Earlier this year, in June, Shanghai’s Rockbund Art Museum and HUGO BOSS announced the creation of the HUGO BOSS ASIA ART, with the inaugural award focusing on emerging artists from Mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau. Conceived as a biennial award, with plans to focus on other regions of Asia in the future, this first edition includes an exhibition of the seven finalist artists, a series of lectures, dialogues and a symposium as a part of the educational program. The jury, made up of prominent curators, artists, and writers, among others, will determine the prize winner, who will receive a stipend of 300,000 RMB, on October 31.

The exhibition of the finalist artists—Birdhead, Hsu Chia Wei, Hu Xiangqian, Kwan Sheung Chi, Lee Kit, Li Liao, Li Wei—will open on Thursday, September 12, 2013, at the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai.

Larys Frogier, the director of Rockbund Art Museum, took the time to answer some questions about the concept and scope of the award.

(Disclosure: according to our Ethics Policy, I am obliged to disclose that I have been translating texts for the Rockbund Art Museum).

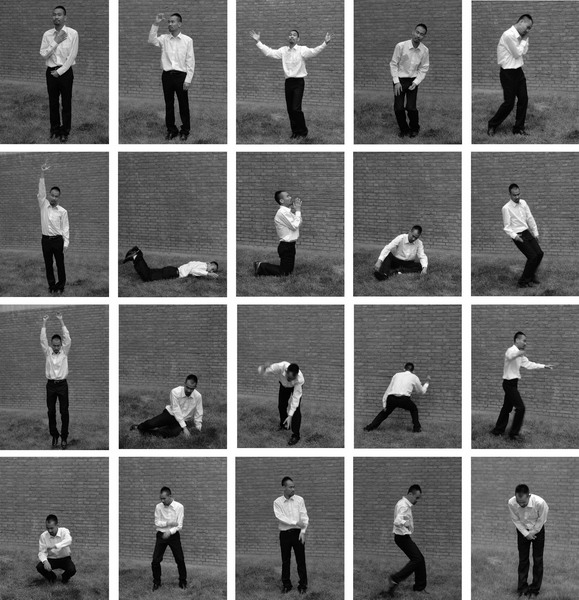

Hu Xiangqian, “Xiangqian ‘Art Museum (Beijing)’”, performance, video, 14’15”, 2010

胡向前,《向前美术馆(北京)》,行为录像,14’31”,2010

Daniel Ho: First off, I’m sure that on everyone’s mind is “another art prize.” Is there something in the “ecology of art” in China, so to speak, that makes art prizes interesting and fruitful — for instance, in the determination of value at a remove from the market? Do you think art prizes occupy a different position with respect to cultural legitimacy here in China vis-à-vis Europe or America? Or will they?

Larys Frogier: Art prizes in any global country contribute to the support, discovery and legitimation of artworks and artists. In Europe and America, you have numerous art prizes with this specific aim of strengthening and supporting both the prospective and the academic sides of art (the Marcel Duchamp Prize in Paris, the Turner Prize in London and the Hugo Boss Prize at the Guggenheim in New York…). These prizes have inevitable effects on the art market, since they highlight artists to be acclaimed and collected by private and public organizations.

The majority of art awards in China find their specificity in the way that they are more exclusively connected to luxury brands and are pursuing another kind of legitimacy: the use of art to legitimate in a straightforward way the brand and its own market in the Chinese economy. Sometimes, this aim has bad effects like intrusion of brands into museums to show their products, or the marketing instrumentalization of artworks to illustrate and promote a product.

Some people believe that this is really a new way of extending artists’ creations towards stronger distribution and visibility, whatever the means could be. But I personally would rather ask the question: how are the luxury brands coming into China able to generate strong creativity by demonstrating their full support of independent artists and creative art museums, taking a risk on artistic values rather than confirming the existing market?

How could they support the artists to allow them to attain a passionate and critical position, looking for a sustainable benefit for the art communities but also for the reinvention of the brand itself in their marketing process?

HUGO BOSS’s long-lasting and strong credibility in the art scene originates from the fact that HUGO BOSS is not involved in any part of the curatorial process of a project. The success of their support comes from the way they build confidence in partners who are really involved in artistic values and curatorial practices.

HUGO BOSS has decided to partner with the Rockbund Art Museum due to the high standard of its curatorial practice, independent thinking and recognition in the art world.

HUGO BOSS ASIA ART has a special focus on contemporary art in Asia to think, invent and represent changes in Asia in the era of post-globalization. Secondly, it intends to combine an art award, curatorial practice and a continuous theoretical research platform for inventive and collaborative projects. Thirdly, the award originates from an institution — the Rockbund Art Museum — which is fully engaged in what is unfolding in the Chinese art scene.

DH: Someone remarked to me that she found it strange to have a Hugo Boss Asia prize but not a Hugo Boss Europe prize. I suppose that what she found odd is to have “Asia” as a particular category. What do you say to that? Perhaps a bit more philosophically/theoretically, how does this play into the relation of universalism/particularism?

LF: This important question is related to a blatant historical construction: until now, even though post-colonial theories and curatorial practices are changing the scene, it is a fact that contemporary art and its history were and are still built from a Western perspective as a “universal” one. Your friend knows very well that universalism is sometimes a system and an ideology which inevitably builds references to exclude some or to categorize, name and stereotypes others.

The HUGO BOSS ASIA ART concept confronts exactly this critical analysis: we consider Asia as a construction and as a question to investigate rather than a monolithic area of fixed identities.

Having said that, let me also emphasize that I don’t want to reduce the vision of Western art history to universalism, since it is such a very complex, dense and rich context based on decades and decades of migration in Europe, from the Middle East and to the Americas for example. Historians are just discovering today how this Western art history is not so exclusively “Western”….

Lee Kit, “How to Set Up an Apartment for Johnny”, Hand-painted cloth, cardboard paintings, video and ready-made objects, 350 square feet, 2011

李杰,《如何为乔尼设置房间》,手绘布,卡纸画,行为录像和现成物,350平方,2011

DH: How do you define “Chinese” in the “Best Emerging Chinese Artist” category? What does “originating” mean? Or shall I say: Can someone not of Chinese descent but who was born in HK (for example) be eligible for the prize?

LF: Yes an artist born in Hong Kong can be eligible for the prize.

HUGO BOSS ASIA ART is launched in the context of China and inaugurated from the Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai. This local context makes the inaugural edition of HUGO BOSS ASIA ART able to deal with emerging artists from Greater China including Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau. Rockbund Art Museum cannot pretend to embrace Asia Art in “one glance” and it is the purpose to move the prize for each edition.

Kwan Sheung Chi, “Ask the Hong Kong Museum of Art to Borrow ‘Iron Horse’ Barriers: I Want to Collect All of the “Iron Horse” Barriers in Hong Kong Here”, 100 “Iron Horse” barriers, plexiglass mirrors, variable dimensions, 2008

关尚智,《请香港艺术馆帮忙借「铁马」围栏:我想收藏香港所有「铁马」围栏在这儿》,100只「铁马」围栏、塑料玻璃镜,尺寸依场地而定,2008

DH: Aren’t the art worlds of Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan quite separate? Why put them together (of course, there is still the political “reality” of “One China”)?

LF: As you said, there is the political reality. On the opposite side, it is also reductive to say that the art worlds between Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan are simply separate.

When you have a close look at contemporary art in Greater China, you can see how different the practices, aesthetics and social challenges are from one city to another. If you look at the finalist artists, from Birdhead in Shanghai, Li Wei in Beijing and Hsu Chia Wei in Taipei, they do not share the same challenges for shaping memory and contemporaneity. Even from Kwan Sheung Chi, Lee Kit in Hong Kong and Li Liao in Shenzhen or Hu Xiangqian, the appropriation of daily life and the uses of “public” in art are really different.

So, you can feel that these differences are built upon layers and layers of cultural background, connections, frictions and oppositions that really need to be questioned. I don’t think that this first edition of HUGO BOSS ASIA ART encloses Chinese art within a fixed definition, but it rather highlights new visibilities and the strong diversity of contemporary practices in Greater China, which is important for the analysis and a better understanding of art in Asia and internationally.

This is also why we made the choice to have in our first jury members with strong and different curatorial practices contributing to all these open and multi-area challenges. These curatorial practices are decisive in understanding the mutations in what we call Chinese and Asian contemporary art, because they demonstrate that Chinese contemporary art goes beyond any reductive scheme coming from inside China but also from any stereotypical representations coming from the outside.

Li Liao, “Consumption”, performance, ready-made, variable dimensions, 2012

李燎,《消费》,行为 现成物,尺寸依场地而定,2012

DH: In China, quite a few people have been talking about the need for local Chinese to have more of a say in the discourse of art as well as the collection of art (i.e. exhorting/urging local collectors to collect so as to have more influence in the development of Chinese art). How does the Hugo Boss Asia Prize stand in the relation to the international and national/domestic scenes in building processes of “taste” and artistic validation? Or: Can we so easily say that national boundaries don’t matter?

LF: HUGO BOSS ASIA ART aims to support emerging Chinese contemporary artists. Emerging Chinese artists are those who run at the start of their artistic creation and exhibition practices, question, extend and enrich the possibilities of contemporary art. They do not only deconstruct established codes of art, but take the risk of offering unexpected forms, experiences and meanings to the process of making and seeing the picture.

We believe that the on-going progress of contemporary art in Asia in a post-global era depends on our ability to cultivate continuous, inter-penetrable, porous dynamics with respect to otherness.

I have to say I do not believe in this global utopia of “no boundaries”, simply because this globalism is another system, another form of universalism built for the purpose of the economy. And it violently erects other oppressive boundaries — invisible ones different from national boundaries but so exclusive and destructive.

DH: Is there a particular rationale that the prize has to be awarded to one artist? Why can’t it be awarded to one winner along with smaller prizes for the runners-up?

LF: Because it is an award for one winner.

DH: Will the winner have a solo exhibition at the Rockbund Art Museum —like the Hugo Boss Prize with the Guggenheim Museum in New York?

LF: No.

DH: How much of a say does Hugo Boss have in the administration and management of the prize, especially in terms of the future direction of the prize?

LF: The conception and curatorial process of the HUGO BOSS ASIA ART is fully and independently operated by the Rockbund Art Mueum.

The independent art award is organized and administered by the RAM.

Any future direction of the prize will be discussed accordingly between RAM and HUGO BOSS.

Since Rockbund Art Museum and HUGO BOSS ASIA ART take strong interest in artistic creativity as well as theoretical research, two years is considered to be an adequate period, within which practices which are innovative in the formal sense, and at the same time provocative for critical analysis in the Asian Art scene, can be observed and defined.

The cooperation between Rockbund Art Museum and HUGO BOSS ASIA ART is set as long-term collaboration.