Cao Fei

MoMA PS1 (22-25 Jackson Ave. at the intersection of 46th Ave. Long Island City, NY 11101, USA), Apr 3–Aug 31, 2016

Chinese artist Cao Fei knows the visual vocabulary of new media art, and her work shows a post-internet sensibility. But whether she “tackles the numbing state of modernity,” as per the title of Kathleen Massara’s preview of Cao’s MoMA PS1 solo show on Artnet, seems debatable. The difference between tackling and narrating is that of distillation versus mere storytelling, and the plain gesture of juxtaposing a minor group of Guangzhou cosplay enthusiasts with cranes at construction sites and migrant workers (the Cosplayers series, 2004) doesn’t really distill the essence either of societal change in contemporary China or “the numbing state of modernity.” Not to mention that to describe the state of modernity as “numbing” already sounds like an outdated simplification of something as loaded and unstable as the term “modernity,” and the constellation of socio-historical and epistemological complications it pertains to.

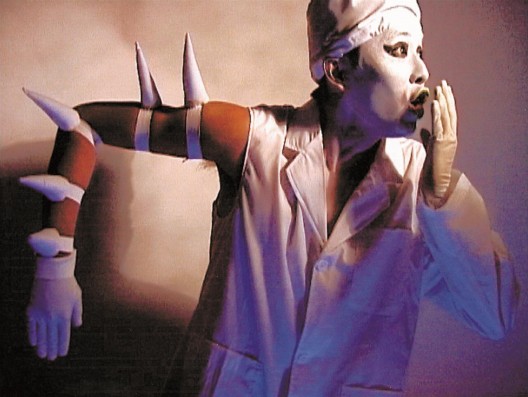

Dressing people up as Japanese manga characters and photographing them performing in different urban environments could be interpreted broadly as a kind of escapade into utopian fantasies, but how can we distinguish this form of entertainment from any other feel-good activity we engage with in our everyday lives? Arguably, there are subtler things we do that are more revealing of a post-modern mentality than literally acting out manga identities or doing weird dances in a factory space per the artist’s request; there is more identity fantasy at play in our daily interaction with and manipulation of social media profiles, for example, than walking around in a Sailor Moon costume once every year. In the same way, an amalgamation of famous Chinese urban structures into an “RMB City” (2007) doesn’t suffice to embody new China, and a post-apocalyptic zombie movie (“Haze and Fog”, 2013) doesn’t capture the uncanny feel of looming doom in the post-human everyday. New media art can have a disruptive effect by distilling contemporary life into a seemingly hip and fun visual vocabulary—it doesn’t stop at hip and fun, but finds that precise point where hip becomes absurd and fun becomes sarcastic. The way artists can re-appropriate mixtures of post-internet references has the potential to trouble what is taken for granted and reveal underlying tension and friction. Artworks that feel at once relatable and unfamiliar can invoke how post-human empathy and identity function.

Cao Fei, Cosplayers Series, “Tussle”, C-print, 75 x 100 cm, 2004. Courtesy of artist and Vitamin Creative Space

Isa Genzken and Ryan Trecartin, for example, tap into this feeling of the “unheimlich” wherein the juxtaposition of reality and fantasy, quotidian and absurd, social dominant and outcast is not overtly staged but intrinsic to a thoughtfully assembled “mess” of visual references. Trecartin’s works tend to have this intangible apocalyptic and surreal air; but unlike Cao, he doesn’t (need to) tell people overtly: this town is infected and this is the apocalypse. Interestingly enough, Massara quotes Cao’s disappointment at the lack of power she perceives in immersive artworks: “Art works [are] getting weak, [and] cannot grasp our real feeling anymore…Universal Studios theme park seems to be more perfect than all the immersive art works.” Is theme parks’ success over immersive art in captivating the attention of the general public due to their more perfect grasp of people’s real feelings? These also aren’t two directly and consciously competing forces. But surely, the difference between the theme park experience and the immersive art experience is that, instead of providing a smooth entertainment session that the participant soon leaves behind, immersive artworks should create an in-between experience that the audience navigates; this navigation, in turn, constitutes the substance of the audience’s immersion in and contemplation of the artwork or their experience with the artwork as a whole.

Cao Fei, RMB City: A Second Life Planning series, “RMB City: A Second Life Planning 05″, digital print, 120 x 160 cm, 2007. Courtesy The Artist and Vitamin Creative Space

“STRAIGHT OUT OF TIMES”, Cao’s performance at PS1 on opening day with The Notorious MSG, however, felt not unlike a theme park; it’s not enough to just throw a party with Chinatown hip-hop kids, dim-sum picture projections and cardboard images of super Chinese-looking signs and things if, as Barbara Pollack writes in the New York Times, Cao is trying to “encapsulate her country’s societal shifts.” True humor should capture the critical and tragic essence of a subject, but the party at PS1 was nothing more than lukewarm noise and fuzz. Massara mentions at the end of her preview that the artist immerses herself in the hip-hop community, but to say this is to completely overlook the tremendous social, political and historical richness that is hip-hop itself. There are most definitely intriguing anthropological implications to the phenomenon that a certain portion of young American-born Chinese tend to associate or identify with hip-hop culture more than other popular influences, but the question of how we might tap into the history and critical potential of this phenomenon needs perhaps a bit more digging than hanging out with a few Chinatown hip-hop kids and inviting them to a party at MoMA PS1.

“STRAIGHT OUT OF TIMES”, performance by Cao Fei and The Notorious MSG at the opening of Cao Fei’s retrospective at MoMA PS1, 2016. Photo: Charles Roussel

Cao narrates certain aspects of contemporary China and Chineseness, but again, there are two kinds of narration. You can either plainly describe something, or you can unpack and understand (or deconstruct) it and narrate it in a way that most strongly highlights why and how it is what it is. Underprivileged Chinese immigrants surviving in a suspended place called Chinatown may be a strange and telling global reality, but how do we narrate this reality in a way that can actually show the hows and whys, rather than just placing it in front of an audience? Sweatshops are terrible, and cosplay is unique, migrant workers suffer, etc.; we know this, and we might want the artist, or the critic, to take us one step further than a repetitive display of common apologetic knowledge and face value symbols.

We find certain paradigms in terms of how critics write about Chinese artists with a global presence today—or even the ways in which critics help build this global persona for Chinese artists. For example, the way Pollack tells Cao’s story is similar to how critics portray Ai Weiwei’s public persona. China is a wronging communist political regime and a non-Western periphery, and the artist is often an outcast in this already exterior location—he or she doesn’t fit into the general Chinese artist community. The family has usually been uniquely affected by the Cultural Revolution in some way, and the artist is usually rebelling against certain aspects of communist China under globalization, which then renders he or she as an acute embodiment of China today. This kind of narrated spectacle seems more judgmental than critical, more exotic than universally relevant and, most importantly, more alienating than inspiring. It is the type of old school narration that takes China as a passive victim of unidirectional globalization from the center toward the periphery, and which oversimplifies the manifold layers underlying transnational and cross-cultural social formations.

This retrospective didn’t speak substance, nor did the previews help. It would appear that many significant contemporary ideas and critiques are mentioned and presented, yet these are not analyzed or taken to critical levels that have been more carefully thought through. It all seems to be a self-sustaining cycle of face value symbols—in this sense, definitely numbing.

Cao Fei, “i Mirror by China Tracy (AKA: Cao Fei) Second Life Documentary Film – Machinima”, video still, 2007. The Museum of Modern Art, Fund for the Twenty-First Century.

Cao Fei, Whose Utopia series, “My Future is Not a Dream 03″, C-print 120 x 150 cm, 2006. Courtesy The Artist and Vitamin Creative Space