“Landscapes in the Chinese style,” solo exhibition by Roy Lichtenstein.

Gagosian Gallery (7/F Pedder Building, 12 Pedder Street, Central, Hong Kong). Nov 12–Dec 22, 2011.

Like Cubism, Pop Art relied on two great talents who defined the movement for everyone else, contemporaries and followers alike. Roy Lichtenstein played Braque to Andy Warhol’s Picasso. Of the two, Lichtenstein was the quieter, more studious, and more conservative, but his blow-up reworking, refinement, and re-contextualization of mass comic book images established a form of grammar for how we have come to consume images and vice versa.

It was Warhol who raised Mao Zedong, or rather his “image,” from emblem of the People’s Republic to the pantheon of world images, transforming Communist propaganda into Capitalist consumer item. Prompted by his Swiss dealer, Bruno Bischofberger, to paint Albert Einstein because he was the “most famous person in the world,” (1) Warhol replied, “Oh, that’s a good idea. But I was just reading in Life magazine [March 3, 1972] that the most famous person in the world today is Chairman Mao. Shouldn’t it [sic] be the most famous person, Bruno?” (2)

The issue of Life was dated March 3, 1972 and commemorated Richard Nixon’s famous trip to China, the first by a U.S. president (while in office), which had taken place the previous week. The image of Mao that Warhol chose to reproduce was his official portrait rather than the photo on Life. Mao would join a gaggle of Hollywood stars and socialites, including Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, on Warhol’s portraits.(3) Warhol visited China just once, in 1982. A decade later, many Chinese artists — among them Wang Guangyi, Zeng Fanzhi, and Feng Zhengjie — began adopting and adapting (and critiquing) Warhol’s Mao in what would become Political Pop and Cynical Realism.

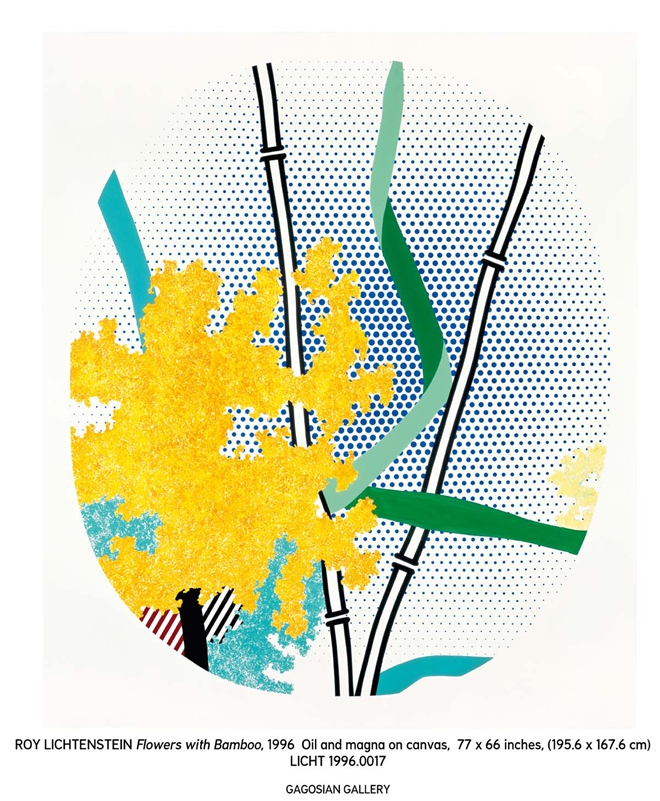

It was also during the nineties that Lichtenstein addressed, in his own way, the legacy of Pop Art in China. Landscapes in the Chinese Style would be one of Lichtenstein’s final series — he died in 1997, ten years after Warhol and the same year Hong Kong returned to China. The resultant paintings are not so much critiques of China’s “Literati” style but of its clichés. They include epic landscapes, evocative clouds, perfectly placed waterfalls, and curious scholar’s rocks — everything necessary to construct a literati artwork — all finished with Lichtenstein’s trademark appropriation of Ben-Day dots (as used, for example, in comic books) to create the “authentic” look of mass-produced graphic images.

For the first time since 1998 these works may be viewed in a dedicated exhibition, at Gagosian Gallery in Hong Kong. It is not the first time they have come to China — they traveled to the Hong Kong Museum of Art and the Singapore Art Museum in 1998. But since then a lot of water has passed under the literati bridge. The exhibition is therefore timely.

Gagosian’s press materials include this edifying quote from Lichtenstein:

I think [the Chinese landscapes] impress people with having somewhat the same kind of mystery [historical] Chinese paintings have, but in my mind it’s a sort of pseudo-contemplative or mechanical subtlety …I’m not seriously doing a kind of Zen-like salute to the beauty of nature. It’s really supposed to look like a printed version.