“Chinese Whispers. Recent Art from the Sigg and M+ Sigg Collections”, Kunstmuseum Bern and Zentrum Paul Klee (in dialogue with M+, West Kowloon Cultural District, Hong Kong, and Dr. Uli Sigg, in cooperation with the MAK Vienna), Feb 19–Sep 25, 2016 (extended from Jun 19, 2016)

“M+ Sigg Collection. Four Decades of Chinese Contemporary Art”, curated by Pi Li in collaboration with Uli Sigg and Lars Nittve, ArtisTree, Hong Kong, Feb 23–Apr 5, 2016

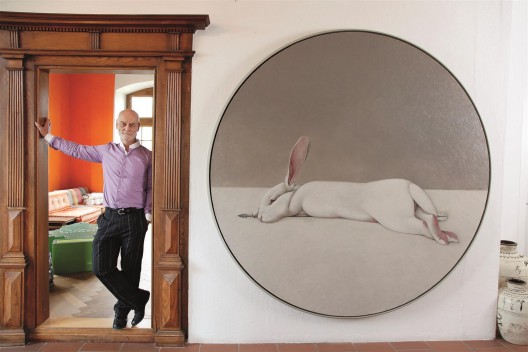

It is a curious historical fact that such a small and distant country as Switzerland has had such a profound impact on the development of art in China, especially at this moment of China’s greatest economic and cultural transformation. It is absurd. And yet without this bond, and specifically without the efforts of a handful of people such as Harald Szeemann, Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Lorenz Helbling and Urs Meile, what we have come to know as Chinese Contemporary Art would be an utterly different field. First among these, however, is Uli Sigg, the sinologist, diplomat, philanthropist, jurist, journalist, businessman, and collector—though he describes himself simply as a “researcher”. Sigg turned 70 this year, a milestone marked with two simultaneous survey shows of his collection, most of which he donated in 2012 to the new M+ museum in Hong Kong.

After studying commercial law in Zurich, Sigg became a financial journalist, including in East Asia. In 1977 he joined Swiss elevator company Schindler, moving to China with a handful of managers to negotiate and oversee the development of the Suzhou Elevator Company, the first joint-venture between a Western company and a Chinese State-Owned Enterprise. He met his wife Rita in the mid-1980s, marrying in 1989 (Rita leaves the collecting to Uli but participated actively in artist visits and also helped in translating many discussions). In 1990 Sigg took a sabbatical from Schindler but continued to be a member of the board until 1994, when he was appointed Swiss ambassador to China, Mongolia, and North Korea.

During his time in China, Sigg became an avid art collector—he already collected art, but his approach became more strategic and curatorial. At a certain point in the 1990s his development as a collector reached a tipping point, and he decided to collect the way museums collect: as a surveyor of the art of his time. He was no longer collecting for himself—he freely admits he didn’t like some of the works even—but on behalf of the Chinese people and of history. Sigg was collecting the art the Chinese government should have been collecting—if it had had the time, the opportunity, the resources to do so; if it had not been distracted by other things. If it had realized what it had. And appreciated it.

Sigg is still very much an ambassador for the art and artists of China. The China Contemporary Art Award he established in 1998 is the most important institution of its type in China, playing a crucial role in introducing international curators and museum directors to Chinese art, including the Swiss curator and art historian Harald Szeemann, the director of the 1999 and 2001 Venice Biennale (and former dOCUMENTA and Bern Kunstmuseum director); this led to Szeemann’s inclusion of 20 Chinese artists in the 1999 Venice Biennale. Sigg invented this unofficial role for himself whilst he was the Swiss ambassador (during which period he met Szeemann and reached out to others, such as Hou Hanru and Hans-Ulrich Obrist as they prepared their groundbreaking 1997–1998 “Cities on the Move” exhibition). While Sigg does not see himself as a model collector, this position has inevitably been forced upon him. He has set a standard for Chinese and Western collectors to emulate, even if quite often they fail to do so (the temptation to build edifices is seductive but perversely shortsighted, and China has more than a few zombie and ghost museums). Sigg’s is a more delicate and nuanced role than he receives credit for. He is as competitive and wily a collector as any, and fully aware of the capacity for his purchases to advance a career, promoting an artist to the art historical canon. Yet he is also acutely aware that circumstances have granted him a unique opportunity to help build knowledge about China and art, and furthermore to share those gifts both widely and generously. His choice of the word “researcher” is sincere.

Bern

Bern is a medieval walled city sitting on a slightly precipitous plateau in the neck of the River Aare. In spite—or because of—a profound bourgeois bent, the anarchist Bakunin died here in 1876, while Lenin sojourned here from 1914–1917. Established in 1879 in the center of Bern, the Kunstmuseum is the oldest art museum in Switzerland. Meanwhile, the Zentrum Paul Klee, founded following a donation in 1997 to Bern of 690 works by the painter’s daughter-in-law, Livia Klee-Meyer, is set among fields overlooking the cantonal city, some 20 minutes by bus from the Kunstmuseum. Designed by Renzo Piano, the world’s most prolific art museum architect, the Zentrum opened in 2005 and consists of airy halls beneath an undulating roof. The balance established between the two museums—of tradition and modernity, and physical distance itself—as well as between the more claustrophobic spaces of the Kunstmuseum versus the open ones of the Zentrum, provides a nice piece of dramaturgy (and over 4,000 sqm) for the display of some 150 works from the Sigg Collection.

The Kunstmuseum is a hushed temple to art (much attributable to the guards). Photography is forbidden! (A point we will return to.) In the catalogue preface, the directors Peter Fischer and Matthias Frehner comment that this first chapter of the exhibition “demonstrates how Chinese artists develop an artistic space between East and West, progress and tradition, that neither remains in the exotic or the provincial nor falls victim to global monotony”—which is worthy but also a very Western view: well-intentioned, but reliant on a Western rhetorical structure. This balancing act exists only in hindsight. The truth is that Western art history was consumed by China at one gulp, pillaged and ransacked like any other medium lying about an artist’s workshop. Sometimes the results were strange—perverse even—but also, frequently, exhilarating.

The selection of painting, sculpture, video, photography, and installation art was accordingly thoughtful, but the sheer diversity of the collection is difficult to unify conceptually. Individual artists were mainly left to themselves here, rather than being linked to wider narratives (aside from the aforesaid). For instance, Shao Fan’s deconstructed traditional chair, “Project No. 1” (2006) is nicely contrasted with his whimsical/serious “Rabbit Portrait Jiawu 1” (2014). However, some themes, such as nature and observation, do emerge, the former reflecting an ancient cultural thread and the latter a more modern one (and very popular in the West because it is relatable, and because it accords with certain Western preconceptions about China—just ask Ai Weiwei). On the theme of nature, the perspective is mortally anthropomorphic. On a stair landing appears Shi Jinsong’s beautiful and delicate but dead “Lock Pine Tree” (2011) while Shen Shaomin’s small, tortured “Bonsai” (2009), though once living, is now also dead (a younger version is greener). Meanwhile, Xiao Yu’s bent “Bamboo No. 5” (2010) could refer to Fred Sandback— “These three curves were the outcome of my study and interpretation of Bamboo as a line”—except it doesn’t: “By breaking the bamboo, viewers got a straightforward access to its spirit and strength” (as it says in the catalogue). Easy inferences are often false friends. This reflects how Chinese art of the past 30 years has often developed, sometimes informed by both Chinese traditions and study of the West, but very often with them running parallel rather than intersecting. The exhibition does not address this directly, and it is the elephant in the room—a great pachyderm, actually: why ignore it? But my comments are trivial. The sheer size and scope of the exhibition is overwhelming—would one attempt to review the permanent collection of Tate Modern or the Guggenheim?

Sometimes motifs are repeated, but not often. So while scholar stones appear in the work of Zhang Jian Jun, Shi Jinsong and, later in Hong Kong, with Zhan Wang, and abstraction appears to be as endemic to China as elsewhere, the broad swathe of works is strikingly dissimilar, which is how it should be. A visitor expecting yet more cynical realism would be advised to eschew their own cynicism, at least this time.

Painting is an obvious strength of the collection, whether conceptual (MadeIn/Xu Zhen, Yan Lei, and Zheng Guogu) or expressionist-pop (Ma Ke)—all born in the 1970s except Yan (b. 1965), or a witty mix of the two (Wang Xingwei). Liu Wei’s pair “Eastward” and “Westward” (2010), are electrifying Rosenquist-like meldings of pop and color field. Liu Ding’s installation “Products” (2005-6), a series of paintings executed by artists from the Dafen painting-factory village, incorporate identical favorite elements chosen by the artists—a tree, a pink cloud—and are all exhibited in gilt frames in a plush 19th-century red-walled salon. I was drawn more often to the photographic and film works, perhaps because they tend to be more raw, though no less mediated. Video artists Cao Fei and Chen Chieh-Jen are typical counterexamples. Like many artists, Cao employs humor and a surreal otherworldliness to slip us into an uncertain dream. Meanwhile, Chen Chieh-Jen uses reality to slip us out. A similar dichotomy can be seen when comparing the work, for instance, of Chen Wei or Jiang Zhi with that of Shi Guorui.

Let us go to the Zentrum. This chapter addresses rabid urbanization, environmental stress, historiography and hagiography and the individual (the first chapter probably did this, too). He Xiangyu’s deflated leather tank slumps on the ground (“The Tank Project, 2011–2013). Around a corner, his deflated Ai Weiwei lies slumped on the ground (“Death of Marat”, 2011). At the back of the hall some old friends are clattering about in their electric wheelchairs: Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s “Old People’s Home” (2007). As the comedian Stuart Mitchell remarked, “Why is it old people say ‘there’s no place like home’, yet when you put them in one …” This mad toy is one of the great works of the new century. Is that Arafat? Is that Marx? There are so many dead men in contemporary art and politics.

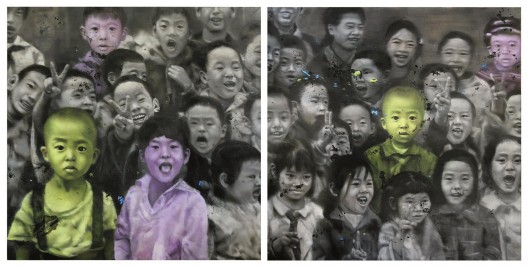

Complaints, there are a couple, all be they trifling. Specifically, the image used in the poster widely deployed to promote the show was from Li Tianbing’s “Ensemble No. 1+2” (2008). It is a workman-like painting of children smiling. Of all the works the museum could have chosen, this was one of the least interesting and almost kitsch in its portrayal of cute Chinese children being cute. It panders to certain uninformed Western preconceptions about recent Chinese art. The misrepresentation does the collection a disservice, even if it was an easy invitation for a perhaps underestimated public. More generally, the scope of the exhibition is also its limitation. There is not time enough to properly consider the outsized influence of numerous artists such as Zheng Guogu, even though numerous paintings of his were displayed. And some works perhaps should have been included (not least those of Zhou Tiehai). But there will be time for that later.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, the vast Herzog & de Meuron–designed M+ museum is rising, a part of the ambitious West Kowloon Cultural District redevelopment (H & de M are also Swiss—with Ai Weiwei they designed the “Bird’s Nest” stadium for the Beijing Olympics; Sigg was an advisor). Since the dramatic announcement in June 2012 that 1,463 works from the Sigg Collection would be donated to the nascent institution, it was clear that one of the museum’s first exhibitions would be devoted to it. As a prologue to its slightly delayed opening in 2019, in April this year M+ put on exhibition part of the collection. The curator was M+’s Sigg Senior Curator, Pi Li, one of the most influential international curators from China, with a biography that includes magazine editor, noted gallerist and Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) professor.

Pi Li managed to squeeze some 80 works by 50 artists into a relatively small space at ArtisTree, a somewhat anonymous visual and performing arts center at Taikoo Place (both of which are owned by Hong Kong multinational Swire Properties). Yet only occasionally did it feel over crowded, despite a throng of both excited and contemplative visitors (all happily taking photographs). Divided into three thematic-chronological parts (1975–1989, 1990–1999 and 2000–2012), the exhibition was a primer and a map. The first part concentrated on the Stars Group, linking it to its predecessors and foregrounding post-1989’s Cynical Realism. Notably, this chapter included hitherto unseen film by Chi Xiaoning of the Stars’ brief exhibition hung on the fence surrounding the National Art Museum in 1979, and including Liu Heung Shing’s photograph of CAFA students painting a nude model (CAFA had been closed during most of the Cultural Revolution). The importance of institutions such as the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou in providing crucibles for talent to develop (however unintentionally) is still greatly underestimated in the West. Particularly arresting works in this section include Huang Yong Ping’s Duchampian “Six Small Turntables” (1988) and Geng Jianyi’s (b.1962) “The Second Situation” (1987), whose gurning heads predate those of many comrades (as Phil Tinari notes in his Artforum review of the show, this work was completed for the influential 1989 “China/Avant-Garde” show at NAMOC, the National Art Museum of China).

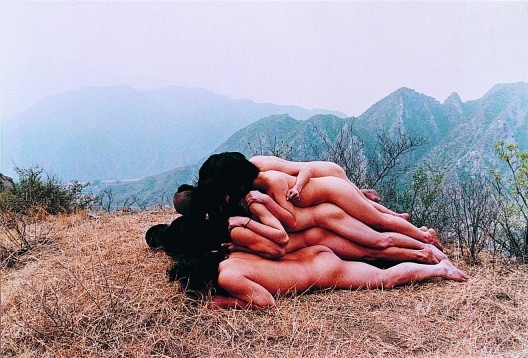

The post-’89 chapter witnesses an inevitable shift in sensibility. The 1990s signaled the rise of Cynical Realism as an overly effective antidote to conceptualism, and the early 2000s saw it lose its original moorings. Here we see a bevy of superstars huddled together, including Liu Xiaodong, Wang Guangyi, Fang Lijun, Yue Minjun, Zhang Xiaogang, and Zeng Fanzhi. But circumstances also caused a rebirth in which experimental video and performance were embraced, along with Dadaist humor. Zhang Peili’s video “Water (Standard Version from the Cihai Dictionary)” (1991), presents renowned news reader Xing Zhibin blandly reciting definitions of basic words as if they were the nightly news. Other key works include Xu Zhen’s reddening back being slapped by an invisible hand (“Rainbow”, 1998), a face-down Song Dong puffing the condensation of his breath into ice (“Breathing, Tiananmen Square”, 1996) and Lin Yilin’s obstructionist “Safely Maneuvering Across Lin He Road” (1995).

The final chapter is a question—where now? Perhaps strong themes are present already but as yet they are unclear, or we are yet blind to them. Are Chinese artists, like artists everywhere, becoming just artists? These questions are not random. Yang Fudong has similar thoughts in his “Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forrest” (2003–2007). Liang Yuanwei quotes Stanley Kubrick’s writers-block reveal in The Shining with a typewriter and accompanying toilet roll covered with the nota bene “Umustbestrong” (2004–2005).

The M+ exhibition existed in earlier formats. The colophon on page 150 of the M+ catalogue notes that “Earlier versions in Swedish and English of this publication, titled Right is Wrong was [sic] co-produced between Bildmuseet, Umeå University, Sweden and M+, Kowloon Cultural District, Hong Kong, in 2014”. As Phil Tinari noted in his review:

Wang [Xingwei] was represented by the painting [“New Beijing”] that graced the catalogue cover of previous iterations of the exhibition in Umeå, Sweden, and Manchester, UK, and whose appearance there triggered the heightened level of scrutiny from Hong Kong authorities that eventually led M+ to abandon not only this cover image but the show’s original title, “Right Is Wrong.”

The image is based on a famous photograph by Liu Heung Shing of injured, perhaps dead, protesters being rushed through the streets by their comrades on one morning in June 1989. In Wang’s version the bloody activists are replaced with plump penguins—not pandas, but an odd sort of flightless bird that is out of its element. Liu’s photograph appeared in the first part of the exhibition and, as Tinari notes, the photograph shares “a refracted sight line with the painting, uniting tragedy and farce.” Of course, propagandists have long been dab hands at photo-collage, helping to clean history of inconvenient and messy presences—just ghosts, really.

At the time of Sigg’s donation, the collection’s estimated value was some USD 163 million. In addition, a further 22 key works were sold to M+ at a generous discount. But the real value to M+ and more generally to the people of China is incalculable. No other donation to any museum in recent decades is as important as this one. For a long time, Sigg intended to give his collection to the Chinese people and would have given it to a Mainland institution, but he wanted to be sure that such a museum would not only take care of the collection, but also exhibit it to the people to whom it would belong. Thus, M+ is something of a compromise. Hong Kong is China, but also not: Deng Xiaoping’s governing principal of “one country, two systems” means that most Chinese people cannot (easily) visit a part of their one country, nor can they (easily) visit the greatest collection of their own art from the past 30 years. A museum like M+ is indubitably a form of soft diplomacy, but it is also a treasure box conveniently and carefully cocooned from 99.5% of China’s population. Those Chinese visitors who had the good fortune to travel to Bern were able to visit an exhibition twice as large as the one in Hong Kong. But not better.

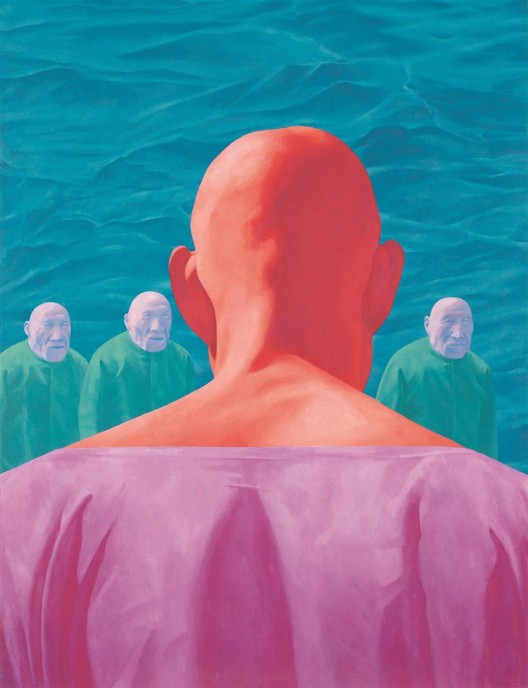

Fang Lijun, “Untitled”, oil on canvas 250 x 180 cm, 1995. M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong (by donation) Courtesy of the artist and West Kowloon Cultural District Authority.

Liu Ding, “Products”, 40 tableaus, furniture, carpet, dimensions variable, 2005 © the artist. M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong. By donation.

Zhang Peili, “X? Series No.4″, oil on canvas 180 x 198 cm, 1987. M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong. Courtesy of the artist and West Kowloon Cultural District Authority.