Ran Dian Ink

This article was originally published by PIFO Gallery

Empty-handed, I carry a hoe.

Walking on foot, I ride a water buffalo.

As I pass over a bridge,

The bridge flows but the water does not.

As part of his recent series of paintings, Wang Chuan transcribed this poem encapsulating key tenets of Buddhism (2013 No. 71). As the artist’s chosen text, we can expect it to offer insights into the paintings he created around the same time: it may be a key to understanding the series. The poem’s first two lines convey the concept of passing through the world without becoming attached to things—making use of them when appropriate and then letting go. The second half of the poem concerns the belief that the world, like water, is in a constant state—albeit one of flux. Our relationship to the world, not the world itself, is the thing that is undergoing change.

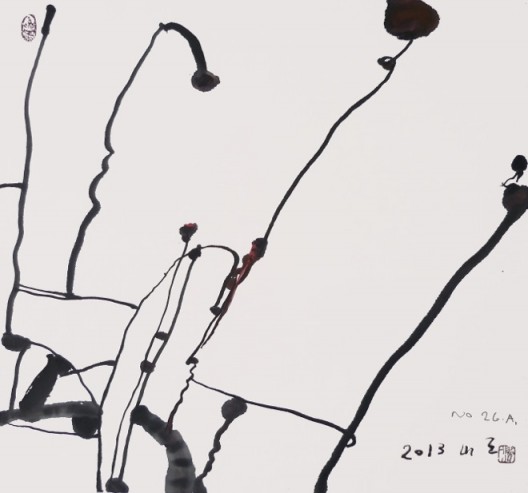

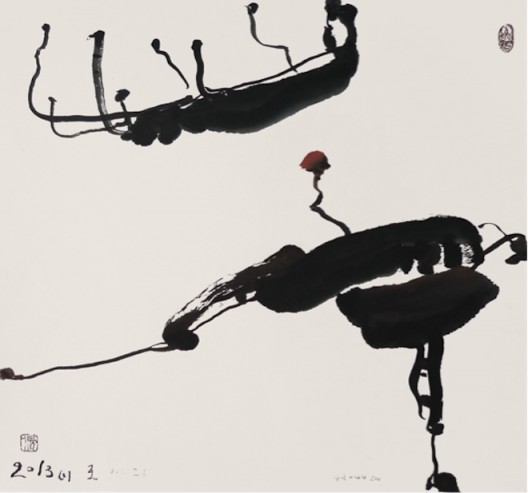

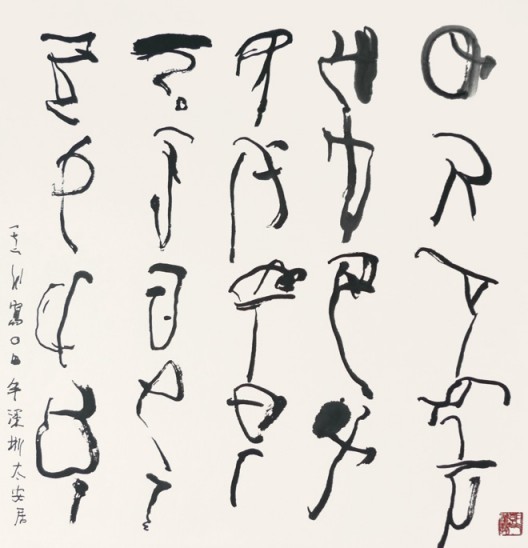

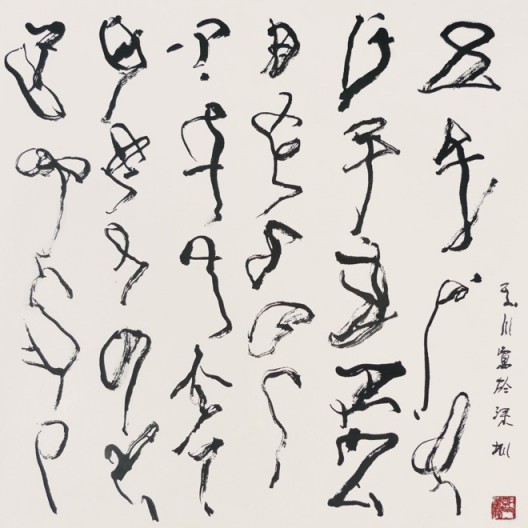

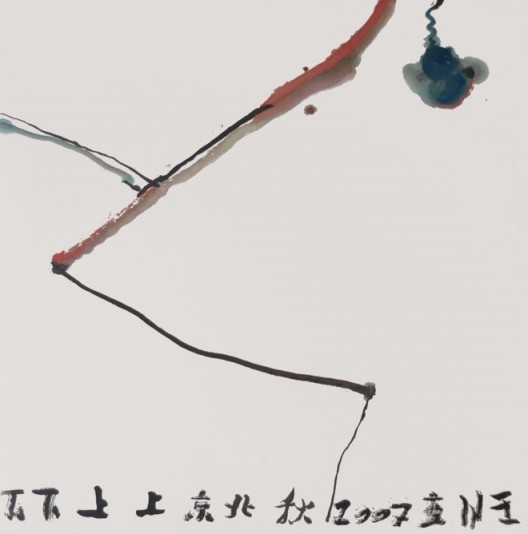

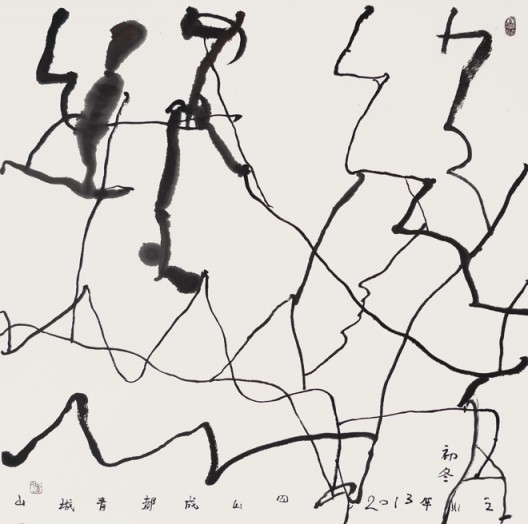

Wang Chuan’s ink paintings of the last several years hum with a quiet energy. That energy tends to be spread evenly throughout each work, with stronger eddies here and there, sometimes punctuated by dots or color, but rarely a major concentrated vortex—just as the energy in an endlessly flowing river. There are nodes of energy where lines thicken, and the lines intersect in a web that stretches to infinity. Recognizable shapes on the verge of emerging into plain view dissolve before solidifying: in an act of non-attachment, the artist releases the form rather than holding it close. At times the works do suggest particular subjects, dramatically abstracted, but the paintings remain so far from representational that possible subjects slip away from certain identification. 2010 No. 54 resembles a bridge with water flowing underneath (as in Master Fu’s poem); 2007 No. 53 might be a leaf or skiff adrift upon a stream (see the final two paragraphs here); 2013 No. 82 looks like tiny flowers or mushrooms on long slender stalks; and 2013 No. 77 might depict many-legged creatures. Or they might just as well be entirely non-representational. Even the text is not readily interpretable: that of 2004 No. 48 suggests letters of the Roman alphabet, but it is Tibetan, as is the rather different writing on 2004 No. 49. Does the inscription shang shang xia xia 上上下下 (“above above below below”) on 2007 No. 56 simply describe the existence of two lines above and two below?

By the end of his life the author of the poem, Master Fu 傅大士 (b. 497; also known as Shanhui 善慧), had acquired many followers, including Emperor Wu of Liang. He did not follow the common path to Buddhist enlightenment, however. He began life as a farmer, and instead of relying on a teacher to show him the way, he became enlightened through his own actions and experiences. Wang Chuan achieved a new understanding of the meaning of life, or how one should live in the world, through a profound experience that was not at all of his choice: like Master Fu, the world did not change, but his relationship to it did. The crucial event for Wang Chuan was his 1998 diagnosis with gastric cancer, an extremely serious form of cancer if not caught early. The immanence of death and the certitude of mortality, as confirmed by diagnosis of a fatal illness, not surprisingly can catalyze a new valuation of life, and such was the case with Wang Chuan. He decided to travel to the Buddhist center of Dharamsala in Nepal, and his sojourn there from August 2002 became an important turning point in his life. He found peace. Even more remarkably, towards the end of that year, following a profound and dreamlike episode of spiritual acceptance, he learned that his supposedly incurable cancer was completely gone.

The peace Wang Chuan found within himself infuses his paintings. They don’t overwhelm the viewer, nor do they convey a pithy or amusing message. They don’t charm or seduce, or grab the viewer’s attention. Instead they stand as a reflection of the constant flow of energy through the world around us, as channeled through Wang Chuan. Contemplating one of his paintings we can sense this, and sense that the painting is exactly right, exactly as it should be with nothing to add or subtract. To paint thus is ever a most challenging feat for an artist, particularly when the artist eschews all visual distractions in his art, as mentioned above—no message, no overwhelming power, no recognizable image, and so on.

The act of painting with ink on paper is part of the flow of Wang Chuan’s life. He sleeps only four or five hours per day, but devotes an extended period to meditation. When he brushes ink across xuan paper, it is an action of his quiet mind, and a mark signifying the passage of time in his life, a life extending beyond what had once been the expected limit. Just as not every episode of meditation is profound and deep from beginning to end, so too is not every episode of painting. Wang Chuan consigns many paintings to the waste pile because they are in some way lacking—not fully expressive of his best self.

Ink painting with brush on paper is an intimate expression of the self, as the hand wielding the brush acts in accordance with the mind. There is no going back: no changes can be made, no faults erased. The great Chinese ink painters had mastered the brush, but the painter’s mental state was at least as important as superb technique. China’s Chan Buddhist painters deployed ink with seeming abandon yet achieved incomparable results, ascribable to their elevated and totally free states of mind. When Wang Chuan’s paintings are at their best, it is because of his peaceful and open mind, his equanimity regarding life. His lines exist for the joy of the process: they don’t necessarily have an obvious external goal such as to describe a structure, or balance another line, or close off a particular form. They may seem to meander but they exist simply as part of life. In a work like 2013 No. 68 the lines feel like music stretching across the void. Wang Chuan inscribed 2013 No. 69 with the name of a mountain but it is not clear whether that is both the subject and the location of the artist when he painted it, but the lines have the same feel as those in 2013 No. 68, as strands of energy traversing the universe. They are not overtly strong, but there is an inner strength that carries them along wherever it is they are going. Wang Chuan seems to paint for the sake of the painting process, not for the end goal of a finished work of art. In art as in life, to be in the moment, fully participating in the process rather than gazing ahead toward a goal, is the way to fulfillment.

In a short statement titled “An Old Leaf in Front of My Eye” (眼下的一片老叶子 Yanxia de Yi Pian Lao Yezi, 2006),[i] Wang Chuan describes the profound spiritual experience he underwent in October 2002. Having wandered for hours lost in the dense and humid forests of Pohkara, exhausted and covered in leeches, he finally sat down and surrendered to the situation. The sight of an old leaf fallen slowly through his field of vision, “like a boat directed only by the current and wind, its destination beyond understanding,” moved him deeply. It is then that he gave up the futile struggle against fate and achieved equanimity. He believes that at this moment his cancer was eradicated.

Wang Chuan closes his statement with the rumination, “Painting is an illusion of the eyes or of the mind. . . . Words do not represent any thing. . . . Sentences are only an introduction to the eternal truth. ” We can view his abstract ink paintings as introductory spaces for personal spiritual pondering.

[i] Wang Chuan 王川, Wang Chuan Youcai Zuopin 王川油彩作品 (Wang Chuan’s Oil Paintings) (Shanghai: Zhu Qizhan Art Museum, 2006).