She emerges and disappears, paint swirling and eddying, pigment lush and thick. She is familiar to the painter. He has painted her dozens of times. Day turns to dusk. He puts down his brushes. Unsatisfied, he scrapes off the day’s work. She must come again, another day. It was the same last time and all the times before.

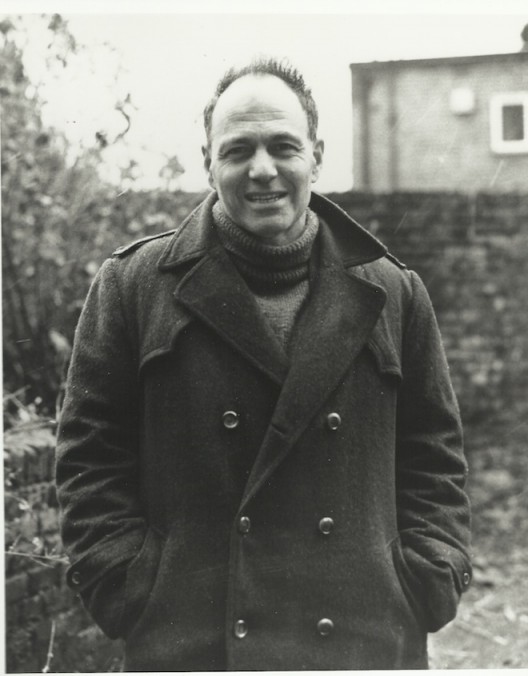

Frank Auerbach (b.1931, Berlin) has been a painter for almost 70 years. His free, energetic, impasto style of painting has led him to be described as “Expressionist” but this is a misnomer. He does not seek to represent a subjective psychological state or materially respond to notions of existentialism. Auerbach’s task is more Sisyphean.

Each day Auerbach goes to his studio in Camden and paints. Espousing a practice of repetition, he paints only portraits – often the same people – and scenes from Camden. The aim is to capture time—a place, a person, a view. What is painted on one day is a summation of a brief moment in time and space. It is not about expressionism but experience. If there is an artist equivalent living today in the West, then it is probably Alex Katz, albeit with a different aesthetic, one more centered on capturing an instance in a certain light.

Head of Catherine Lampert, 2015, oil on board, 56.5 x 51.4 cm.; 22¼ x 20¼ in. Copyright Frank Auerbach, Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

Stylistically, it is deceptively easy to find equivalents to Auerbach. The “style” of an artist in some way includes technique but is not limited to it. It becomes part of their familiar visual signature or “voice.” Concentrating on style or technique too much though, confuses the cerebral basis for employing it, making it seem like a coat chosen on a whim, and quickly turning words like “Pop” and “Expressionism” into trite clichés. Some Abstract Expressionist painters, such as Willem de Kooning (1904-1997), used gestural freedom and timing in a way similar to Auerbach but stylistically, de Kooning’s conceptual tools are fundamentally different. Whereas the Ab Ex heroes were engaged with a surface-battle against “theatricality,” as Michael Fried argues, Auerbach as well as artists as diverse as Katz, and going back, even van Gogh, focus their critical eye and hand on creating an equivalence in paint for what they see—really, witness—, even for themselves, as painters.

Mornington Crescent- First Light, 1989-90, oil on canvas, 134.9 x 112 cm.; 53 1/8 x 44 1/8 in. Copyright Frank Auerbach, Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

None of these artists are stylists though, in the sense of being puppets of a certain look, even if one of their own design, whether we speak of van Gogh, de Kooning, or another Abstract Expressionist, Hans Hoffmann (1880-1966), or in China, say of Zhu Jinshi (b.1954). In each case here, the paint, its physical weight and material presence, is not working as a representational medium but stands directly for the artist’s vision, which is the same as the artist himself. And with the exception of de Kooning, neither is it egotistical. On the contrary, it is lonely and personal. The question is not a public, “Who am I?” but a private, “How do I see?”, being the precursor to the more general “What is a person?”.

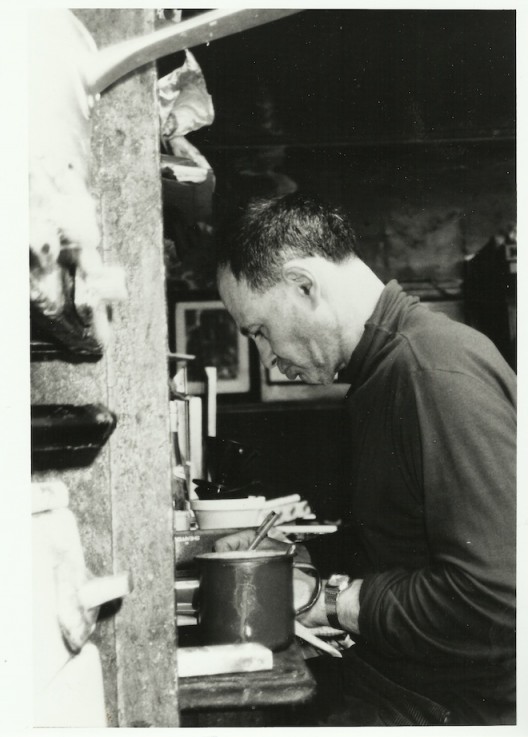

Frank Auerbach was born into a middle-class, Jewish family in Berlin. His father, Max, was a patent lawyer and his mother, Charlotte, trained as a painter. In 1939 they sent Frank, aged 8, to England to escape rising Nazi persecution. Frank did not see his parents again. In 1942, they died in a concentration camp.

Frank Auerbach went to school in England and in 1947 took British citizenship. The following year, he began his formal art education, studying first at St. Martin’s School of Art (1948-1952) and then the Royal College of Art (1952-55). During this time, 1947-1953, Frank and a fellow St. Martin’s student, Leon Kossoff (b.1926) took additional evening classes at London’s Borough Polytechnic with one of the leading British artists of his generation, David Bomberg (1890-1957), who would teach Auerbach, put simply, the value of freedom and spontaneity in painting. Following graduation, Auerbach began teaching, first at secondary schools and then at art schools, including the Slade and Camberwell School of Art. In 1956 he had the first of several solo shows at the then influential Beaux Arts Gallery. In 1964, Auerbach moved to Marlborough Fine Art, where he has remained ever since. Auerbach has had two particularly important retrospective exhibitions. The first was at the Royal Academy in 2001. The second was a joint exhibition at Tate Britain and the Kunstmuseum Bonn from 2015-2016. Following David Bowie’s death in 2016, Auerbach’s “Head of Gerda Boehm” (1965), which the Hollywood actor, David Niven, once owned and which Bowie had bought at auction in 1995, was sold for £3.8 million. Gerda Boehm is a small oil-on-board work, measuring just 44.5 x 37 cm. Gerda was an older cousin of Auerbach and the only family member he saw after the end of the war. She sat for him numerous times from 1961 to 1982.

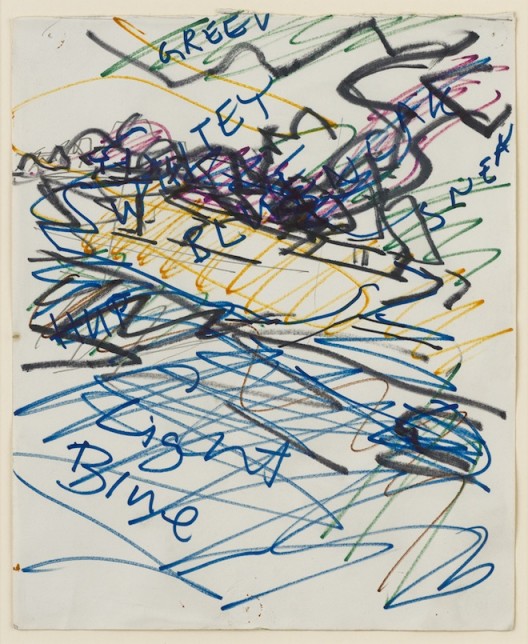

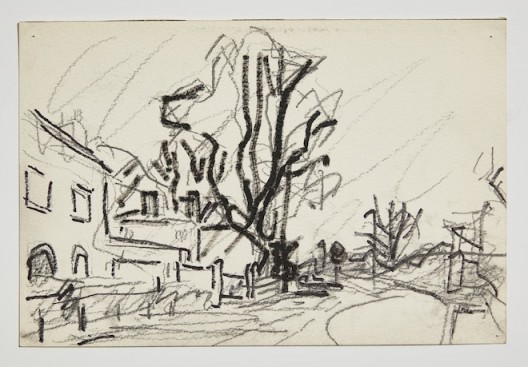

Study for “To the Studios 1990-91″, 1990, black ink and coloured crayon on paper, 34.3 x 29.7 cm.; 13 1/2 x 11 3/4 in. Copyright Frank Auerbach, Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

Perhaps the best description of the effect of an Auerbach painting on someone, comes from David Bowie:

“I think there are some mornings that if we hit each other a certain way—myself and a portrait by Auerbach—the work can magnify the kind of depression I’m going through. It will give spiritual weight to my angst. Some mornings I’ll look at it and go, ‘Oh, God, yeah! I know!’ But that same painting, on a different day, can produce in me an incredible feeling of the triumph of trying to express myself as an artist. I can look at it and say, ‘My God, yeah! I want to sound like that looks.’… I find his kind of bas-relief way of painting extraordinary. Sometimes I’m not really sure if I’m dealing with sculpture or painting. Plus, I’ve always been a huge David Bomberg fan. I love that particular school. There’s something very parochial and English about it. But I don’t care. I like Kossoff for the same reason.”2

David Landau Seated, 2016-17, oil on canvas, 56.2 x 51.4 cm.; 22 1/8 x 20 1/8 in. Copyright Frank Auerbach, Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

There is no ‘key’ to these paintings: they are not meant to be unlocked. The questions raised are for contemplation, not explication. The palpably physical accretion of pigment forms the ‘skin’ of each painting. More or less similar technical means have been employed by artists as diverse as Georg Baselitz (b.1938), Zhu Jinshi (b.1954) and Li Songsong (b.1973). The means of painting, though, speaks to a more Modernist and novelistic tradition: the experience of time. Each Auerbach portrait does not represent a personality per se; each picture is Auerbach’s rather than, foremost, a portrait or a caricature, a notable constant of many portraitists. At the same time, each figure is a person: real, temporal, corporeal and mortal. Each painting is an attempt to record humanity, in both senses of the word. The task would be familiar to Proust, Joyce, Mann and Mansfield, and indeed in many ways Auerbach himself could easily be a character from one of their novels. The diurnal process of repetition and expungement speaks to something more specific though and this is where things get really interesting.

Study for Tree on Primrose Hill, 1982, black ink and coloured crayon on paper, 21 x 27.5 cm.; 8 1/4 x 10 7/8 in. Copyright Frank Auerbach, Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

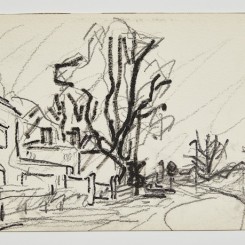

Park Village East, 1998, black ink and crayon on paper, 20 x 29.8 cm.; 7 7/8 x 11 ¾ in., entitled, signed and dated on reverse. Copyright Frank Auerbach, Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

If you want to slow time down, to make it plod, to stretch a summer vacation out as far as possible, one must do the same thing each day, in the same order, every day, so as to be totally engrossed in the activity. A painting does just this, freezing a moment in time, whether we think of Chardin’s boys blowing soap bubbles or, less whimsically, Van Gogh’s potato eaters even. Every day is the same picture of that day, that moment. Auerbach’s paintings are all about this slowing of time, of pinpointing time in a certain space. Consider the paintings, extant and destroyed. Not one is the same and each went through many fashionings and stages before it reached, at day’s end, its ultimate end; with one door leading to effacement and the other leading to its existence as a finished painting. Google images, like Borges’s extraordinary Aleph, is a type of map of time and space. And in a small branch of it are many paintings by Frank Auerbach. Some brown like wet clay, others seemingly wrought of ribbons of colour. Sometimes the paint is more mobile, sometimes more constricted. Frequently its mass becomes almost sculptural. Different periods and sitters are depicted—dates are important, of course, but sitters are often reduced to mere initials—and each picture represents one day, one engagement in time, and Auerbach’s impossible but obtuse and determined attempt to stop it. Yet despite the plain absurdity of trying, reflected in these works are moments where he succeeds.

Auerbach’s painting, like Proust’s writer, embodies the act of capturing time. Each day he seeks to capture, according to his style and through a poised coordination of hand and eye, not a particular person but a person at a particular moment in a particular place, the time and space of Frank Auerbach’s studio in Camden Town, a mixed corner of a vast city. In truth, every one of the paintings is the same, but lined in a row from start to an un-finished finish, not one would appear the same as any other.

Albert Street IV, 2017, oil on board, 38.1 x 38.1 cm.; 15 x 15 in. Copyright Frank Auerbach, Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

The paint itself has a weight: specifically, each painting is heavy. The oil pigment often goes right to the edge of the board, splurging off the sides and swept over the edge of the support, emphasizing the sense of the painting as hovering in space, a mass of paint hanging off a wall. Like the manner of their making, the materiality of the paintings attests to their realism; in a sense, guarantees it (not unlike Lucian Freud’s meaty bodies) but we should beware of the hubristic sentimentalism that can inspire. Better to understand the realism here as drawn directly from the reality of the experience of the situation from which it emerged, that being Frank Auerbach’s close observation, examination and exploration of a meeting taking place in his studio or his experience of a scene in Camden Town. The medium is indeed the message and the painter Auerbach fully intends to slow time down, to freeze it forever in one of its many iterations, to find the perfect equivalence in paint for people, and to realize that in the dark space of a studio in Camden, the Aleph contains infinite multitudes. In fact, to behold them.

Albert Street, 2016-17, oil on board, 38.1 x 38.1 cm.; 15 x 15 in. Copyright Frank Auerbach, Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

Notes

*The title of this article is taken from Jorge Luis Borges “The Aleph” (1945), translated from the Spanish by Norman Thomas di Giovanni in collaboration with Borges.

1. Frank Auerbach: Paintings and Drawings 1954-2001, Royal Academy; Frank Auerbach, Kunstmuseum Bonn, 4 June – 13 September 2015 and then London Tate Britain, 9 October 2015 – 13 March 2016. Also see T.J. Clark and Catherine Lampert, Frank Auerbach, London: Tate Publishing, 2015

2. Quoted in Michael Kimmelmann “TALKING ART WITH/David Bowie; A Musician’s Parallel Passion” New York Times, June 14, 1998.