Chambers Fine Art (Red No.1-D Caochangdi Chaoyang District Beijing 100015), until Nov 20, 2016

“Dusty Landscape” is what I call an unexpected surprise. In the gallery’s right-hand space, instead of the kinds of topics, media, and aesthetic one might have become used to amid the Beijing art scene, one is confronted by a personal and refreshing angle on how to approach both contemporary art and “images.”

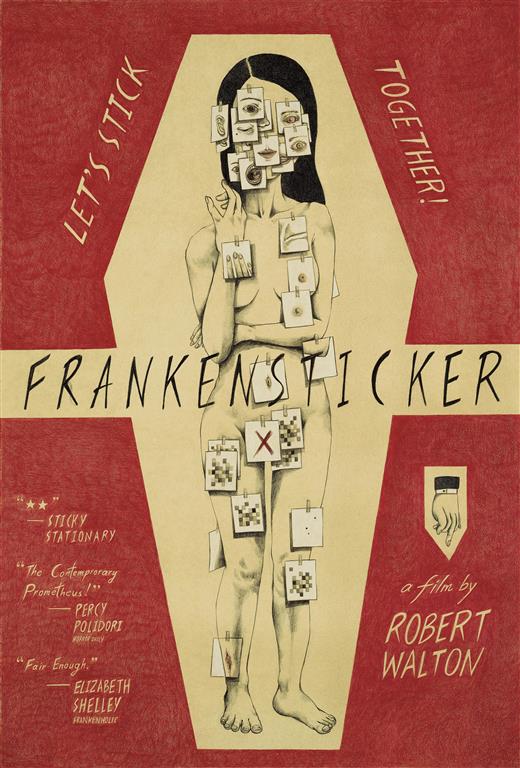

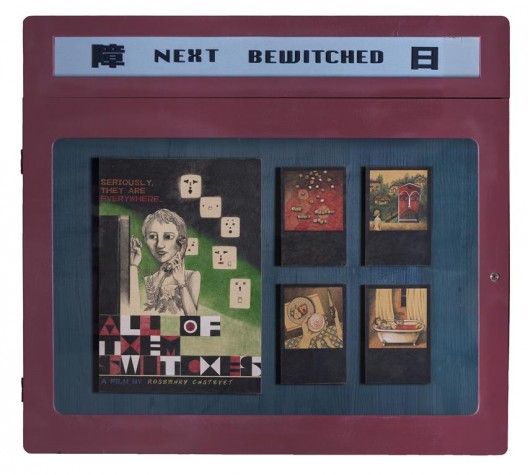

The Hong Kong artist Ho Sintung—who is known for opting to work on a small scale and for using simple materials and traditional media such as pencil drawing—has filled the gallery space with a reflection on her private passion: cinema and movie posters; quietly, this unveils further levels of meaning. The fact that film posters are neither a hot topic for contemporary art nor a contender for originality among other globalized trends in visual culture is already a pleasant surprise.

Ho Sintung loves cinema; she loves old movies, vintage movie posters, and old movie theaters in a personal way, with attention to their aesthetic aspects, but also the social and political ones. For this show, she has invented a series of hand-drawn posters for imaginary horror movies. These are displayed in the metal boxes typical of old Hong Kong movie theaters.

Each of the hand drawn posters is an original artwork, an appropriation of a well-known aesthetic form, a quote from a certain period (some might remind Italian neorealism, Hollywood noirs or spaghetti Westerns, for example) and an exercise in imitation and imagination. Ho’s pencil work and technique are highly sensitive and skillful without being narcissistic or “precious” because they do not stand alone, but serve a smart and provocative conceptual purpose in which humor and unpretentiousness walk hand in hand with discipline and care.

I also think Ho Sintung’s interest in horror movies is an intelligent and subtle one when it comes to choosing a different path (that is, from those commonly seen in the art world) in order to address contemporary social and political issues. She understands how horror movies are experienced both subjectively and socially; for example, they often occupy an important phase of our adolescent life in which abjection, lack of confidence, anger, and fear accompany the daily experience of reality, bodily transformation, and imagination in both the private and public spheres. The special pleasure in the mix of transgression, fear, and disgust these films evoke and celebrate can often be a vehicle for teenagers to transpose deep insecurity and a sense of inadequacy, as much as they can simply be a refuge in which the sudden realization of the horror vacui of existence takes the shocking but more bearable forms of imaginary monsters, zombies, and killers.

Besides this, horror movies are a popular form, the cultural references of which bounce between science-fiction doomsday scenarios and ancestral/ancient superstitions, between social and religious dogmas, myths and urban legends. Their visual forms come from art and design as much as from comics or from carnival, and from old sacred iconography as much as from the profane.

Ho Sintung perceives how horror movies, in their own way, can activate history by interconnecting past, present, and future nightmares in their grotesque but accessible and popular manner. For her posters, she invents horror movies dealing with mass poverty, inequality, authoritarian state abuses, and other sensitive references. Through these, she responds to reality as an artist, as a woman, and as a Hong Kong citizen showing in mainland China. Moreover, she seems to suggest, similarly to what happens in science fiction, that the different clichés presented by horror movies often change with time, and from being perceived as trash or low culture in the moment they appear, they can in hindsight seem prophetic.

If their distance from high culture, high art, and high literature always worked as a guarantee for horror movies to be democratic and available to anyone (and even, to a certain extent, to bypass censorship), looking at Ho Sintung’s sophisticated but firm attempt to introduce them, in the partially disguised form of personal fixation, into contemporary art, can also be interpreted as a suggestion about how art can engage with a larger audience on important topics using humor and a relatively traditional visual approach instead of the often mannerist and repetitive language of pure avant-garde contemporary art.

Contrary to a lot of contemporary art which ends up as simply a “comment” on reality, this exhibition offers an elaborate but still accessible and unpretentious imaginary journey that makes us “look” and “think” (and even “enjoy”). The artist achieves this not through some sort of shock, but via a conscious desire to establish intriguing and intellectually provocative communication with a larger public using a re-invented visual language that is nonetheless familiar.

Beyond this already rich level, however, the show continues in the small, dark room next door, where an installation pays homage to Pierpaolo Pasolini with a remake of the carpet from the infamous film The 120 days of Sodom occupying the whole floor and small painted portraits of both the victims and the butchers from the movie hanging on three of the walls.

After seeing this room, I realized that the show can be read and felt as a complex allegory about cruelty and its contingency to human beings, history, and culture. Richard Rorty, in one of his analyses of the distinction between the public and private, suggests distinguishing between books that help us to be more autonomous and books that help us to be less cruel.

Perhaps when artworks, as in this case with Ho Sintung, are so articulate and sensible, and not self-reflexive, they have the potential to help us in both ways: by fostering individual autonomy through reflection on the idiosyncratic fantasies which artists and non-artists who attempt autonomy spend their lives reworking, and by helping everybody to notice the effects of our actions on other people, and trying to prevent cruelty.

Christian Lemmerz & Norbert Tadeusz: “Meat”

Faurschou Foundation (798 Art District, No2 Jiuxuanquao Road P.O.Box 8502, Chaoyang District Beiing, China 100015), until Dec 15, 2016

Faurschou had to deal with censorship; it did so brilliantly. The exhibition planned in Beijing for the sculptor Christian Lemmerz and the painter Norbert Tadeusz was not approved by the authorities, who prohibited the display of Tadeusz’s Meat series.

These paintings, in which a sense of space and composition (this can remind one at times of David Salle, Francis Bacon, or even Otto Dix) are associated with a strong but composed expressionist-realist palette, and a subject—meat—in which the representation of human and animal bodies as a paradigm for torture, sexuality, abuse, decay, and all their connected symbolism, in a very direct and even didactic way, continue the iconography and the tradition of such images, from Chardin to Rembrandt and from Soutine to Bacon. Tadeusz re-arranges and re-interprets these with an attitude which, instead of being concerned about the new, assures continuity by repeating the references over and over in an obsessive and methodical way.

What the authorities found subversive or dangerous in these paintings it is difficult to tell. For sure, the current leadership is paying a lot of attention to art and images of any kind and in any medium, but still the content of the paintings does not directly criticize China; rather, it reiterates a long dialogue with the history of art and, to be precise, with the history of Western Art. Is the epic of the flesh exposed too much of a burden for the government? Is the naked body and anatomic representation and symbolism always too much for Asian sensibility (let’s remember Francois Julien’s book Le Nu Impossible—The Impossible Nude—on the subject of how the concept of the body, and, as a consequence, the “nude” in art never made sense anatomically in Chinese philosophical, aesthetic, and cultural traditions at large)? Or is it about the palette, which lies between a controlled but nonetheless bold expressionism, and which might have quite a disturbing visual and sensorial impact? Or is it for the “violence” and the sense of lawlessness and danger which the works can communicate? Who knows—perhaps it was all three, or something else….Or maybe simply because this kind of work is, first and utmost, non-consensual.

My guess is that Tadeusz’s carefully composed series resonates too much with the Western history of art, with its depiction of the artist as an edgy individual dealing with the uncanny absurdity of life as ultimately being composed of pain, flesh, and violence. The irrationality and the irreversibility of this statement (still embedded in the heritage of the two world wars, from Nietszche’s Human, All Too Human to Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night) is too much, because it is too far from Chinese culture and nature? Or instead, is it too much because it mirrors the violence which Lu Xun, Lao She, and other great connoisseurs of the Chinese soul have brought up in their novels, rhymes, and essays? Or perhaps the specter of the recent past is still too close and too consciously repressed to take the risk of exposing them to these images and to what they can do to the collective unconscious? Who knows.

The bulky, slightly stiff, but powerful marble sculptures of Lemmerz, in which animal and human body parts intersect each other in an intrusive and willingly ungracious way have been allowed into the space, but not the colorful meat paintings. Why? Is white marble not as dangerous as strong emotional color?

The Fauschou Beijing team, then, while accepting the ban, with an articulate text (available for visitors), explain how they cannot accept it fully because in this exhibition, as in every other one they have done, there was never the intention to engage in a political confrontation with the leaders of this country which hosts them, but only the will to display art of the best quality and to it available to the Chinese public. As a consequence, all the canvases which should have been on the walls of the Beijing space have been replaced by an exact number of white canvases with the same dimensions as Tadeusz’s originals, while the original ones are being exhibited in Hong Kong.

In Beijing, Lemmerz’s white marble sculptures are surrounded by the ghostly empty double of Tadeusz’s paintings; in the back of the space, a couple of Tadeusz’s drawings are displayed anyway. The rest is a surreal, silent dialogue between the sculptures and the paintings that should have been there.

There is something wrong now in the show that we all feel without necessarily knowing all the details. The Faurschou team’s response to the government’s censorship has been smart, witty, and provocative as an artistic intervention. Instead of canceling the show, they have decided to present the public with the version “co-curated” by the local relevant authorities, leaving the refused half of it available in that “part” of the “one country”, which, so far, is supposed to follow the second of the “two systems”. A schizo-exhibition for a schizo-country. Hats off!

Christian Lemmerz & Norbert Tadeusz: “Meat”, installation view at Faurschou Foundation, Beijing. Photo: Jonathan Leijonhufvud

Christian Lemmerz & Norbert Tadeusz: “Meat”, installation view of Faurschou Foundation, Beijing. Photo: Jonathan Leijonhufvud

Ink Studio (Red No. 1-B1, Caochangdi, Chaoyang District, Beijing, China), until Nov 20, 2016

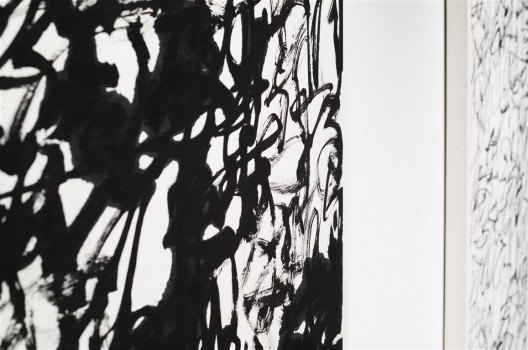

Ink Studio presents us with an epic celebration of experimental calligraphy master Wang Dongling’s quest for the possibility of gestural paintings using traditional Chinese shufa.

After decades of study and practice, construction and deconstruction, conceptual interrogation and intuitive initiative, this elegantly aging man has created a body of work that is impressive in its size and energy, yet with a relatively humble and unspectacular attitude. The works are an endless dialogue between the form and the formless, re-elaborating all possible trajectories, experiences, and context in which calligraphy dances with informal painting.

Along this path already explored by a large number of artists (perhaps even too many), Dongling succeeds in adding a little more by never indulging in self-celebration or preciosity. Even when his performances, which we can appreciate form the videos also on display, show how his reputation and fame push him towards the theatrical and the “staged”, this man maintains simplicity, respect, and a touching intimacy in the act of writing/painting his huge works which is quite poignant.

I particularly appreciated those in which his dialogue with chaos becomes so compelling that the scribbling overlaps again and again so that any potential aesthetic bliss or “beautiful” effects are dropped, allowing us to just to watch the obsessive gesture finally dissociated from most external concerns.