December 22, 2018

by Silvia Pease

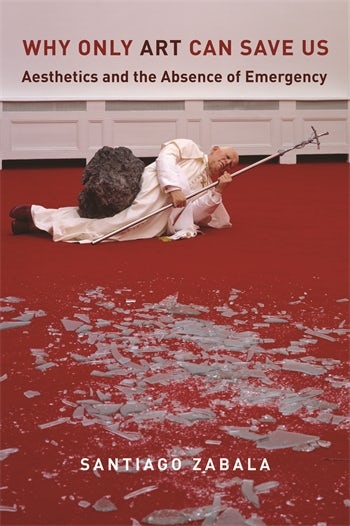

Since the time of Plato, philosophers have conceptualized utopian societies based on ideals of justice. Hence, Plato, himself, assigned the philosopher-king this existential responsibility. During the medieval period, St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas searched for methods to improve the existence of their societies. And, in the 19th century, Karl Marx describes politics in scientific terminology through his “materialistic interpretation of history.” Hence, throughout history, we find ourselves searching for ways to nurture empathy and justice to cope with the political world crisis and improve our lives. The book, Why Only Art Can Save Us, written by a contemporary philosopher and author, Santiago Zabala, questions how the creation of art can shift the reasoning and existential being of humanity; and how art could be the only salvation to the political world crisis. Thus, Why Only Art Can Saves Us, is a philosophical, political, and existential reflection on the appeal and aesthetic qualities of art in the 21st century.

Santiago Zabala, Why Only Art Can Save Us: Aesthetics and the Absence of Emergency, (Columbia University Press, 2017), 198pp.

圣地亚哥·扎巴拉,《为什么只有艺术能救我们:美学及紧迫感的缺失》,哥伦比亚大学出版社,2017,共198页。

Zabala starts his book by saying that our societies experience “emergencies that we can no longer afford to overlook if we care about our social, urban, environmental, and historical salvation.” His idea, of art as a cognitive influencer “whose time has come,” proposes an emphasis on a subjective approach to art and aesthetics.

Inspired by Heidegger, Zabala addresses “the emergency of the lack of emergency” by stating that our world is impaired by our inability to recognize our absence of “Being.” This provocative statement is the core of Zabala’s thoughtful interdisciplinary approach to using art as a catalyst. So, to present his argument, he simultaneously explores the connection between the deprived era of globalized capitalism, and the proclamation of a unique and absolute truth, resulting in a shift of consciousness.

Furthermore, Zabala delineates an imaginative method of art creation in which the theoretical and political views direct the inquiry of our “comfortable existence,” and the attainment of our “genuine appearance.”

Zabala argues that salvation through art implies the exposure of the Being’s ontological condition to those politically aware and receptive. Hence, art is a process in constant renewal causing “alterations,” and it also “produces disruptions, requiring interpretations, response, and intervention instead of contemplation.” Consequently, to discover “the truth itself,” we must practice immediate self-reflection to fix the “leak” [In German, zeitgeist] in “our world view” [Weltanschauung] (Zabala, 111- 112 & 23).

His theory of emergency aesthetics points to the work of contemporary artists who address, in their artworks, issues of environmental and climate change, genocide or ignored histories, financial meltdown and technology crisis and the “lack of emergency” in art. Thus, Zabala contends, that these artists use imagination, concept, and politics merge to create the human experience of an individual living a meaningful life: kennardphillipps, Jota Castro, Filippo Minelli, Hema Upadhyay, Wang Zhiyuan, Peter McFarlane, Nele Azvedo, Mandy Barker, Michael Sailstorfer, Kardy, Alfredo Jaar, and Jane Frere. Their artworks, as per Zabala, have shifted “beyond aesthetic representationalism and formalism both because of their post-metaphysical philosophical positions and because they are affected by art’s current ontological appeal” (Zabala, 7).

Wang Zhiyuan, Thrown to the Wind, 2010, steel and plastic bottles, 400 (diameter) cm x 1150cm. Courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Collection, Sydney.

王智远,《龙卷风》,2010,金属、塑料瓶,400cm(直径)x 1150cm。图片版权为艺术家和白兔美术馆(悉尼)所有。

Wang Zhiyuan, Thrown to the Wind, 2010, steel and plastic bottles, 400 (diameter) cm x 1150cm. Courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Collection, Sydney.

王智远,《龙卷风》,2010,金属、塑料瓶,400cm(直径)x 1150cm。图片版权为艺术家和白兔美术馆(悉尼)所有。

The sculpture of Wang Zhiyuan, Thrown to the Wind, 2010, is an example of an artwork that pushes us into a state of emergency. It consists of a thirty-six-foot metal framework in a shape of a tornado, covered by the surplus of plastic containers and bottles, depicting a capitalistic society, Beijing, and its discards. Besides the aesthetic intensity of this artwork, it bares the emergency behind the accumulation of plastic that will never decompose. Zabala writes, “The alteration Zhiyuan creates through his sculpture thrusts us both into the overwhelming fact of the plastic bottles and their environmental consequences” (Zabala, 57).

If we accept his proposal, Zabala concludes that “the truth of art no longer rests in representations of reality but rather in an existential project of transformation.” He states that art will shock and confront the viewer, who in turn, will analyze, choose, or revise his or hers socio-cultural-political dominant world view.

Zabala’s Why Only Art Can Save Us aims at the existential claim of art. Meaning, he is declaring a democratic political praxis of great importance warning that those immersed in capitalism do not see the emergencies. For Zabala, the central focus in contemporary art should be the conceptual interpretation of the cause of the struggle and “lack of emergency” along with the loss of Being. While it is probably too early to declare this as the only way to art creation for the 21st century, possibly helps us to widen our scope in confronting the ever-changing world issues and the art creation and appreciation. A shift in art aesthetics towards an ontological argument of our historical existence seems to be a logical proposal for the art of the 21st century (Zabala, 7).

Originally published on the website of IDSVA( Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts)