“Fairy Dreams in Peach-Blossom-Valley,” Liu Chuanhong Solo Exhibition

A Thousand Plateaus Art Space (No. 87 Fangqin Street, Gaoxin District, Chengdu) Dec 24, 2012 – Feb 23, 2013

The ancient poet Tao Yuanming describes Peach Blossom Spring as a small village one stumbles upon by chance. It is a pristine paradise hidden deep in the wilderness of mountains, where its inhabitants are protected from the outside world; the old and young alike live in harmony with the birds and beasts. Undoubtedly, it would be the perfect sanctuary for a recluse, and there have been no shortage of hermits in the Chinese literary tradition. Writers and poets in ancient China had their many motivations for seeking solitude. Some cloistered themselves because they felt neglected by those in power, others fell out of political favor, and still others could not live with the vagaries of life and simply turned away from society. Many among them were talented in all the traditional arts (the qin zither, go/weiqi, calligraphy, painting, poetry, literature). Hidden away in the mists of the mountains, they could hone their crafts even more. But in the utopia of Peach Blossom Spring, one makes art for oneself, not for an audience. In the contemporary society of modern China, one still hears rumors of this or that artist vacating to the countryside, purchasing some land, and finding fulfillment by working in the fields. By retiring from the city, they seek to nurture their creativity by moving with the slower rhythms of a life far from the crowd.

However, the reality of rural life in contemporary China exists on the margins of urbanization and modernization. The majority of working youth abandons the village and heads to the cities to eke out a life, leaving behind the very young and the very old. The tradition of passing down land and homes from one generation to the next has gradually been replaced by standardized rehousing policies. Memory is obscured by the dust of cranes and cement mixers. The blood-red flow of history has become so diluted by the swift torrent of time that it is nearly transparent. The landscape of China’s future is unprecedentedly foggy, but there is no one left to paint us a picture.

Liu Chuanhong’s oil paintings have the ink-filled poetry of traditional Chinese landscapes, but they are done through a combination of pointillism and layering. In his paintings, moonlight shines through the haze, and clouds continuously move through the high mountains. Since 2002, he has lived in Lin County, located in Henan Province, and his time spent in his village (the anglicized name of which happens to be Peach Blossom Hollow) has imbued the series Mountain Forest Picture Book with soul. His ambiguous hills of dawn or dusk are limned with traces of mist; trees and stones alike evoke a sense of melancholy. It is unclear if his fallen leaves are covered by frozen water or rolling mist, while above, the bare and fragile limbs of the trees stretch toward them as if in longing. Liu’s paintings depict mountain ranges that could be valleys, and he draws delicately supple peach blossoms that evoke a boundless chill. The bamboo forests seem to sway to the sound of the wind, while the white of fallen snow does not bleach the wilderness of the forest but instead adds an element of vitality. The many paths in his painting are at times occupied, at times not, and they are covered with footprints that appear and disappear.

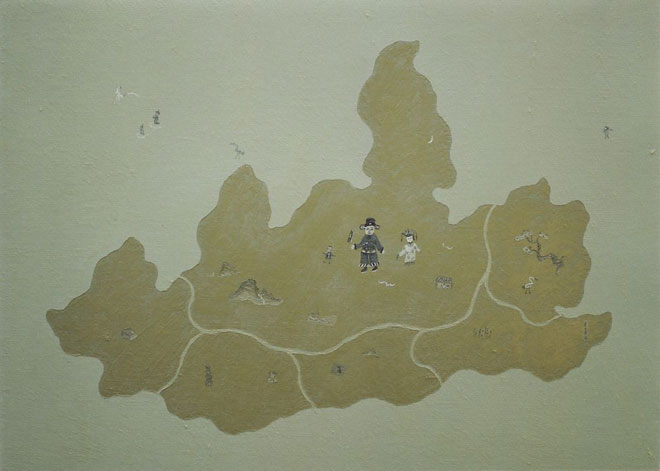

Liu dons a bamboo hat and enters his paintings; cloth bag in hand, dressed in plain homespun garb, he transforms into his childhood heroes — Lin Chong of The Water Margin or fictionalized Shanghai gangster Xu Wenqiang. Diary in hand, he sets out for adventure. The storylines of The Water Margin and Shanghai Bund (Shanghai Tan) are inexorably linked to Liu’s narrative, as it wends its way through the hazy scenery of his paintings. His drawings and hand-written notes, along with his personalized maps, are part of a unified whole. The artist meticulously lays out rivers and mountain ranges, notating place names which may or may not exist. He maps out the geography, delineating the veins and grid of his creativity, pinpointing his position in this world.

刘传宏 Liu Chuanhong, “西游记——知识分子2 Journey to the West—Intellectual 2,” 布面油画 oil on canvas, 50×65 cm, 2002

刘传宏 Liu Chuanhong, “林冲入豫北记——第十三场 太平林场 Lin Chong Enters Northern Henan—Scene 13: Taiping Forest,” 布面油画 oil on canvas, 70×128 cm, 2012

On the other side of the grid is Liu’s emphasis on history and memory. Using his maps as a starting point, he has forged all sorts of alternate realities. Referencing the real Red Flag Canal at the foot of the mountain where his village is situated, he created the series, The Moonlit Red Flag Canal (2006-2010). The series takes its name from the third part which is preceded by the “autobiography” of a “Liu the Third,” entitled “My Life,” and “Hongxing Warehouse.” All three parts are hand-drawn on sketch paper dating from 1978, and on old rice paper and watercolor paper. In the first part, Liu Chuanhong tells the story of “Liu the Third” with sincerity that does not eliminate flair. “Hongxing Warehouse” and “The Moonlit Red Flag Canal” describe the history of the town starting with the inception of the Republic of China and ending with the reform and opening-up of the nation. The three parallel narratives extract and expand on key events taking place over the course of a few tumultuous decades. It focuses the audience’s attention on the three dimensions of person, organization, and community. All of the documents in this series are obviously fraudulent, because the artist does not care if his audience will take him at his word or see through his manufactured history. It is the whole of the story told through these images and texts that Liu finds significant. Through the entirety of his work, he urges his audience to recognize and reflect upon the past. Liu abstracts time into a false construct, with his chronological arrangement of so-called facts, reflecting the untruths existing in contemporary life. History rapidly insinuates itself into the present, the present only lasts an instant, and the future continuously recedes into the past.

刘传宏 Liu Chuanhong, “林冲入豫北记——第八场 水段村路上 Lin Chong Enters Northern Henan—Scene 8: on the Way to Shuiduan Village,” 布面油画 oil on canvas, 67×100 cm, 2012

With the current eagerness of contemporary Chinese artists to imitate the paintings of ancient masters, and the tendency of some of these artists to exaggerate their tradition and literature infused personae, the feeling of being one with nature is often absent. That is why Liu Chuanhong’s authentically illustrated narrative is a rare gem indeed. His ability to inject necessary humor into the mix of historical material, politics, and economics makes his work all the more unusual. As early as 2001, Liu inserted himself into his first series of oil paintings entitled Journey to the West as Buddhist monk, Xuanzang, journeying into the wilderness in search of solitude. Over a decade later, Liu Chuanhong has found his Peach Blossom Spring, and become the solitary wanderer of his dreams.