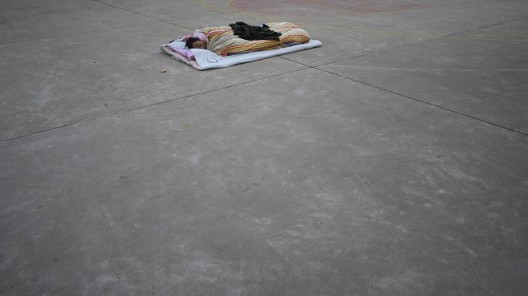

Five years ago in Wuhan, Li waited for a stranger he had met on the internet to come to a designated public place and slap him in the face as he stood with eyes closed. The following year for “Single Bed”, he fell asleep in a playground, by a lake, outside a shopping mall and by an ATM machine, staying there until he woke up or was disturbed. “Weight Loss Plan” meant covering a month’s worth of food, phone bill and transportation with only 350 RMB in 2011 (something he had also done a decade before for the same amount). He locked himself to the railing of an office building for a day (“Spring Breeze”, 2011). “Art is Vacuum” (2013) meant giving the 50,000 RMB production budget for his work for the Hugo Boss Art Award show to his girlfriend’s father to compensate for having no better occupation than being an artist. Li’s best-known (and most easily legible) work is “Consumption” (2012), for which he worked at Foxconn in Shenzhen for as long as it took to earn enough to buy one of the iPads for which he had been on the assembly line. (The piece, displayed by way of his old Foxconn uniform, ID card and the iPad, featured in the 2015 New Museum Triennial to much acclaim).

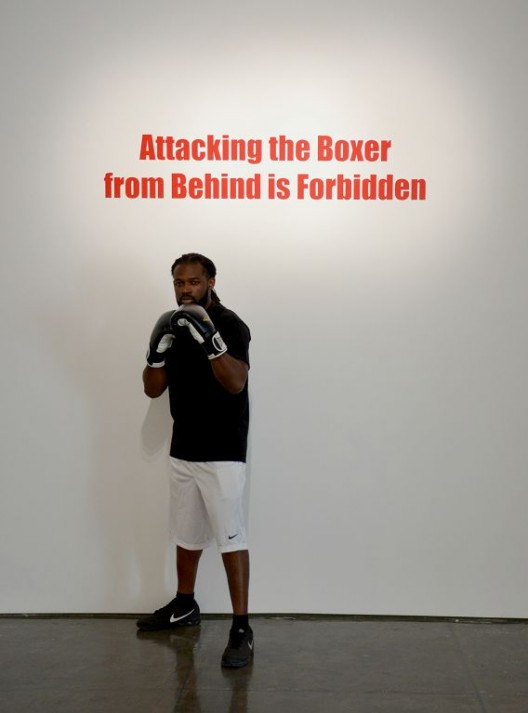

The focal piece in Li Liao’s recent solo exhibition in New York (his first in America) did not fit squarely with either of the main tendencies evident from his previous works—resigning himself in public, or actions to do with local or global socio-economic capital beyond the art world. A professional boxer awaited visitors to the gallery, against whom he would defend part of the space with his gaze and postures as if it were the ring. The title of the piece (also of the show) was printed in red letters on the wall behind the mercenary actor: “Attacking The Boxer From Behind is Forbidden.” The idea was ostensibly to “complicate one’s sense of expectation” of a commercial place and to introduce tension there. That the situation was thus explained in the press release begins to suggest the conflicting strands of this piece, its intended and unintended effects and inversions.

李燎,《严禁从背后袭击拳手》,展览现场,2015

Li Liao, “Attacking the Boxer from Behind is Forbidden”, installation view, 2015

This was the first time Li Liao had substituted an actor for himself for one of his performances. Where Li slept in public places, the artist was absent here; the act, acted. At the opening, the limitations of performance as a challenge of managing a staged interactive (or reactive) encounter made themselves plain as the boxer strived to maintain a menacing expression; individual visitors approached him unthreatened, smiling shyly. Despite an aim to heighten the tension inside the white cube of a gallery—most often tied to a feeling of intimidation as people assume they will not understand what they see or because they are in rarefied display environment whose real purpose is accessible only to the few—the performance inverted its own intent. Suppressing slightly their mirth or curiosity, visitors empowered by the atmosphere of the gallery and the innocuous event of an opening were unperturbed by the boxer on his empty turf. At play, too, was the prevention of actual contact in this performance—that the boxer couldn’t touch the visitors, and they were told not to attack (implicitly, even approach) him from behind—maintained a purely hypothetical atmosphere. For comparison, one could consider a recent piece called “The Count” by the British artist Demelza Watts, wherein upon entering the room, the visitor is given a countdown by a boxing referee before being asked leave by a surly bouncer, who will escort them out if necessary. Without the threat of contact, Li’s performance remained in the ring of hyperbole, his boxer “domesticated”.

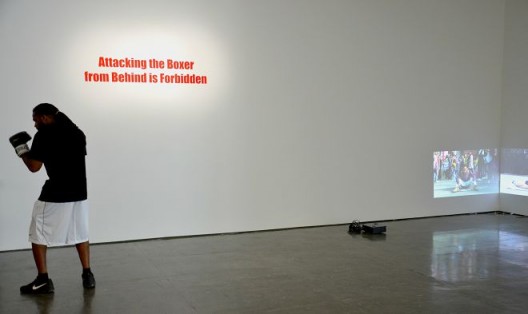

李燎,《严禁从背后袭击拳手》,展览现场,2015

Li Liao, “Attacking the Boxer from Behind is Forbidden”, exhibition view, 2015

Expectation, which the performance purports to complicate, is already complex in a gallery—especially when one has been a told a performance will happen. Commercial galleries are strange places somewhere between the private and public realms; art’s illusive relationship with value makes for an unclear space. What’s more, viewers anticipate something to react to, as well as their own reactions. The other works on show by Li Liao at Klein Sun served as a reminder of the fact that performance as an experimental art form secures or risks a great deal by its choice of context. Unlike sticking to a budget (like “Weight Loss Plan”), “Attacking The Boxer From Behind is Forbidden” has no clear goal. Its cause and effects are both fueled and restricted by the gallery context. Watching “A Slap in Wuhan” and “Single Bed”, both similarly open-ended works but for which there was no expectant audience, only a passing public, and where the surroundings were ordinary and unassuming, one is reminded of the value of anonymity for experiment. “Attacking The Boxer From Behind is Forbidden” both depended on and was deflected by its surroundings. The performance hovered, physically and conceptually, in a constant, sparring state.

Li Liao’s boxer was there every day until the show closed. Unwittingly, perhaps, this work tapped into a seam of empathy running through Li’s work—a sort of concentric vulnerability might connect this lone boxer in an unfamiliar environment with an artist bedded down on the street. “Attacking The Boxer From Behind is Forbidden” evoked more than had been imagined for it.