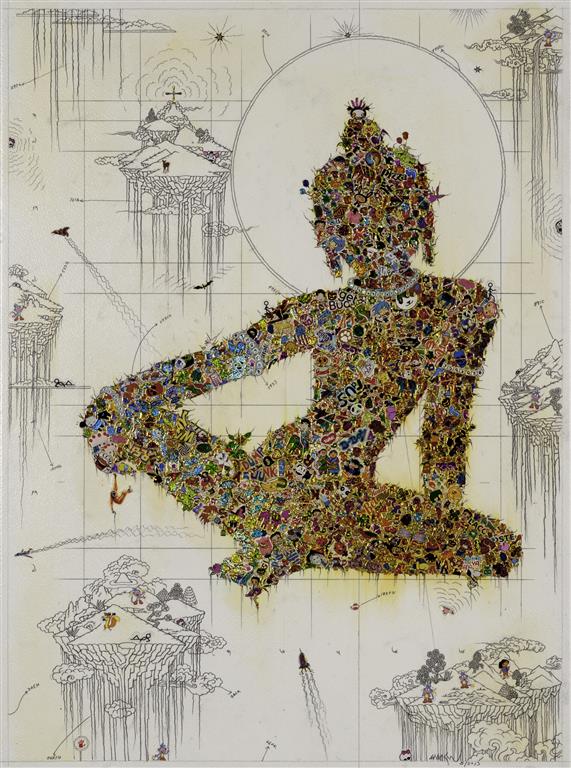

Born in Tibet, the artist Gonkar Gyatso relocated to London where he could more freely express himself. He does not shy away from confronting pertinent social issues happening in Asia, reinterpreting them in a playful style. His recent exhibition at Pearl Lam Hong Kong highlighted recent works featuring popular phrases in mainland China, as well as his twisted versions of statues of Buddha. We caught up with Gyatso at the gallery for a chat about this exhibition and his complicated identity.

Tsao Yidi: Are these all new works in this show?

Gonkar Gyatso: Yes. Some of them were done in 2007–2008—the Buddhas; the new series from past two years are those with Chinese phrases.

TY: How did you start the Chinese Phrase series?

GG: I grew up in Lhasa; apart from Tibetan, I speak Mandarin as my mother tongue. I really like Chinese culture, since I studied Chinese paintings and calligraphy; I use Chinese a lot. Whenever I create anything. I try my best to expand the range of the audience. So I create art in the languages I use frequently, including English and Chinese.

TY: Languages carry cultural and social baggage. By creating art in Chinese, are you asserting your views on social issues in China?

GG: I don’t know who came up with all these phrases like “gutter oil,” “poisoned rice” etc. Of course, they were all circulated on social media. Then I found that politicians in China are also using them in their speeches. For instance, “laohu” (tiger) has been used by President Xi Jinping to describe big-shot corrupt politicians. People are normally scared to touch them because they are quite dangerous. He also came up with “cangying” (flies) to refer to lower-level corrupt politicians, all the “small fry”—easy to deal with, but so so many of them. These phrases are used instead of the normal banal official language; they are easily received by the rural population. Xi is the second leader to have done that; the first was Deng Xiaoping, who came up with famous phrases like “It doesn’t matter whether a cat is white or black, as long as it catches mice.” That was in the late 80s, when China was undergoing social changes and struggles, and people could grasp the idea easily.

TY: Do these names disguise the nature of the objects or phenomena?

GG: That’s it. That’s what I’m fascinated by. It’s almost like camouflage. The horrible things camouflaged under seemingly harmless, interesting names.

TY: Where did you gather all of these words?

GG: I lived in Chengdu for almost six months last year. I read newspapers, watched the news and then searched for them on social media. On the Chinese internet, you can find an annual list of the most popular phrases—“tigers,” “flies,” “gutter oil” and so on. When I was living in China and Tibet more than 20 years ago, it was a very rigid communist society. But now, even though the communist structure remains, a lot of changes have taken place.

TY: So you think it is a good sign that all these reforms are happening in China?

GG: Yes, of course—even though there are many people complaining that it is too slow, or that there is no democracy. It might take a long time to get there. Life is more interesting. I was born in the 1960s and went through the 1970s, 80s and early 90s; in those days, China was quite boring.

TY: How do all these changes affect your works? And combined with your experience of living in the West?

GG: I left Tibet many years ago, but I’ve always been interested in what is happening in Mainland China. I started going back to China in 2004. The changes are quite amazing and I am quite positive about the future, remaining hopeful, especially when it comes to Tibetan situation. At the moment, it’s still tight and tense. For instance, returning to Lhasa takes up a lot of procedures for me—I need to get a special entry permit and go through an interviewe, since I have a UK passport. But one of my dreams is to be able to set up a studio in Lhasa. I am doing this in Chengdu because it’s the closest city to Lhasa outside of Tibet. It’s a bit sad, but what can I do? I should recognize that different countries have different policies and rules and I respect that. The thing is that I have to be careful about not saying things that anger the government because otherwise they could just stop me from going to China. I am very careful about it.

TY: What about these phrases you chose to work with this time?

GG: A lot of them came from the mouths of the Chinese leader, like “tigers” and “flies”; others like “gutter oil” and “haze” are in the public domain. If somebody tries to link them to politics, though, that’s their problem. I’m interested from the angle of how language is being used by politicians to simplify and deliver their message. “Gutter oil”, for instance: I’ve only been in Hong Kong for two days and suddenly realized that it has become a big topic in Hong Kong. What a coincidence! A couple of months ago when I first started the works, I couldn’t have predicted everyone would be talking about it now, outside of the Mainland. Who knows? Maybe “gutter oil” will be in America, too.

TY: These phrases you chose are quite negative—they all reflect the darker elements of society that people don’t want to see.

GG: Yes, they are the dark side. But when you look at my works, they are all cheerful and colorful, shining and glossy. That’s what I saw in China. People have a lot more money, and you can really see it everywhere in China—in restaurants, in hotels, in shopping malls—everything is so glossy. That’s something that I want to present in my work; I am trying to camouflage the dark side to make it look pretty. I also applied Chinese-style decorations during Chinese New Year, the upside-down “fu” (luck) on a piece of square paper. Basically, I’m trying to make contrasts between the festive atmosphere and the meaning of the phrases—which is also happening in China.

TY: So is it a deliberate mis/re-interpretation?

GG: Yes. When I created these works, I was picturing “gutter oil” being hung in a Chinese billionaire’s dining room, “flies” in his luxurious bedroom and “tigers” in the sitting room. That’s the amazing thing about being an artist. You can make meanings out of something that normal people don’t realize. You can make “gutter oil” look beautiful so that those rich people can gaze at it while enjoying their delicate, expensive meals.

TY: Did you customize the pieces for this show? Contextualized them for Hong Kong?

GG: Yes the phrase works were made for this exhibition. But this show wouldn’t have problems being shown in Shanghai either as it’s not politically sensitive at all. These words are all over the internet; they’re also relevant to Hong Kong. For example, the phrase “zhongguo dama” (Chinese middle-aged woman) was coined in Hong Kong when they rushed over [the border to Hong Kong] to buy enormous amounts of gold when the price fell last year. I want Hong Kong people to think about this.

Earlier this year, I saw Hong Kong people protesting in front of a Louis Vuitton shop and shouting at Mainland Chinese shoppers. I was thinking, “Come on, Hong Kong people, grow up!” I mean, you have to accept change. All these Chinese middle-aged women don’t spend that money in Mainland China; instead, they brought it to Hong Kong to boost the economy. I think there is one thing Hong Kong people must learn: You have to accept change. It’s hard—but it’s hard everywhere. In the UK, many immigrants are coming in, but they are also contributing to society.

TY: Are you going to create more works related to China?

GG: It depends, but I do wish to have a solo exhibition like this in mainland China one day. Even better, in Lhasa.

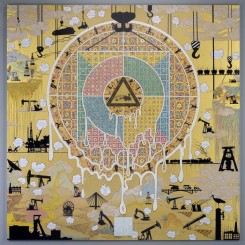

Gonkar Gyatso, “Tiger”, mixed media collage, pencil, paper, aluminium and plexi on dibond, 51 x 51 cm,2014