Despite the appearance of new museum landmarks in China promising a new cultural epoch, it has been art works that have left soft marks of something more lasting in 2014′s landscape of pristine concrete, granite and glass.

Xiao Yu’s “Ground” brought a cow into the immaculate space of a Beijing gallery to plough an expansive area of earth clenched within a low concrete wall. This was not the ground of Walter De Maria’s “The New York Earth Room” (1977), an obvious reference point tinged with magic potential, nor the zone of fecundity of Agnes Denes’ “Wheatfield—A Confrontation” (1982). In the sunless light of Pace’s clean Beijing gallery I found this to be hopeless, arid soil—the concrete-blasted residue of new construction sites. The artist’s efforts to plough it broke it up into large, infertile shapes, disrupting a defined area for prime real estate. Traditional agricultural labour was rendered purposeless, reduced to a poetic and rhetorical act as out of sync with the contemporary city as the contemplation of mountains and lakes.

Xiao Yu, “Ground”

萧昱,《地》

Xiao Yu, “Ground”

萧昱,《地》

Cai Guo-Qiang’s show at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai was a hit, and deservedly so; many works were created spontaneously and on-site for live audiences, tackling ecological themes head on. I found “Silent Ink”, the massive black lake torn into the fabric of the building and relentlessly seeping into its industrial history, a transformative force from the past. The staged presentation, the pungent smell and the meeting of elements suggested beauty, poison, contamination and purity. The scenario was immaculately realized with devastated reinforced concrete that had once been the floor artfully lit and arranged. Gentle ripples on the surface reflected the bodies of urbane visitors.

Cai Guo-Qiang, “Silent Ink”

蔡国强,《静墨》

Li Ming’s fast-paced eight-channel video, “Movements”, at Shanghai’s Antenna Space managed to be sardonic as well as hilarious. The movement of the title across a scroll-like space followed the arrival of the migrant in the city. In his urgent journey he hitches lifts, progressing through from independent to collective forms of transport, only to find himself dropped off at a peripheral construction site. He looks around. At the end of his dash through the screens from right to left, he finds his progress was always aimless.

Li Ming, “Movements”

李明,《运动》

Jeffrey Shaw’s immersive “Advanced Visualization and Interaction Environment (AVIE)” at Shanghai Chronus Art Centre produced a radically different surface—all-encompassing and in 3D. The environment played host to a changing program of interactions and experiences. Besides the complexity of the spaces and narratives, the works provided a context to discuss new media research. Chronus were generous to have hosted a seemingly endless succession of visitors introducing new voices that questioned the scope, place and potential of new media.

Jeffrey Shaw, “Advanced Visualization and Interaction Environment (AVIE)”

邵志飞,《先锋视觉和交互环境(AVIE系统)》

New media’s relationship with gaming was scrutinized across a number of shows, such as UCCA’s “Art Post Internet” in Beijing, Barbican’s “Digital Revolution” in London, and Shanghai K11′s “Metamorphosis of the Virtual World 5+5”. At the latter show, Feng Mengbo’s “Vector Drum” dragged the seductive history up from its roots, depicting a primal creative act enveloped in the hiss of a green cathode tube. The artist pulls back, providing an uncommon view beyond the screen itself. The human interface is the foreground in the form of a hand protected by a glove—a techno-homage to Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam.”

Feng Mengbo, “Vector Drum

冯梦波,《矢量军鼓》

Li Qing’s “Mementos—Asian Scenery”, a heap of hand-crafted and painted vintage gaming machines, did a similar job with no technology at all. If some of today’s artists are engaged in understanding the historical intermingling of real and virtual lives, these fairground-like boxes are simultaneously stage, training ground and a reservoir for preserved memory. Their presentation as a minimalist stack of expended material draws attention to multiple pasts remembered in multiple real and virtual places, rather than to unity—the future mediated by a single digital technology.

Li Qing, “Mementos—Asian Scenery”

李青,《纪念物•亚洲风景》

Elsewhere, it was facilitated production rather than curatorial effort that amplified artist’s ambitions and turned their speculations and proposals into magical objects. Just such an effect created the impressive, “Solo Show by Robbie Williams” at the Shanghai Biennale, an ensemble of works without an author evoking the traditional image of a galloping horse. In a similar gesture, Xu Zhen’s tiny stuttering utterances were realized as oxidized iron plates by MadeIn Company. Through this relationship his humane first sound, Da…Da…Da…Da was transformed into the permanent formality of Richard Serra like sheet metal.

MadeIn Company, “Da…Da…Da…Da”

没顶公司,《嗒…嗒…嗒…嗒》

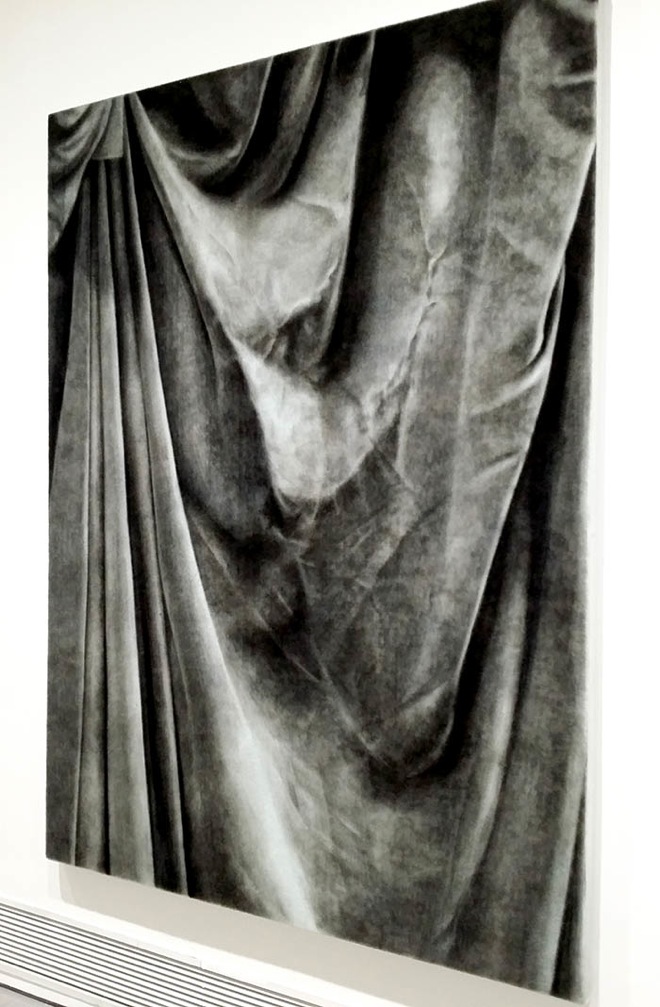

Zhang Yunyao’s engrained works in graphite on felt created a marriage of industrial residue with the suggestion of a classical image. At the John Moores’ Prize exhibition at the Himalayas Museum, the work “A Piece of Flannelette (classic)” provided weightless relief against the earnest subjects and worked surfaces that got the prizes.

Zhan Yunyao, “A Piece of Flannelette (classic)”

张云垚,《一块绒布(古典主义)》

Through a handful of large-scale works deployed in front of the Himalayas Centre, for me it was Hu Xiangcheng who most succinctly expressed a yearning for the values and textures of old cultures, suggesting something malleable—a negotiated public art without public space. These works addressed the controlled forms and even planes of China’s developing economy. In one work, what at first glance appears to be a steam roller is found to be a life-size simulacrum, carefully remade in recycled wood. The wood often retained carved decorative idiosyncrasies. This substantial illusion stands on a circular concrete track. Where a real roller would have smoothed out this surface, eradicating the imperfections of human manufacture, this hand crafted machine has pressed a memory into the surface. Its circuit has left a now solid trail of subtle imprints. Following a short journey, imprinting the track, it returns to stand at its point of departure.

In 2014, it was nice to be reminded that when it comes to new cultural monuments, we need history to make the present. Scale is relative to the individual, but impetus needs a collective.

Hu Xiangcheng‘s public art

胡项城的公共艺术