“Landscapes in the Chinese style,” solo exhibition by Roy Lichtenstein.

Gagosian Gallery (7/F Pedder Building, 12 Pedder Street, Central, Hong Kong). Nov 12–Dec 22, 2011.

Like Cubism, Pop Art relied on two great talents who defined the movement for everyone else, contemporaries and followers alike. Roy Lichtenstein played Braque to Andy Warhol’s Picasso. Of the two, Lichtenstein was the quieter, more studious, and more conservative, but his blow-up reworking, refinement, and re-contextualization of mass comic book images established a form of grammar for how we have come to consume images and vice versa.

It was Warhol who raised Mao Zedong, or rather his “image,” from emblem of the People’s Republic to the pantheon of world images, transforming Communist propaganda into Capitalist consumer item. Prompted by his Swiss dealer, Bruno Bischofberger, to paint Albert Einstein because he was the “most famous person in the world,” (1) Warhol replied, “Oh, that’s a good idea. But I was just reading in Life magazine [March 3, 1972] that the most famous person in the world today is Chairman Mao. Shouldn’t it [sic] be the most famous person, Bruno?” (2)

The issue of Life was dated March 3, 1972 and commemorated Richard Nixon’s famous trip to China, the first by a U.S. president (while in office), which had taken place the previous week. The image of Mao that Warhol chose to reproduce was his official portrait rather than the photo on Life. Mao would join a gaggle of Hollywood stars and socialites, including Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, on Warhol’s portraits.(3) Warhol visited China just once, in 1982. A decade later, many Chinese artists — among them Wang Guangyi, Zeng Fanzhi, and Feng Zhengjie — began adopting and adapting (and critiquing) Warhol’s Mao in what would become Political Pop and Cynical Realism.

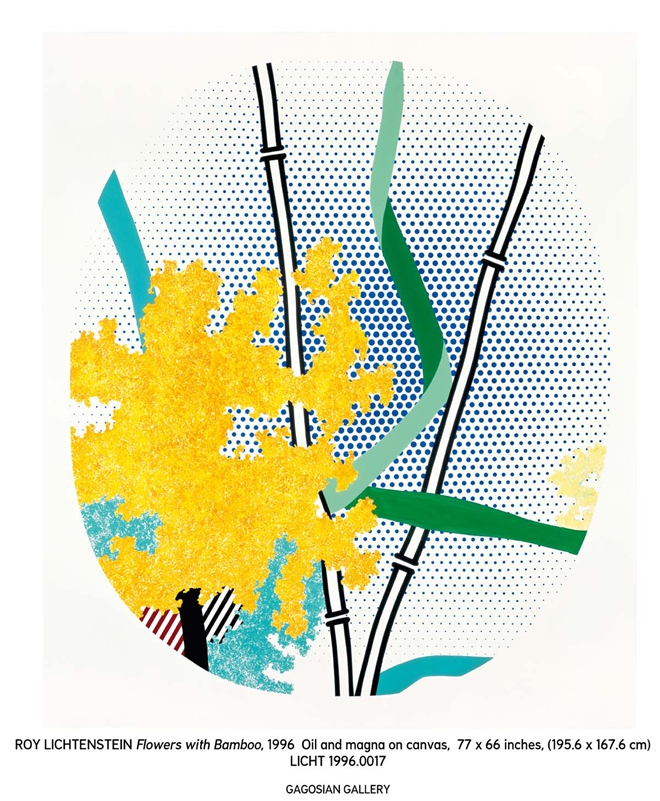

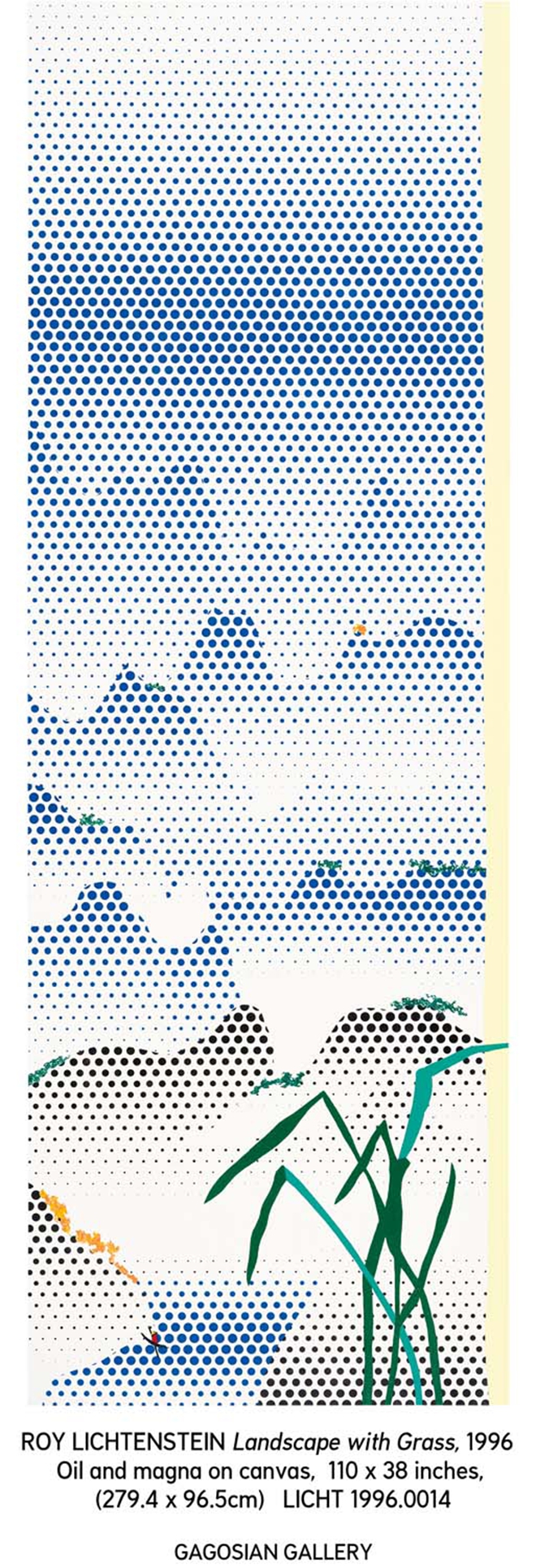

It was also during the nineties that Lichtenstein addressed, in his own way, the legacy of Pop Art in China. Landscapes in the Chinese Style would be one of Lichtenstein’s final series — he died in 1997, ten years after Warhol and the same year Hong Kong returned to China. The resultant paintings are not so much critiques of China’s “Literati” style but of its clichés. They include epic landscapes, evocative clouds, perfectly placed waterfalls, and curious scholar’s rocks — everything necessary to construct a literati artwork — all finished with Lichtenstein’s trademark appropriation of Ben-Day dots (as used, for example, in comic books) to create the “authentic” look of mass-produced graphic images.

For the first time since 1998 these works may be viewed in a dedicated exhibition, at Gagosian Gallery in Hong Kong. It is not the first time they have come to China — they traveled to the Hong Kong Museum of Art and the Singapore Art Museum in 1998. But since then a lot of water has passed under the literati bridge. The exhibition is therefore timely.

Gagosian’s press materials include this edifying quote from Lichtenstein:

I think [the Chinese landscapes] impress people with having somewhat the same kind of mystery [historical] Chinese paintings have, but in my mind it’s a sort of pseudo-contemplative or mechanical subtlety …I’m not seriously doing a kind of Zen-like salute to the beauty of nature. It’s really supposed to look like a printed version.

Clearly Lichtenstein was critiquing certain Western perspectives of China as much as the ennui of hackneyed images, Chinese or otherwise. But surely he was also making a statement about America’s relationship with China, China’s future, and also the status of his friend and rival, Andy Warhol, within this unique historical context.

The title of the series itself, Landscapes in the Chinese Style, should give pause. What style would that be? The catalog dutifully notes how Lichtenstein was informed by paintings from the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD) and also certain monochromatic prints of Edgar Degas, who, like so many Impressionists, developed a strong appreciation of Japanese and, to a lesser extent, Chinese aesthetics. (4) Lichtenstein visited exhibitions of East Asian art in New York, Washington, and Boston and perused various exhibition catalogs of Asian art, which according to Gagosian Gallery “may partly account for the emphasis on the secondary nature of his source imagery, deriving from reproductions of original works rather than from the works themselves.”

The works are not just reproductions of the Chinese Literati style presented in a formalistic manner. Pop Art’s critique of the Abstract Expressionists and their inarticulate emotiveness is in many ways equally applicable to the “true feeling” of Literati adherents, right up to the present day, however genuine such “feelings” may be. The Literati style, a once radical artistic movement cantered on a retreat to nature and personal contemplation, had become and largely remains a ragged lexicon of tired imagery — a mountain, a tree, a lake, a bird placed just so, with the moronic fastidiousness of an interior designer. Consider “Flowers with Bamboo” (1996). This is a huge work, in proportion with its heroic Abstract Expressionist antecedents but at odds with its Literati contemplativeness. And its blobs of yellow and stylized grass and bamboo sticks do conjure up Abstract Expressionism as well as any of Damien Hirst’s round splatter paintings, and with equal chutzpah and analysis. Whereas Warhol showed how all images were innately debased and celebrated the mundane as something transcendent, Lichtenstein warns us not to be complacent about images — they matter because they affect how you see the world, which is why, in his hands, the most trite speech bubble can become weighty. “Paintings in the Chinese style” ask us to consider what that means, what terms like “landscape” and “Chinese style” mean, not just from a Western viewpoint but also generally.

There are many extraordinary works in the exhibition that should not be overlooked because of their formal restraint. “Landscape with Grass” (1996) is simultaneously beautiful and very funny. Its title is simple yet self-important, like the grass blades themselves, plonked at the front, towering over the “charming” fisherman in his reed hat. The giant “Landscape with Scholar’s Rock” (1997) appears to incorporate Lichtenstein’s very same cast and painted steel “Scholar’s Rock” (1997), creating a discourse about reality and the philosophy of things. It would be nice one day to see these works exhibited with Zhan Wang’s own stainless steel scholar’s rocks, which also “reflect” on Literati limitations and weaknesses while simultaneously indulging in them (see his current show at the Ullens’ Centre in Beijing).

Most impressive is “Landscape in Fog” (1996). A mountain’s black silhouette is sandwiched between two ribbons of blue — sky and sea — themselves separated be a Willem de Kooning-like cloud-swirl of Expressionist paint that rips across the middle of the picture, tearing in two the restrained formalism of the Ben-Day landscape. Here I am reminded of Gerhard Richter’s photographs scraped over with paint. The intentions are really similar: to critically fuse two disparate traditions with an almost casual destructive gesture. Again Lichtenstein provides levity, with scant vegetation in the foreground, the prologue to the opera behind, and a twisted grasshopper-like tree with little tufts of jaunty color (apparently also the basis for one of the artist’s sculpture scholar’s rock in the exhibition). In some respects these jokes play the role of the speech bubble in Lichtenstein’s earlier works — “Whaam!” and “I don’t care. I’d rather sink than call Brad for help.” — only here the intention is not to punctuate but to deflate.

This is an important exhibition, one that has not received the serious attention it deserves. My few words here are but a short introduction to the subject. Warhol is only one side of the Pop story, while these late works from Lichtenstein are as eloquent an epitaph as one could wish for.

(1) Bruno Bischofberger is a storied Swiss gallerist, famous for bringing American Pop Art, Conceptual Art and Neo Abstraction to Europe, including artists as diverse as Warhol, Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenberg, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Bruce Nauman, On Kawara and Joseph Kosuth. His philanthropy over many years towards Artforum means that his kitsch, bucolic photos of Swiss village life now consistently and wryly decorate its back cover.

(2) G. Frei and N. Printz, eds., The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné: Paintings and Sculptures 1970–1974, Volume 3, (London and New York: Phaidon, 2010), 165.

(3) Warhol, an omnivorous media consumer, was probably aware of a weird 1952 photograph commissioned by Salvador Dali from the surrealist photographer, Philippe Halsman, which merged Mao’s official portrait with an image of Marilyn Monroe — another famous Warhol muse (the montage image was used for the cover of Vogue magazine in its December 1971–January 1972 issue — goodness knows why).