by Chris Moore

Uli Sigg describes himself as a mere researcher, belying the transformational scope of his contribution to art and China. For two decades Uli and Rita Sigg have collected “Chinese contemporary art”, forming the largest and most important collection of its kind. In July 2012, the Siggs gave 1,463 works to Hong Kong’s nascent M+ Museum of Visual Culture, including many uniquely important historical works, a donation among the most important to any museum in recent decades. To coincide with the opening this week in Shanghai of the 15th anniversary exhibition of the “Chinese Contemporary Art Awards” (CCAA) at the Power Station of Art, Randian’s Chris Moore spoke at length with Uli Sigg about the history and philosophy behind CCAA, still the most respected art award in China.

Uli Sigg: I always wanted to resolve this [the difficulty of presenting Chinese art to the world] as a person myself, but this proved much more difficult than I thought. This brings us to CCAA. I set it up there but I always felt it should be the Chinese people deciding what meaningful art is—and therefore to put [CCAA] in their hands—but that proved quite difficult. Some think it should be even more associated with my name, and that it would be beneficial to the award, while I thought I should be totally dissociated from it. So now we are somewhere in between. As a procedure, CCAA has been totally disconnected from me—not totally, in that I’m a member of the jury, but I am one of many. For a long time, there is this myth I am the person deciding, but of course I am not.

Chris Moore: What makes contemporary art and what makes contemporary art Chinese?

Uli Sigg: Well, what makes contemporary art is art that speaks to our time and the language is from our time, if not the content. If I searched for one element: representing our time. I mean, we could go on for hours as to what makes it contemporary, but basically either the content or the language is about our time.

When I set up the award, I had several debates. I was preparing the award with Karen Smith, and we discussed whether it should be called the “Chinese Contemporary Art Award”—which is its name now—or “Contemporary Chinese Art Award”. This brings us to your question: is there a “Chinese” contemporary art? Is it Chinese in its essence or just art made by Chinese people? Or is it made in China? Or is it made in the Chinese cultural space? That is the definition I like, myself. So, Chinese contemporary art is art that is made in the Chinese cultural space—you may say, greater China.

CM: That’s extremely wide.

US: Yes, it is very wide.

CM: For instance, that could include someone like David Diao, who has actually spent the vast majority of his life as a Chinese migrant in America.

US: There are some, shall we say, impositions inherently in this, like whether this applies to the whole diaspora. But if it has to come out of someone very close to the Chinese cultural space and accepts to be part of that space, then probably the answer is yes. I had such discussions with people like Gu Wenda. We talked about the fact that a large number of people think that many in this generation of Chinese artists in the diaspora were playing the Chinese card as a very successful strategy in the West. And his response was, “What do you expect me to do? I grew up in China. I spent 28 important years of my life there. I got all my education and my whole background there—do you expect me to throw this away when I move to the States? Even if I wanted to, I probably couldn’t.” On the other hand, I’m not necessarily interested in art produced simply by someone with a “yellow” face. That doesn’t make it Chinese yet! Because some artists, unlike Gu Wenda, left China with a very clear purpose, to abandon their Chinese identity and not have any relationship or be associated at all with China. Maybe that person leaves [the] Chinese cultural space. This probably illustrates what I mean by Chinese contemporary art.

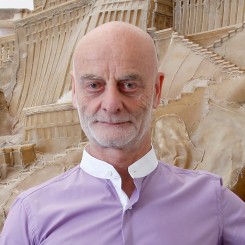

Uli Sigg at home with Shao Fan’s Moon Rabbit, 2010, oil on canvas, dia. 220 cm (image HUG Karl-Heinz)

US: There is this very popular notion of having this global world and national identity not playing a role anymore. I don’t believe in that. For me there still is Chinese art. There is also Swiss art or American art, even though we may look at it as simply contemporary. I understand those Chinese artists who intend to be just one good artist among good artists, and to get away from being perceived as Chinese—there are reasons for it—but in the end you have your cultural roots, your upbringing, and it will always shape your art, and it probably would be wrong to deny that in your impulse for artistic creation. I always think of, say, Richard Prince, who many people think of as a “global” artist—but he could only become “Richard Prince” in the US (I’m thinking of his cowboy and his pop nurses, joke paintings etc). So if you look at his oeuvre, it has a very strong national identity, even though we would call him a “global” artist—what we broadly consider as Western—he still shows strong traits of a national identity. That is highly desirable, from my perspective.

And if we look at Chinese art, you have it departing from a very specific situation and specific look—like in 1979 and throughout the 1980s and 1990s—because the artists led a distinctly different life from their peers in London or New York or wherever. Whereas now, all of a sudden, they have access to the same information and the same books, they are on the internet, they travel and exhibit with other people, so their lives are sort of similar now. So a lot of the art looks alike, but a lot still doesn’t look alike. These are the issues for me, when you talk about Chinese contemporary art; the art is still a reflection of a specific situation—in China, in London, in New York—but it still remains specific to a degree. Thank God!

CM: A good answer. Not everyone gives an answer to that question as good as yours.

US: Yes, for you it is an issue, I guess. It’s just this not to be seen as a mere Chinese artist—“I want to be a good artist!” otherwise there is this fear “I have been invited because of my Chinese passport” or something. I don’t understand it, but it’s there.

CM: Paranoia is part of the artistic condition, isn’t it?

US: And it went from being a disadvantage to be Chinese for so very long to becoming a strong advantage—only in terms of being seen, because then every gallerist, curator, museum director and collector go on pilgrimages to Beijing and Shanghai, so the artists got seen by so many people. If they had been an artist in New York or Berlin, that definitely would not have happened. So it sort of flipped from having been at the periphery of attention to having many opportunities which others don’t have in other capitals of the world. Though of course, the Western world still provides the gatekeepers to the big events—the documentas, Venice Biennales and so on. So we see more balance in the power game than in the past—in the sense that the gatekeepers are still Western, but the Chinese artists get more and more attention.

CM: This raises another problem. Artists from the 1990s—Yue Minjun, Zhang Xiaogang and even Xu Bing—have the problem of being more than mid-career artists. What do they do now? How do they reinvent themselves when China is already very much part of the international art world? I think some of them are struggling. I think Xu Bing is, partly because he is now very much part of the administrative system in China through his role as Vice-President of CAFA. Zhang Xiaogang, I don’t know, but he seems to have drifted a little bit. Yue Minjun has kept clear of these structures, and perhaps he is reinventing himself now—his more recent work I find quite interesting; I’m not popular in saying that, but I think it is. Do you feel this is an issue?

US: I feel that these are two different issues. One is, can you be involved in official China, in the official apparatus, and still maintain autonomy and creativity? Then there is the general issue of the mid-career artist. On the first, it’s difficult for me to comment. I mean, can you have a foot in each camp? I guess you can—some people can, successfully. I wouldn’t want to make a judgment on Xu Bing’s creativity, but it still seems to be there. But if we talk about mid-career artists, then I think this generation you mention, so successful in the ’90s, has this problem, having had very strong ideas, having exploited those ideas fully, and now having to create a second or third idea of equal artistic strength. Maybe we are too demanding in that we expect artists to reinvent themselves a few times in their life. I always think of Morandi who had his ten bottles and painted them for fifty years; we think these are great paintings. So it has to do with our times—which are so demanding that we expect an artist to come forward with something entirely new every few years. Of course, the great artists can do that, but already to have had one strong idea is a big artistic achievement, in my view. It separates them from millions of other artists. Are they able to have a second one, or in some cases a third one or a forth one? I guess they have the personality, but it can take ten years to develop that second strong idea. For the artists it is very difficult to sustain this period, but they all have the kind of artistic personality that any day they could hit on a new idea.

Thirdly, this generation has grown up rubbing against the system, against some very firm beliefs, and all of a sudden it’s as if their enemy has died. Of course, there is still resistance there, but now the system is much more agile. So as an artist, you have to find a new paradigm, and that is not an option in the same way—then you must find another impulse. Cynical Realism came out of 1989 and out of the very specific condition they were in—of being disillusioned, resigned, of not wanting to contribute to this “new” China. That created a very strong movement and a very strong impulse; it was that kind of resistance against which they created art, and now their environment is totally different. If you grew out of that mold of producing art, how do you find a new mold—giving you the stimulus?

I think that this is the broad problem of that generation. Some have found something very successfully, and others haven’t.

CM: Probably out of all of them, Cai Guo Qiang has maintained the greatest flexibility.

US: Yes, probably true. Of course, for a painter, the field is much narrower—probably a more difficult problem to solve.

CM: We should turn to CCAA. What are the origins of the award?

US: I saw all these very good artists in the 1990s, but I saw that there wasn’t an internal debate in China that went beyond the academic circles of the contemporary art world. I also saw that internationally, nobody paid any attention to these good artists in China. I was thinking what I could do to improve that situation. Of course, today it’s hard to imagine that no one knew about Chinese art and that nobody took any interest. Today it’s very different. It’s hard for us to imagine that 15 years ago, this was not the case. Yes, there were exhibitions abroad and now people talk about these exhibitions, but they were mainly in second-tier cities, museums, small places, and they were seen by a specialist public—fans of China, sinologists, etc—but they were not in the big venues. I thought that if I created an art award—since there wasn’t one in China—maybe at some point it would become something like the Turner Prize in the UK. Maybe that could raise interest domestically, beyond the more academic circle, and it would allow me to bring the international big shots to China so that they see the Chinese art and incorporate Chinese artists into their projects. It wasn’t so much that everyone would do a China exhibition. It wasn’t even about who is winning. But they would see the artists and things that they liked, and they would show it abroad. These two reasons—and both worked, in a way.

CM: To create a platform within China and, secondly, to create a destination.

US: Attention and opportunities outside China. That worked very well and very quickly, with the likes of Harald Szeemann, as the first, bringing 20 artists to the Venice Biennale in 1999 after he had been in the jury and I had traveled with him and visited many studios together.

CM: I didn’t realize that.

US: Yes, that’s the only reason! He did several trips and jury meetings on his first trip in 1998. I think in January 1999 he was appointed to do the Biennale, so he only had about six months to organize it—in the jury 1998 he had seen a lot of Chinese art and that made him decide to give such a platform to Chinese artists. (1) Plus there’s a big difference between the 1993 and 1999 Biennials. Of course now with Johnson Chang, the 1993 Biennial is back [in the news]. It was the first time not that China had a pavilion but that China came back as a competitor. But that pavilion—I saw it—was in the remotest part of the Giardini—you know, like where Yugoslavia and all this was. I saw it maybe two months after the opening and there were not even doors on the building. It was just the worst thing, and nobody went there. The Chinese [artists] were very excited, and I think it was Armani [the fashion designer] paying for the whole thing—it wasn’t something official, it was an “Armani” pavilion, paid for by Armani—and very shabby, very poor conditions. Very good works, though, but nobody saw it. Whereas in 1999, Harald Szeemann was the first one to open the entire Arsenale (2). This was the first time the Arsenale had been part of the Venice [Biennale]. So the big international public—who would never ever go to a Chinese art exhibition—for the first time had to walk through the twenty artists. They had no choice! That’s the difference with the past. So all the big professionals, museum directors, institutions, collectors, who never ever looked at Chinese art, all had to. That is why 1999 was so important.

But that was just one exhibition. There was also Alanna Heiss of PS1 [the founding director]; she showed Chinese artists. Chris Dercon [now director of Tate Modern] showed Ai Weiwei in Munich, Ruth Noack showed Lu Hao, Xie Nanxing, Hu Xiaoyan and Yan Lei in DOCUMENTA 12 and so on. So many, many results came from the various jury members.

CM: CCAA works on a two-year cycle, with one year for art and one for writing. Why do you also want the prize to be for art criticism?

US: I always thought of CCAA as a tool to contribute to the “Chinese art operating system”, as I call it. Each nation has its art operating system consisting of galleries, museums, art critics and artists, collectors and so on. I could see this very interesting art operating system emerging in China—this is why I consider myself as a researcher, not so much a collector—and that’s why I thought an art award would be a very useful contribution. If we see it as a tool, I thought another issue that needs more attention is art criticism. Again I hoped that through creating an award I could contribute, not to solve the problem—I cannot do that—but to create attention and put it really on the agenda. There is a need for independent art critique. In the past, there was no independent art critique because of censorship throughout the 1980s and 1990s—you had magazines, but of course there was a lot of ideology there and people couldn’t write freely. Then came the market and it became so strong in China that the auction catalogues would say what good art is and what bad art is. The collectors got their information through the auction houses, and maybe some gallerists, but basically through the market. Naturally, the market is also very strong in the Western world, but it is balanced by the institutions, like the museums and so on who can do their shows—which they cannot do in China the same way—and through independent art critics. This balance is quite lopsided in China, because while art critique was dependent on political issues until the 2000s, all of a sudden the art critics had to write many, many books for the artists, which all of a sudden started to appear. This created another type of dependence. You can’t write a book for the artists and be really independent. That is a contradiction! So one dependence was being replaced by another dependence. As you experience [as an independent magazine], it’s just very difficult to survive. It’s not that these people are not interested in being independent art critics, but how can you survive in this environment as an independent critic? For all these reasons, I thought such an award would bring attention to the situation and, as a by-product, maybe allow a piece to be written that probably wouldn’t be written, because the market wouldn’t pay for it. If you think of the first winner, Pauline Yao, writing about what I call the “semi-industrial production methods” of Chinese artists, I think this is a topic the market and the galleries wouldn’t finance. In that sense, a piece can get written that otherwise wouldn’t have been. I also still see it as a tool to point to other issues in the art operating system of China. It’s a good tool, I think, an award—create some attention, some publicity, maybe even create some solutions. So, there are many more issues we could look at with an award.

But of course, I have my limitations. So far, with few exceptions, I have paid the bill. There is a limit to what we can do for financial reasons. We did get sponsorship from M+ for the last years and in the past, from time to time, we got a little sponsorship contribution. I was always hoping I would find Chinese institutions, Chinese collectors, individuals, media, whatever, and I would be so happy to hand it over to them. It shouldn’t be a “Uli Sigg” thing—I’ve said this so many times! But so far it hasn’t happened. I am convinced it is a very good concept—not because I created it!—but because it is really a very useful thing to develop the Chinese art operating system in a good way, since it creates debate and contemporary art is about this: It ought to exist in order to debate, to develop through a debate, to find its place through a debate. That place, of course, is a dynamic issue. It’s not exactly, “so this is the winner”; it is more why is this the winner, or why would other people not consider this to be the winner? It is really about this. Whether or not “so-and-so” is the best artist in China is not the point, but why could this artist be considered the best? I think we have contributed much to this debate.

CM: There are other awards too, now, but the award that really counts is still CCAA.

US: This is precisely the case because of three things. Firstly, it is totally independent. It’s not tied to a company name. It would have been very easy for me to bring in a sponsor or someone to foot the bill if I were to allow a name other than CCAA, but this would then create some dependency. Also, there are absolutely no ties to an artist. With other awards, the winner must donate a work. It’s a very mixed blessing when the winner is obliged to give them a work! With CCAA, there is absolutely no obligation upon an artist. He just gets the prize and that’s it. Thirdly, it’s an academic jury. It is a purely academic jury in the sense that very important people of the art world— whether it is Harald Szeemann, Alanna Heis, Chris Dercon, Ruth Noack [documenta 12 curator], or Hans Ulrich Obrist. Then there are the Chinese jurors who all have weight in the Chinese art scene. I try to bring in the people who will do the next big thing, so that they can see the Chinese art before they do it. This has had a big impact. If you take the documenta of Ruth Noack, there were 7 or 8 Chinese artists. If you take the last documenta, the curator, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev was not introduced, let us say, in a systematic way to Chinese contemporary art, and so only two Mainland Chinese artists were included. It made a difference. Actually, she was a jury member after documenta. I invited her to participate, to get to know her. But it makes a big difference—it means twice as many Chinese artists in documenta and the Venice Biennale, because somebody recommends them. So the jury is very important to me. I want it to be half Chinese—Chinese experts—and the other half international experts.

CM: What are your hopes for CCAA’s future?

US: Well, I hope it will take up a place in China like the Turner Prize has done in the UK in setting an agenda for debate, in magnifying the agenda for debate. I would hope for more Chinese people participating in the running of the award. CCAA is not to do with me. It is there for China…And more awards under CCAA, because there are still topics that need debate in China.

Endnotes:

1. “[Szeeman] became the first curator to include multiple contemporary Chinese artists in a traditionally Western-oriented institution. He also juxtaposed more well-known artists with up-and-coming ones in the same spaces. In order to achieve his vision, Szeemann pushed for the elimination of a previously set age limit to exhibit in the Biennale.” Melanie Tran, “Treasures from the Vault: Harald Szeemann’s ‘Project Files’”, The Getty Iris, May 31, 2013 [link here]

2. A sprawling 45-hectare shipyard and armory complex dating from 1104. Szeeman “supervised the partial renovation of the historic Arsenale complex, which includes the Corderie and Artiglierie, to be used as exhibition space. One of these buildings was designated for artists whose identifying nations did not already have pavilions of their own…” Op cit.