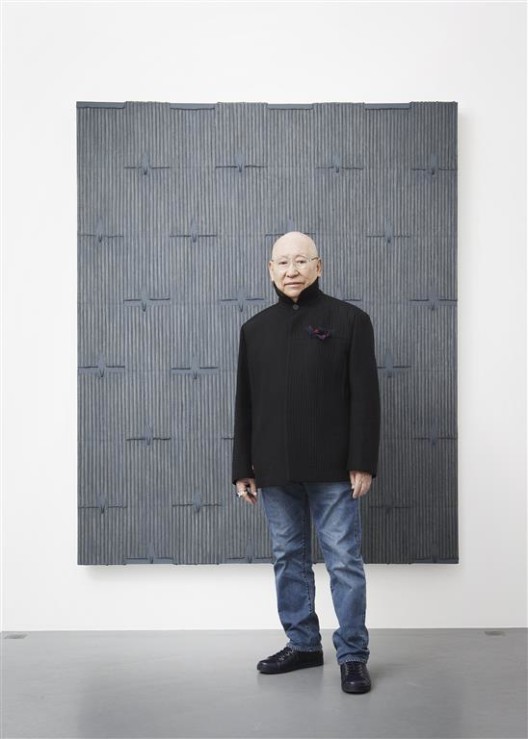

Park Seo-Bo (b. 1931, South Korea) is recognized as one of the fathers of Korean modernism. Disenchanted with the realism prevalent in Korea in the 1950s, with his world shaken by the outbreak of civil war, Park turned towards abstraction and was a founding member of what came to be known as the Dansaekhwa monochrome movement in the 1970s in South Korea. In conversation at the opening of a new solo exhibition “Ecriture” (the name given to his monochrome works which has since become the generic title of all his artworks and exhibitions since 1967) at Galerie Perrotin New York, Park recalls the early beginnings of his work, and the circumstances and compulsions that have generated it. He spoke passionately of the hard-won path into his artistic practice and, in hindsight, with great confidence.

Park Seo-Bo was a young man when the Korean War broke out in 1950. Many of his friends died from gunshot wounds and lost limbs because of the war. Park befriended American soldiers stationed in Korea who shared their food with him. For want of art materials, he used lunch boxes as canvas and sold his watch to buy oil paint, making a self-portrait—his first. His teacher told him never to lose that painting. But it was stolen.

Visiting the national art museum in 1956, Park repudiated the paintings hanging there, saying they all looked the same. Such realist works were supported by the government; his declaration lost Park his job. He felt great anger at the war, having lost dear friends and his work. In its aftermath, Park realized that his work should not depict how he looked realistically; rather, he aimed to destroy himself—and to depict that. This fundamental self-destruction, he says, led him towards another kind of artistic creation: “It was such a dramatic moment in my life”.

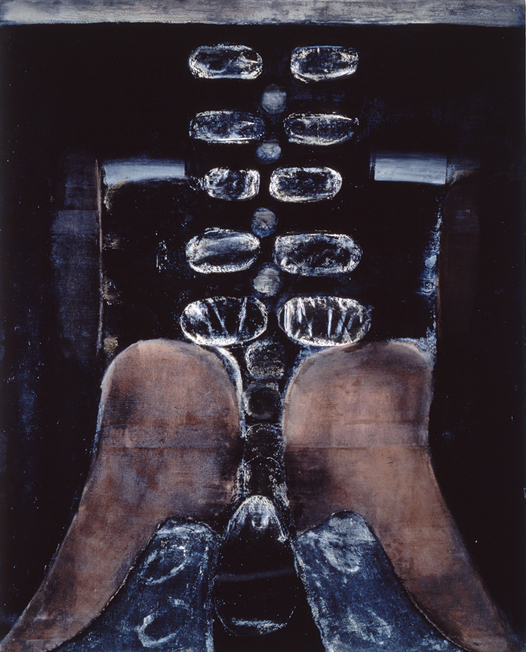

For the 1963 Paris Biennale, Park submitted “Primordials”, an artwork he had made in 1962: he had cut a space in the canvas and put another canvas underneath. When the accepted piece appeared in the newspaper, a reporter described it as “Black Breath”. At the time, Park says, there was no satisfaction in his life. Expressing his post-war anger made the work strong, he felt—stronger than American Action painting.

After 1960, Park slowly forgot his war experiences; as time passed, the war became more like a story, while the art movement also changed so that artists popular in 1960 were far less famous by 1965. In 1961, Park had the chance to apply for a UNESCO art contest. He visited Paris in 1961 to participate—but once there realized there was no such contest.

He resolved to stay in Paris to find out what was going on, which extended to a year of work and study. Park supported himself by working “from morn till night”, for example as an assistant at a gallery. It was a harsh time, he recalls, and he relied heavily on friends who helped him. A lack of funds, however, was no bar to Park’s artistic ambitions.

“Because I had no money, I used rubbish to make artworks. I had a friend who was an art critic, and he had a German girlfriend; I used her old stockings, putting them on the canvas and burning them—it looked like burnt skin.”

Poverty is the mother of creation, Park believes; while in Paris, and despite limited means, he drew attention and support from sponsors. Speaking recently at the opening of his solo exhibition at Galerie Perrotin in New York, Park said he feels angry when he sees painting that demonstrates only the artist’s technique, as art should incorporate both technique and the spirit of the artist. He observes that most artists in Europe or America are very conceptual in their art work; he dislikes this. Pointing at a piece by Bernard Frize (“Miscela”), Park remarked that such work has also been done by a Japanese artist, with the same concept—he dislikes this derivative tendency .

Working as a professor at a Korean art school, Park shook up the system, introducing new teaching techniques—for example affixing materials and objects to the wall or floor for students to observe and work from.

Park recalls a professor of Matisse whom he admired who told his students not to follow anything but to create their own paths. It was an approach Park strove to emulate in his classes, giving his charges three rules which he wrote on the wall:

1. Do not follow me

2. Do not be influenced by history

3. Do not follow each other

With his unique curriculum, however, a group of professors started to oppose him and sought to have him removed from the school. He left in 1966, the point at which Park embraced his own work as a full-time artist. In so doing, he realized the influence of Western culture on his own work. “I don’t have a high nose, I don’t have blue eyes. Why am I influenced by Western culture? I should get rid of this.” Seeking his real self, Park stopped working for one or two years just to read, a process which led him to realize that “finding what I am means getting rid of what I am.”

“In trying to empty myself, I found the answer—I needed to empty myself but didn’t know how to. I looked books for an answer in books, but couldn’t find it.”

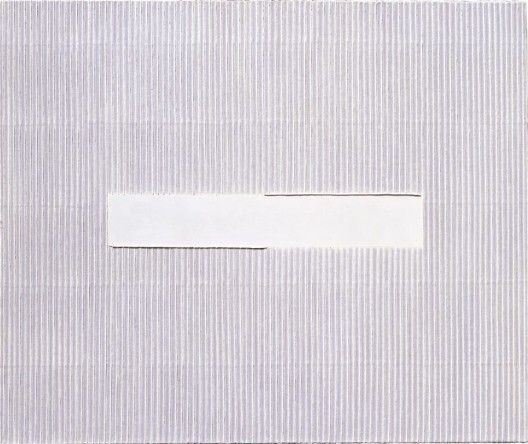

The breakthrough came with his own sons, along with the understanding that answers could be found anywhere. Park describes a moment when his second son was two or three years old, playing with his older brother’s notebook. Too young to fit a single Korean character into each square as intended for writing practice, the little boy’s attempts were all over the place. Frustrated, his older brother scribbled all over the page with an eraser. This was to be the starting-point for the work for which Park is now so well known.

In his own words: “It was that giving up which was the point.”

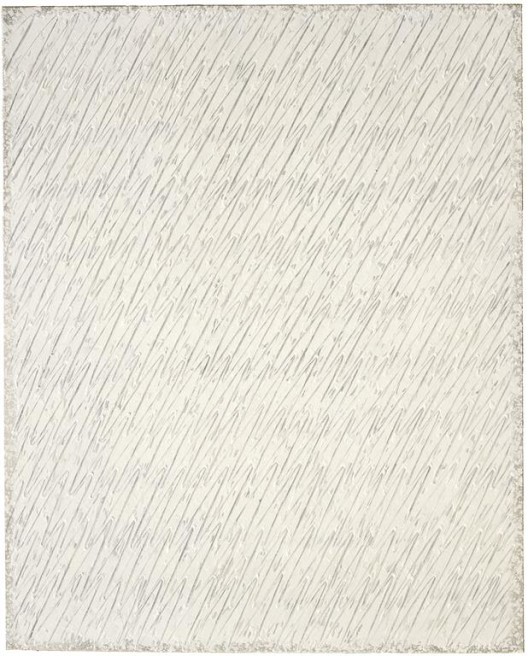

Park Seo-Bo, “Ecriture No. 90-85″, pencil and oil on cotton, 162 cm x 130 cm, 1985. Courtesy Galerie Perrotin.

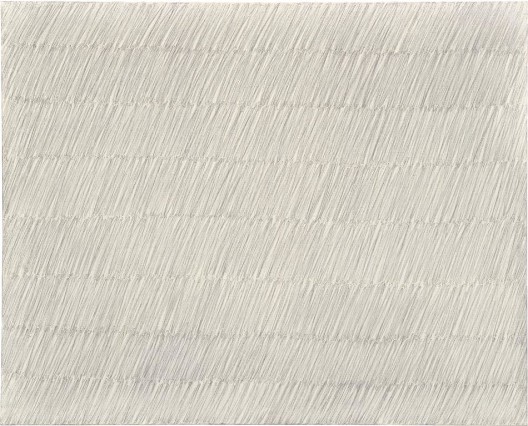

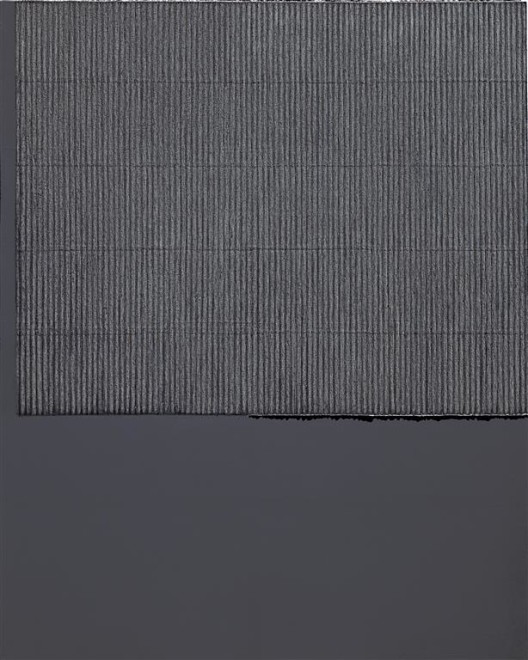

Park Seo-Bo, “Ecriture No. 980308″, black ink, white clam and oyster shell powder and glue with Korean Hanji paper on canvas, 228 x 182 cm, 1998. Courtesy Galerie Perrotin.