As prescribed by the normal relations of the contemporary world, the human body is often characterized by a sort of “stable sanctity.” The body becomes a signifier for the completeness of “humanity.” Ancient forms of punishment that involve bodily dismemberment were considered “inhumane” and thus abolished. In comparison, in the effort to challenge norms regulating common conceptions of humanity, many contemporary artworks often take up “dehumanizing” positions to rework, deconstruct, and reconfigure the human body. Due to different levels of understanding, these artists operate on vastly different logical frameworks when reworking the body. When it comes to mutilating the body, while some only hope to express sacrilege, some might engage with meanings intimately tied to long-standing and complex forms of religious sentiments and civilizational structures. If the “body” is thought to be a crucial subject for artmaking in the “posthuman” era, it is then particularly necessary to decode the many layers of cultural symbols and value judgments attached to the act of “bodily dismemberment.”

“Dismemberment” narratives are common occurrences in ancient religions and myths, and often represent profound metaphors for the disintegration of the status quo and the birth of a new sacred order. In Babylonian mythology, the new god Marduk defeated Tiamat, the goddess of primordial creation, severing the latter’s body in half to create the heavens and earth. In the Rigveda (an ancient Indian collection of hymns), Purusha’s body was also dismembered by various gods to give birth to the world. Osiris, the Egyptian god presiding over the land, was cut up by Set and subsequently put back together by Isis, the female deity of life, ultimately becoming the ruler of the underworld and all living things.

Generally speaking, this series of myths and religious narratives common to regions in Mid-Western Asia often attests to a strategy for depicting historical “events.” The dismemberment of a corpse is a remarkable way of performing sacred rituals that comment on the passage of time. It is the ritual that constitutes the significant “event” that symbolizes old orders giving place to the new. In mythological history, the “event” is a crucial nodal point, the space-time surrounding it and the corresponding states of existence will necessarily undergo a fundamental “transformation.” As the unit that preserves the conventions of human existence and experience, the body, and the disintegration of this body, brings about a strong commemorative significance for this kind of “transformation.” Therefore, the body itself becomes the archetypal carrier symbolizing the sacred order.

The ritualistic disintegration of the human body signifies the disintegration of the order in which the individual exists: such a breakdown either implies the construction of a higher order of existence, or indicates that the authority of higher orders has encountered a state of crisis. For example, the public execution of criminals internal to one’s own tribe is conducted in the aim of providing a positive visual demonstration of power; conversely, the execution of the leader of enemy tribes could threaten the entire juridical system of the enemy tribe.

In this respect, the sacred character of the “event” in Abrahamic religions appears to be the most pronounced. As long as one has some understanding of biblical narratives, one will find that from the point of view of the Judaism, history itself is almost directly equated with consecrated “events.” For example, in “The Book of Leviticus,” (the third book of the Hebrew Bible) a Levite took the corpse of his wife, who was raped to death by foreign tribes, divided it into twelve pieces, and sent them all over Israel to rally a call for vengeance. The moral of the story is that, through the morally-offensive act of dismembering a body and presenting the brutally mutilated corpse to Israel’s various tribes, the Levite attempted to stir up the latter’s sense of indignation against these evil deeds. As shown by the display the bodily dismemberment, which constitutes an event, the scattered Israelite tribes were able to come together and execute military action “as one.” The symbolic disintegration of the corpse corresponds to the realistic convergence of political units—which is the core message delivered by the Levites’ story.

In the Old Testament, the power of God was often demonstrated through the damage and slaughter of the earthly body. As God created the human body with soil, from his perspective, the breaking-apart and destruction of the human body is nothing more than the crumbling and diffusion of soil. Whether it was Abraham’s sacrifice of his own flesh and blood, or the sickness and catastrophe inflicting Job, these “events” all demonstrate God’s invincible power and reveal its connections to the human realm. In this sense, Abrahamic religions adopt an attitude that debases and controls the body in exchange for the favor of God. Even in the system established by the New Testament, this attitude persisted. Just like Paul prescribed, all Christians ought to have the following understanding: “I see in my members another law waging war against the law of my mind and making me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members. Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death?”[1]. To this the right answer should be: “To set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the Spirit is life and peace.”[2]

Christianity’s privileging of the “spirit” over “flesh” would have profound impacts on the world to come. The “flesh,” then, becomes essential for determining whether the “flesh” could be reconstituted. In the Grimm’s fairy tale of “Brother Lustig,” there is a story about a dead princess who was resurrected by St. Peter. His method involved cutting up the princess’ corpse and boiling it so that the flesh and blood melted away and only the bones remained. He then invoked God’s name to regenerate the flesh and thereby resurrect the princess. Later, when Brother Lustig attempted to replicate this magic trick, he failed because of his impiety and ignorance. Understandably, since the Middle Ages, this tale had already incorporated many folkloric elements within it. The journey to heaven that the cunning commoner Brother Lustig undertook under the scrutiny of St. Peter is intrinsically connected to the metaphor of resurrection following dismemberment—it not only reflects Christianity’s belief in human resurrection, but also the philosophical basis upon which alchemy (which had its roots in Greco-Egyptian natural philosophy) and its belief in the transformation and sublimation of humanity was founded.

Whether revealed religion or alchemy, both attach specific philosophical meaning to the “event” of “bodily dismemberment,” forming a sacred ritual that sees the the act of dismembering and restoring the body as a way to sacrifice the “self” that exists in the present to greet a higher dimension. It is a process that moves from “diversity” to “unity.” With regards to alchemy, bodily dismemberment and reconfiguration are also extremely important symbols. For a small number of alchemist-scientists, the cutting-open and dissolution of the flesh is an inquiry of natural philosophy, as well as a new method for cultivating self-consecration/sanctification. Rabelais, the author of the now famous Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel, had been a follower of Hermetic Alchemy and esotericism, and even secretly dissected corpses.

By dissecting corpses and grasping the essential secrets of the body, the proto-scientific practice of alchemy further dispelled the mystique of bodily dismemberment rituals, thereby rendering the sacred “event’s” domination over the body ineffective. Moreover, medical experiments on the body would come to challenge the religio-ethical foundation established by the Vatican, as well as the everyday habits of ordinary people. However, with the advent of the Enlightenment, bodily dismemberment gradually obtained juridical legitimacy by way of “seeking the truth,” and with it came the dismantlement of the sacredness that Christianity ascribed to the “event” of bodily dismemberment. In the West today, the body, no longer marked by a rigorous sense of religious solemnity, is merely an emblem for the vulnerability of “humanity.” Since “humanity” is a metaphysical concept, the body then becomes an empty canvas that could be disrupted and “revolutionized” at any time. Displays of individuality, such as piercings and tattoos, or masochistic acts of self-desecration, are drained of any force. Especially in today’s time, where bio-engineering, artificial intelligence, and virtual technologies prevail, the human body is understood to be an assemblage of desire and capital, stooping to the level of a thoroughly materialized subject and a platform for experiments. Neither is it capable of entering into a unified sanctity nor could it be sublimated by processes of alchemy. This precisely corresponds to what Nietzsche foresaw as “decadence,” the fundamental symptoms associated with the complete loss of vitality.

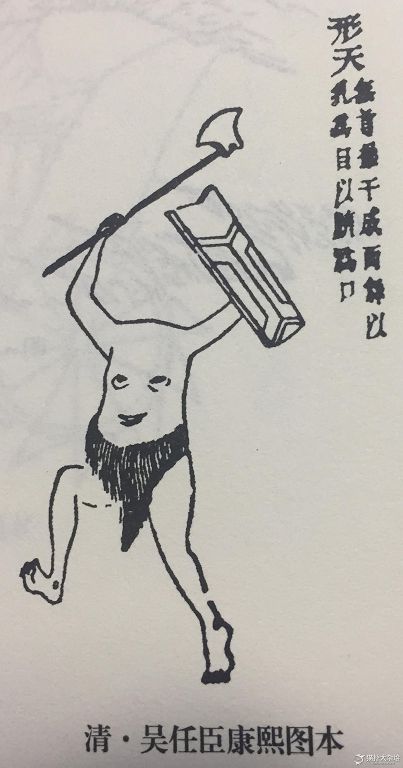

Corresponding to the Western concept of the sacred “event” and the subsequent birth of the natural body, is the Chinese concept of “bodily dismemberment.” Mythologies featuring the dismemberment of gods and deities are quite common in China: whether the transformation of Pangu and Nuwa’s remains into the foundational elements of the earth (his breath became the wind, his eye the sun etc.), or Chiyou and Xingtian’s ability to maintain consciousness and continue fighting after being decapitated, these tales are still spread and eulogized today. It is of note however, that Chinese traditions of bodily dismemberment are often deeply interwoven with Taoism and Taoist notions of “qi” (subtle energy).

Taoism has consistently placed emphasis on remolding the human body. In fact, the so-called idea of “becoming immortal” carries noticeable characteristics of bodily experiment, for which the encompassing logic is as follows: the dissipation of earthly flesh is the necessary cost of ascending to a higher mode of existence. In Taoism immortals are referred to by the term “尸解仙” “shijiexian” which translates as “the corpse being untied or emancipated and transforming into an immortal” — a state of existence achieved through Buddhist spiritual practice which is characterized by an absolute “vaporization” of the body. The classic Dong Zhen Cang Jing Ling Xing Shen Jing洞真藏景灵形神经 states that: “There are many ways of untying the corpse to bring the dead back to life; for those who die from decapitation, their spirits have escaped from the side. For the dead who have not yet been buried, their bodies have already disappeared. There are, ones whose form seems to remain yet whose bones cannot be recovered, ones whose clothes remain yet their forms have dissipated, ones who hair remains yet their form is gone.” Ultimately, the self-cultivation and transition towards “immortality” are necessarily accompanied by the destruction and scattering of the human form. This shares affinities with alchemy’s understanding that material forms need to be divided into individual elements and then put back together. That is because Taoism, like alchemy, belongs to the realm of natural philosophy, and not religion.

Although Westerners were able to take the logic of the “events” in religion, alchemy in natural philosophy, and merge the two into folklore and mythological tales, this provokes the emergence an evident tension: in religious rationale, bodily dismemberment is in itself a sacred “event,” not a conventional state of existence; yet alchemy views the “event” as a categorizable and summarizable “principle”—a means to reach higher modes of existence. Thus, the latter will inevitably clash with theology’s prescription of ethics, morals, and taboos. In China, however, the orthodox ritual system itself often draws sustenance from the credo of the natural body and surrounding“qi” and with that gave a theoretical foundation grounded in materialism and the natural world, to the ethical formulation of the dispersion and reconstitution of the body’s “qi”— the practice of “Taoist methods” could peacefully coexist with everyday earthly life.

In both the Taoist and Confucian theory surrounding cultivation of the mind, the process of administering of the body’s“qi” entails a way of life that not only stems from nature, but also applies to the normative world. One who takes up this approach in cultivating the body and mind has to go through a series of exercises, to be transformed into an exceptional being endowed with sacred qualities. In this process, the dispersion and eventual destruction of the flesh, brought about by external causes, becomes instead a new round of justification for sacred existence: despite damages done to the earthly limbs,“qi,” along with its implicit messages regarding “inner morality,” is far from destroyed, emerging with a greater clarity and purity. As such, the Confucian notion of to “die in a virtuous act” shares common ground with the Taoist notion of “abandoning the earthly body for immortality”: both see the destruction of the body as that which makes higher forms of existence possible. In this sense, compared to the Western conception of the sacred “event,” in which one passively receives divine will, Chinese narratives of bodily sacrifice aim to demonstrate the sincerity and loftiness of the “temperament” that encourages individuals to be actively incorporated into the vast cosmic truth. It is not God’s will that is manifested by features of sacredness, but rather the very subject who practices morality. The dismemberment of the “smaller self” reflects the permanent will and vigor of the “greater self.” The abandonment of the corporeal body’s conventional order makes way for the condensation of “qi” on a higher-dimension. Yet this flow of energy belongs to both “heaven and earth,” and the “self.”

The best example for this is none other than the vaporization-consecration of the body of the warrior Guan Yu. “The death of Guan Yu” embodies typical traits of bodily martyrdom in Chinese narrative history. In folklore legends, Guan Yu was murdered by treacherous soldiers on the battlefield. Like Chiyou and Xingtian, he became a deity of the underworld. Transcending life and death, this image of someone whose courageousness cannot dissipate, in fact underlines the constancy of the “spirit of loyalty.” By cherishing the “spirit-image” of an ancient hero Guan Yu, who was granted the title as the Marquis of Hanshou, people placed hope in secretive methods such as folktales and divine worship to educate future generations on fundamental ways to obtain “righteousness” and “self.”

The consecration of Guan Yu’s image among popular worship and artistic activities goes to show that, while China’s unique concept of the “spirit-image” (which has its foundations in Confucianism and Taoism) has helped sanctify narratives of bodily dismemberment, it also made room for a more stable naturalized explanation. While the vaporized body ensures the operation of the divine structure of power, it prevents this structure from being easily swayed by an “eventness” that relies on the arbitrary will of a monotheist God. By stressing the collective participation in orally spreading the traditional genre of “historical romance,” (in which imitating and respecting the everyday practice of ancient heroes precipitates the realization of a stabilized “spirit-image” ethics) the age-old myth of “bodily dismemberment” was given a more congenial character, and assimilated into an everyday ethical practice and ruling experience in Chinese history. This is not to say that “spirit-image” has hereby lost its sacred character. On the contrary, sacredness became a gate to enlightenment that ordinary people could experience, reference, and learn from.

When compared to the Western logic of the human body based on the sacred “event,” the openness and naturalness of the Chinese “vaporized” body becomes more pronounced. Both forging connections between “disintegration” and “consecration,” the Chinese way of understanding the flesh-and-blood body as the gathering and dispersion of “qi” and the birth of the “spirit-image,” contains an astonishing sense of political wisdom. As such, it was able to skip over complex questions surrounding bodily ethics that Westerners cannot avoid in the confrontation between revealed religion and natural philosophy, thereby inspiring future generations to create images of art imbued with more vitality and power.

-245x245.jpg)

-528x581.jpg)

以莎乐美故事为主题的《施洗约翰的头在显灵》.jpg)

《人体构造》中的人体解剖图.jpeg)

-528x765.jpg)