Yinka Shonibare MBE in Singapore

Yinka Shonibare MBE: “Childhood Memories”

Pearl Lam Galleries (5 Lock Road, #01-06, Gillman Barracks, Singapore), Jan 21–March 13, 2016

Gillman Barracks is a kind of ghost town, its 1930s colonial buildings separated by large swathes of grass, the ambient heat preserving the atmosphere like a mosquito in amber. Singapore is a place that likes to keep art tidy, so putting its art district in a former colonial military post and interning art galleries there where they cannot do any harm is eminently sensible. (1) The barracks was built in 1936 to accommodate an increase in the number of British soldiers stationed on the strategic Malacca Straits island. At that time, Taiwan and Korea had long been part of Imperial Japan and its “Manchukuo” puppet-annexation was 4 years old. In 1942, Japan invaded Singapore.

Once order was established, Japanese authorities set about imprinting Japanese culture on Singapore, a process known as Japanization, to erase Britain’s colonial legacy–the name was immediately changed from Singapore to Syonan-to [昭南島], meaning “Light of the South”…The Georgian calendar used by the Europeans was changed to the Imperial Calendar of Japan, which counts years from the traditional date of Japan’s founding in 660 B.C.E., so 1942 became 2602. The time zone was also altered so Singapore would be the same time as Tokyo… (2)

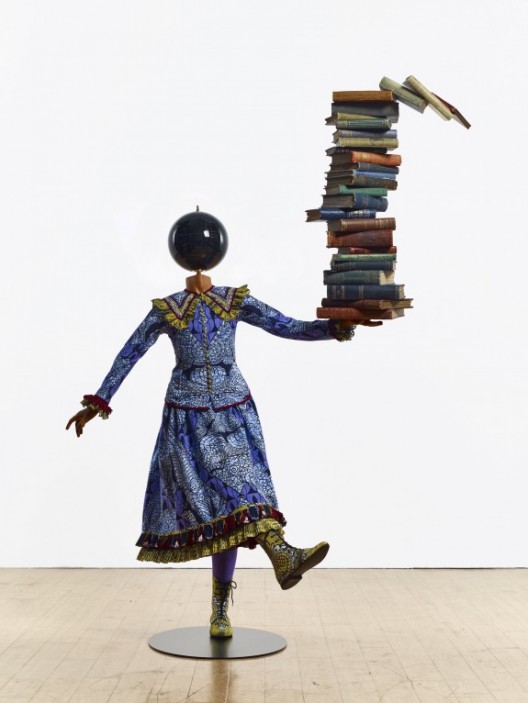

Yinka Shonibare MBE, “Girl Balancing Knowledge”, fibreglass mannequin, Dutch wax printed cotton textile, books, globe and steel baseplate, 179 x 139 x 8cm, 2015.

Colonialism always involves relativism: force, space and time travel. The Japanese remained in control until 1945. While power was returned to Britain, it was the beginning of the end for the Raffles colony and of Singapore achieving independence with Malaysia in 1963; it then broke away from the new federation in 1965.

In Gillman’s main building, Yinka Shonibare’s 2005 video “Odile & Odette” (2005) played in a dark, air-conditioned room. Two dancers—one white, one black, but with identical pink costumes—danced opposite one another a mirror-routine from Tchaikovsky’s 1875 ballet fairytale, Swan Lake; the dancers were separated only by a large gilt frame to complete the mirror illusion. The life-size installation causes the dream to leak into the gloom of the gallery. Will the good or the evil dancer step into the room? Which is which? In the ballet, Odile tricks Odette’s lover into breaking his vow of love. That such romantic cliché remains bewitching speaks to the powerful perseverance of our childish hopes and fantasies as much as cultural programming.

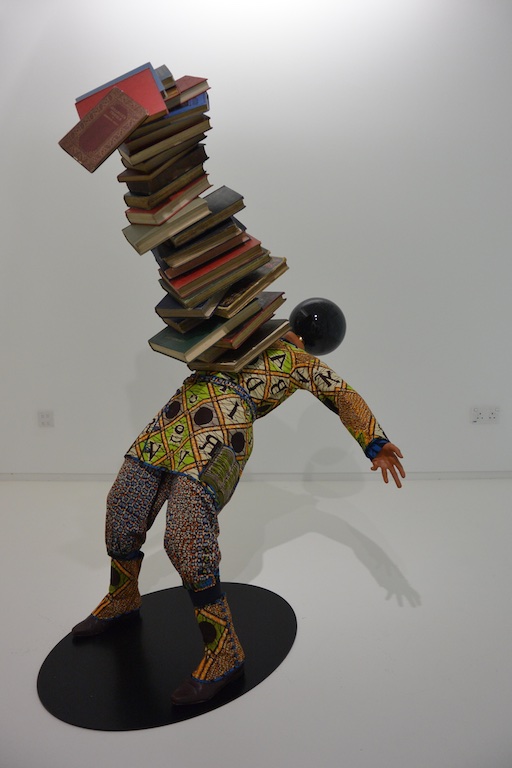

Yinka Shonibare MBE, “Boy Balancing Knowledge”, fibreglass mannequin, Dutch wax printed cotton textile, books, globe, leather and steel baseplate, 156 x 94 x 120 cm, 2015. (Courtesy the artist, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and Pearl Lam Galleries, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Singapore).

Emerging into the light and heat of midday Singapore, we walk down the road 100 meters to the main exhibition. Shonibare is perhaps best known for his “Gallantry and Criminal Conversation”, which was commissioned by Okwui Enwezor for documenta 11 in 2002. The Hogarth-ian tableau featured 18 headless figures, male and female, dressed in eighteenth-century costumes and having sex with (raping?) one another, or their servants, while a green, horseless coach flies over their heads. The finery is made of colorful “African” cloth, which is not actually from Africa—not “authentically” African—but bought by the artist at London’s Brixton market

Shonibare was born in London in 1960, moving to Lagos, Nigeria, when he was 3 years old. Aged 17, he returned to London to finish high school, eventually going on to study at what is now called Central Saint Martin’s, and then Goldsmith’s College. His hybrid position between different worlds—Western and African, England and Nigeria, emigrant and native—informs most aspects of his work; a prime example is his temporary commission for the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square, London, for which he decorated the sails of Nelson’s ship, HMS Victory, again with “African” cloth, and put it in a bottle (“Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle” 2010). It is identity art as id, where the id belongs both to the artist (personal) and the continuing, strange ripples of colonialism (political). Because identity is the primary path to approaching Shonibare’s work, there is another important aspect to note. Since aged 18 he has dealt with the effects of transverse myelitis, a disease that has left one side of his body paralyzed (his works are made by assistants under his direction). There is no need to dwell—it affects his body only, it does not embody him—other than to note that he is a sculptor, an artist interested in making forms in space. In the present exhibition are four colorful sculptures accompanied by a number of prints (which were unnecessary). The sculptures consist of two children riding a giant butterfly suspended from the ceiling, a boy and a girl each carrying piles of books in the midst of toppling over (juggling knowledge!), and a fifth child sitting under a giant hibiscus bloom. Each child has been decapitated, or rather each has had their head transplanted with a globe—heads full of dreams and maps. Until the democratizing effect of the French Revolution, decapitation was the special preserve of kings and queens. The guillotine was a most rational eighteenth-century invention, however: now anyone can be Royal.

Yinka Shonibare MBE, “Ibeji (Twins) Riding a Butterfly”, fibreglass mannequins, Dutch wax printed cotton textile, fibreglass, fur, leather and globes 265 x 235 x 105 cm, 2015. (Courtesy the artist, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and Pearl Lam Galleries, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Singapore).

This is the crux of the show, which by turns is intensely personal and political, involving paeans and monuments to childhood memories as well as echoing “songs of sorrow” for childhoods gone. So often are children’s picture-books morality tales, where ambiguity lies only in a parent’s lies and the paternalism of the forgetful, too busy using their ego to protect their ids.

The children play in their playroom; the dancers are in their music box. Outside sleeps a magical time machine where you can walk in the redundant grounds of a Nutcracker military. And beyond? Beyond Gillman is a neat, tidy, ostensibly multicultural, twenty-first-century logistics hub, where the new barracks are the classroom and colonialism has been replaced by takeovers.

Adventures in Colonialism – Part 2: Xue Song, will appear soon

Notes

1. Singaporeans take the view that art, in principle, is good and can even take place in public provided it doesn’t frighten small children, elderly aunts or the prime minister. The new National Gallery of Singapore was built so that high-school students would have somewhere to go on excursions besides an art fair. Still, it was pleasing to see so many high-school students at Art Stage Singapore. It is impressive that Singaporean parents apparently give their children enough money to buy art. Perhaps if they were slightly less generous, they could buy some too.

2. Abshire, Jean, The History of Singapore, Greenwood: Santa Barbara, 2011