Simon Lee Gallery, New York

The advent of the home studio in the 1970’s democratized both music and art, with cities like New York becoming significant platforms for the convergence of both practices. Partially due to financial instability brought on by urban decay and political neglect, artists embraced a do-it-yourself mentality which inevitably led to interdisciplinary experimentation. Although this time period was marked by metropolitan downturn, the phenomenal successes of these new wave forms of art making led to their ironic commercialization. Through a diverse group of artists and media, New Pleasure showcases the intersection of music and art after punk rock and investigates how artists have taken direct influence from musicians, have participated within either genre, or have performed as musicians themselves.

A number of the artists presented in this exhibition have also practiced as musicians, including Condo, Chopin, Dalwood, Gordon, Roberts and Vega. Dalwood, who performed with influential Bristol-based punk band The Cortinas left the group in 1978 to pursue a career as an artist. Focusing on the legacy of some of history’s most significant individuals, Dalwood’s paintings are the composite of factual evidence and our collective imagination. In New Pleasure he presents Second Set (2016), a painting capturing two different moments in time within one image, whose composition echoes the aesthetics of Lou Reed’s album cover for Transformer. Another musician turned artist is George Condo, who toured with a punk band in the late 70s. This led to chance introductions to artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring; the latter allowed the young artist the use of his studio in 1985. As Condo would recall, it was there he completed a painting dedicated to Miles Davis, one of many musically informed works that followed. Included in this exhibition is John Lennon (2001), an energetic yellow abstract painting cut abruptly at its head with a stark blue background with blocky red letters reading the titular musician’s name. In this group of works he makes connections between his own improvisations and those of the musicians and writers that inspired him. They exist as a literal reassessment of his debt to music as the touchstone for an understanding of free expression in the visual field.

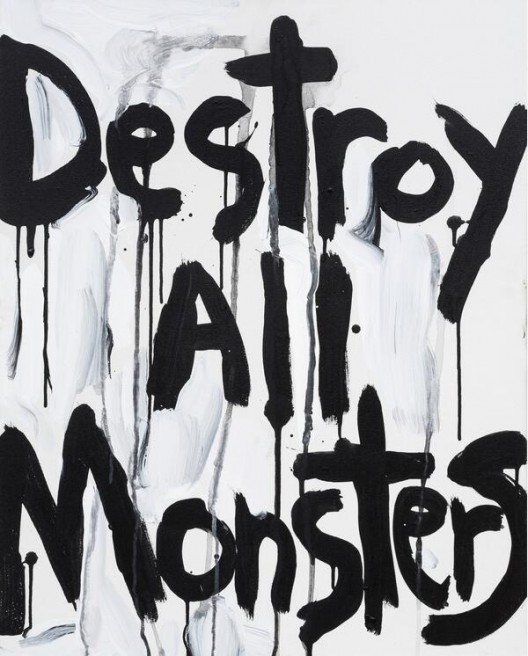

Other artists, such as Gordon, Vega, Roberts and Chopin are primarily known for their contributions to music rather than art yet each have an extensive body of artwork. Vega, the vocalist for the influential band Suicide, studied under Ad Reinhardt in the 60’s where he first made assemblage sculptures from found objects. Within the gallery he presents a makeshift crucifix, a common trope for Vega, adorned with three light bulbs of different designs. Gordon, like Vega, also came to prominence within the downtown music scene. A founding member of Sonic Youth, Gordon has since made socially-conscious paintings from layers of paint and glitter. Often addressing issues of gentrification, protest, and resistance with her practice, her work in the exhibition entitled Destroy All Monsters (2015) makes reference to the band name that artists Mike Kelley and Jim Shaw performed under. Roberts and Chopin both have interdisciplinary practices that mix experimental music with art. Like her music, Roberts’s work deals with the composition of history and memory. On view here is Always Say your Name (2014), a triptych collage of handwritten sheet music and found photographs interwoven with layers of charcoal and paint. One of the most accomplished avant-garde musicians of the 20th century, Chopin was a practitioner of sound poetry. Within the gallery are two examples of the deceased artist/poet’s typewriter poems that reference both music and dance.

The impact that listening to music can have on an artist’s practice is exceptional. This exchange, however, is just the surface of the ongoing discourse between music and art. Compositions both illustrative and conceptual manifest themselves through this tête-à-tête. Parmiggiani, Feldmann, Parrino and Wool all find inspiration for their work within music. Most literal are Feldmann’s photographs portraying different models of car stereos, each taken by the artist while “good music was playing”. While Feldmann presents the vessel for music, other artists show how this art form can manifest itself visually. Visceral and expressive responses to music by Parmiggiani, Parrino and Wool are presented within the gallery, each piece showcasing moments of quick action. Like a power chord or record break, these pieces are documentations of a broken space in time.

Works by Carpenter, Echakhch, Lloyd and Prince deconstruct the phenomenon that music’s influence has on our collective consciousness. Echakhch presents Sans Titre (joueur de tambour a) (2010), a sculptural work consisting of abandoned civilian clothes scattered around a marching-band drum. Here, the musical object is divorced from its traditional function and silenced further by presenting it as a static object on a plinth. The silence of Echakhch’s piece is broken by Lloyd’s installation The Band (2017) that includes a television screen placed on the ground playing footage of a musical group. With only its audio edited and playing in reverse, the camera moves throughout the venue unhinged, as if the filmmaker forgot their camera was turned on.

Prince’s photo collage Bitches and Bastards (1985-1986) is from a series of “gang” pieces where the artist would cannibalize photographs from life-style magazines and place them in a grid. For this particular ensemble, Prince has focused on twelve different hair-metal groups from the eighties. These photographs, originally taken for promotional use, are stripped of their originality. The subversive and androgynous attire of their subjects is lost within this multiplicity. Bringing these numerous photos together makes these musicians anonymous, thus stripping them of their notoriety. These are no longer fetishized rock stars but are now counter-culture conformists. Carpenter similarly critiques this failed rebellion with a portrait of Amy Winehouse from his Decades series. Mimicking the middle-brow aesthetics of a knock-off Warholesque screen print, the work is a hand-painted image of the late British singer-songwriter. The romanticization of music and art often leads to the capital appropriation of their original transgressive purpose. This occurred with Warhol (although he celebrated this sort of usurpation), as well as musical genres like jazz, rockabilly and definitively punk; all of which greatly influenced Winehouse. Winehouse – who once could have been a counter-culture icon – unintentionally became the neoliberal vision of resistance. This irony wasn’t lost on the talented musician, who likely saw this regression as a tragic metaphor for the departure of punk from its original essence, despite having an earnest passion for its message.