“Itching All Over”: the four characters are inscribed in black ink on the cover of a booklet containing Tang Dixin’s works to date. The simple, smart design comprises the title and picture, finished off with a decorative red thread. Scratching “an itch”, such as a bump from a mosquito bite, can bring about a pleasant sensation, tempting one to scratch it more forcefully; but if the scratching is overdone, the skin will be broken, and the affected area runs the risk of infection and even bleeding. When the wound hardens into a crust and is about to recover, the itching gets most unbearable, but should on no account be scratched. If you can’t resist the temptation, all efforts will be wasted, and you have to start again. Pain is bound to come with the wound, but itching is a necessary healing process after one endures the pain.

These four characters are perhaps the most fitting phrase Tang Dixin has found to describe his creative being or state of being (surviving). Itch is either a desire inside one’s body that is eager to be released but probably will never be satisfied, or an individual’s reaction towards circumstances imposed by the external environment. For creative beings, “itching” expresses a vivid, bodily-reaction-inducing state that one is eager to reach, but cannot. Yet the circumstances imposed by the environment tend to have been proactively and subjectively created by the artist. Upon seeing these four characters, readers may wonder whether they feel itchy themselves. Zhuang Dishen writes in the preface of a collection of essays titled Itch (co-edited with Yu Yishuang), “An itch from within is hard to scratch. No matter how painful and lonely you are and how much you want to dispel it, the spot deep inside that is hard to reach remains itchy.…The itch is the anxiety of our time, and an underpinning of the psyche of our time….” This reminds me of something said by the Master in Samurai X: Trust and Betrayal, “Our time and the public psyche are both troubled. In a volatile time, even powerful forces can’t stem the tides of time.”

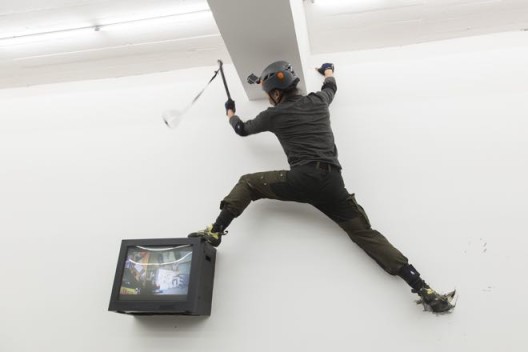

A sense of thrust by exerting one’s full strength, followed by physical depletion, runs through Tang Dixin’s performance art. His solo exhibition “Mr. Hungry” at AIKE‐DELLARCO in Shanghai is composed of a performance art piece at the opening ceremony, as well as the traces left behind and video installations. The series of videos record Tang Dixin’s climbing in interior spaces in which he “intentionally avoids any conventional route” (to quote the press release of “Mr. Hungry”); fridges, cabinets, air-conditioners and sofas—which surround him in the living space—are used as landing and supporting points for climbing.

Now reflect on “intentionally avoids any conventional route” for a moment. Have you had the experience of getting lost in today’s shopping malls? Or looked for a restroom or subway station amid a myriad of shops and packaging? To find a specific shop would be even harder. A shop is a special example. Unlike a riverside green belt with sidewalks or a giant supermarket with escalators winding up and down, a shop has a designated route buried in a dazzling maze. The purpose of this maze seems precisely to conceal the entrance. Tang Dixin climbs around the interior space, but not to find an exit or reach a specific destination; his purposelessness intends to remind us of the absurdity and futility of our routine courses of action and trajectories.

The videos are recorded with an overhead camera worn on Tang’s head, capturing the original recording of his climb with little editing. The view through this first-person perspective has a strong sense of motion due to constant movement. While watching these videos, viewers can perhaps easily insert themselves into the trajectory of the climb. Light but audible breathing conveys not the type of eager anticipation or readiness exuded by felines seeking out their prey, but rather a relaxed, playful mood. The posture of moving with both hands and feet does not interfere with walking. While its support of our body weight enables us to walk upright, our spinal cord needs to be extended regularly; many stretching exercises extend or curl the spinal cord while we are in a crawling position. Through crawling and recording with first-person perspective, Tang Dixin seems to have found a trajectory to rediscover indoor spaces, while this trajectory is also used in his opening performance piece. Nevertheless, such recording with a first-person perspective appears to have greater significance for the process of behavior itself than as the object being seen.

Tang Dixin, sporting a pair of skis and holding ice picks, climbs up the wall, swaying, while holding onto a red wooden door. The blades at the front of the skis needed to be forcefully inserted into the concrete wall with wood frames; but getting the blades out of the walls where they were stuck wasn’t as easy as extracting them from ice would be, and required significantly more strength than inserting them. Having grown up in the mountains of Fuyang, Hangzhou, Tang Dixin is adroit at climbing hills, trees and bamboo, but never received any training in rock climbing. He only tried it out once on a wall before the performance. Therefore, he was uncertain about how the actual performance would turn out. It is precisely such an uninsured, unpredictable, raw circumstance that injects intense anxiety about danger into the mind of the viewers. There is a mix of anxiety and excitement in the viewers’ attentive gazes, and the performance artist undertaking persistent yet arduous climbing that a heightened tension revolving around the dichotomy between seeing and being seen was formed.

Tang Dixin wore the camera throughout. Nevertheless, as he was primarily facing the walls and moving horizontally, what the camera captured was almost invariably white walls along with the anxious, nervous faces of onsite viewers recorded when the artist occasionally lowered his head to look at them. Tang Dixin intentionally climbed up to the ceiling, forcing them to look up as he moved atop the four-meter-tall walls. The television sets mounted on the walls became the support for the artist’s occasional rests. His thigh muscles (propelling the skis) drew grey arcs on the walls with gradually-decreasing vitality. The attacks from the ski blades and ice picks left lines of bruises on the walls. One ski fell off, followed by an ice pick. Tang Dixin then threw off all the equipment and climbed with his bare hands. The performance art piece, lasting for half an hour, concluded with the artist jumping down successfully at the entrance of the gallery.

Even without any prior knowledge of the opening performance, viewers who stepped into the gallery were still startled—one can tell from their gazing upon the brutal traces of wounds on the walls. The unmistakable occurrence of “someone having climbed the walls” can be reenacted endlessly in viewers’ imaginations. It can be said that spaces, post-human-behavior, effectively retain and manifest the tension present at the moment of the performance.

Climbing walls inevitably reminds one of the ongoing “Drawing Restraint” series started by Matthew Barney in 1987, in which “restraints are employed as a condition for development as well as an instrument for creativity”, and scenes of performance art practice featuring artists tied to bungee cords, forcefully twisting and climbing while drawing on the walls—several of these recorded the process in videos which in turn became artistic works. The differences between actions, performances and art works in Tang Dixin’s practice, however, are rather murky—or, they can be seen as aiming to compose a fully integrated whole. Barney’s work is a direct expression of how restraints relate to creation; Tang, however, has never regarded his performance in terms of restraint, as there is no object of restraint—if it has to be identified, this will depend more or less on the artist himself.

Those who are familiar with Tang Dixin’s art works may still take delight in talking about the incident of him lying on the subway tracks. That incident, in 2010, was entitled “Act of God.” Looking up at the climbing Tang Dixin while standing in the gallery space may invoke quite a different state of mind than watching on Youku a self-recorded segment of him lying on the subway tracks. I wonder if both states of mind contain a certain indescribable sense of admiration—indescribable because few onlookers are able or dare to jump onto the stage to perform (although such a phenomenon is becoming more commonplace nowadays, and is even encouraged). Tang Dixin has never denied that his performances are staged for others to see, and that he hopes those who see him perform will have some response—be it a quiet, slight change of facial expression or verbose feedback. That’s not for the visibility of response, but for a sense of sympathy and compassion after throwing something to the sky. Before making the “Act of God” incident happen, Tang Dixin conducted thorough investigations, visiting many subway stations in Shanghai and assessing the duration for which trains stop at each station, before eventually selecting a platform of “guaranteed” security. He was by no means planning his own “accidental” death, or aiming to make himself an “internet celebrity”; rather, he was staging a performance art piece. Following the incident, the police detained Tang Dixin for ten days before releasing him. For him to jump resolutely down onto the tracks and lie there enduring the enormous pressure, speed and the sound of the train braking, and then jump back onto the platform—amid all his determination, what crossed his mind? It was action: survival!

Such “extreme” behavior is highly susceptible to moral judgment. Take Tang’s performance “Fly” in 2009 as an example. Tang Dixin and several other young people jumped off a second story patio (with friends catching them in blankets below); this drew the disapproval of an older female resident nearby. The lady tried loudly to dissuade Tang Dixin and his group from “wasting their lives in their prime of youth.” Unlike others who jumped in an almost upright position, Tang Dixin’s pose closely resembled that of Yves Klein in his performance “Le Saut dans le Vide” on Rue Gentil-Bernar in the Fontenay-aux-Roses neighborhood of France in October 1960—jumping off a building like a bird spreading its wings and with his head high as if he were flying. With gravity being impossible to escape, Tang reportedly suffered hand and elbow fractures; but he jumped twice nevertheless. This performance piece was replayed in the program “Retrospective” curated by Biljana Ciric in 2010, in which Tang Dixin fell to the ground in an upright position multiple times. When he invited onsite viewers to get onto the stage and interact with him, a girl came up to him and shoved him to the ground with one powerful thrust. He later recalled, “I was psychologically prepared for the preceding falls, with a conscious intention to control my body; but to be pushed down like that was totally unexpected, so I tried to protect myself with my hand, reflexively. Apparently, I couldn’t really fully control that. I was somewhat disoriented at the time of the fall, thinking I was able to stand up, but my legs failed me. Eventually, I managed to stand up only after several attempts.”

The above-mentioned performance art pieces are apparently all scenarios of “personally testing the limit of risks,” with Tang Dixin placing his body in dangerous circumstances. As someone acting out his artistic vision, his courage and behavior, personally testing the limits of danger while seemingly automatically separating out his viewers, can also be taken as an encouraging call or beckoning. It’s a beckoning not to imitation, but for a customary alert towards the point of departure for such dangerous activities. “In the performance art piece “I will be back Soon” in 2008, the viewers were asked to throw soaked toilet paper against any random surface, such as the walls, ceiling, beams and floor, and I was then to retrieve the toilet paper as fast as possible, through different means, but only with instruments available on site. Different viewers posed different levels of difficulty for me, and the performance lasted for about two hours.”

The images of self-abuse created by performance artists have a way of seeping deep into our consciousness. From Zhang Huan’s early performance piece “12 Square Meters” (in 1994, seated in a public latrine covered in fish sauce and honey which attracted flies to crawl all over his body, lasting for one hour) to He Yunchang’s performance piece “One Rib” (in 2008, having one rib removed by accepting a medically-unnecessary operation), the tension between individuals and society is alluded to more or less through the artists’ endurance of pain (and various discomforts) and the exploration of their limits in enduring pain while employing their bodies as the medium. However, Tang Dixin’s original intention is not a similar attempt to “test his own limits of endurance”, but instead to combine his individual practice with public motivation; this is most evident in his performance works.

With viewers’ participation in mind, Tang Dixin broadened his invitation to them. In his work “Rest is the Best Way of Revolution, 2012-2013”, where walls were inscribed with fonts emblematic of the 1980s and painted in red and green, Tang Dixin, in a doctor’s white gown, dressed the most used body parts of individual viewers in order to let them “rest up”. When they left, almost all of the viewers were wearing white plaster casts. This was a response to seemingly endless human rush and bustle with a posture of rest and non-action. This approach of dressing “the wound” is obviously a lot more genteel than that of Zhao Zhao, who used a knife to stab Sun Yuan, a volunteer he recruited. This “big character poster” type of aesthetics was also used for Tang’s performance piece “I Must See a Rainy Day Today” (2012). In contrast with “Rain Room” by Random International, Tang Dixin’s self-made backpack showerhead allowed him to be rained on constantly on the day of performance. With both hands in his trouser pockets, he closed his eyes, readily receiving the water flowing down his body, and showing no sign of obstruction to his breathing. The audience was prompted to grin with amusement, only to realize that while smiling, they were also experiencing a vague itch which they couldn’t scratch.

This may not be an appropriate metaphor: but if Tang Dixin’s performance art works are stars, then his paintings would represent a vacuum, or perhaps a sense of time, which might be more fitting. His paintings more often than not have a grey-blue tone. He has said that often, if a painting doesn’t turn out well, he will scratch it out and repaint it so that there may be another painting beneath each painting. This grey-blue hue corresponds with his typical facial expression—a casual smile lurking at the corners of his mouth, yet with a certain quiet sorrow in his eyes. Derek Jarman writes in his Blue,

You say to the boy open your eyes

When he opens his eyes and sees the light

You make him cry out. Saying

O Blue come forth

O Blue arise

O Blue ascend

O Blue come in…

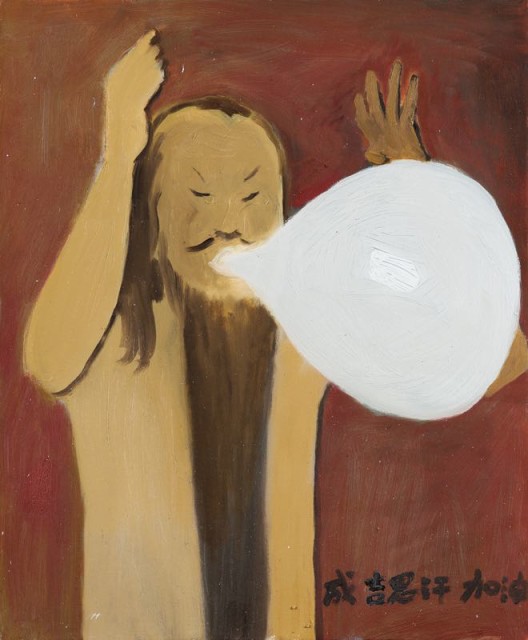

The smoke, clouds, fog and water often appearing in the paintings bear solid weight. In cityscapes (buildings, streets, lamps), clothed or unclothed human portraits, body parts, animals, or cartoonish scenes featuring items like a cigarette-butt-clutching fire extinguisher, and even such “evil paintings” as “Come on Genghis Khan” (2013), vague surrealist imaginations and intentional manifestation of the reality behind them permeate. As a young man from the countryside now living in the city, frequent returns to his village ignite many childhood memories about a much-changed place, as well as sentiments towards the village that well up in his acceptance of transformation. The appeal of the countryside stems from its rustic charm, its tall mountains, its streams and trees, its rugged terrain and indomitable fortitude and sweet-smelling chickens that are free to stroll around. The urban space is created for human beings, yet it loses humanity’s authentic dimension; besides, it gradually erects habitual tall walls, blocking the scenery and paths through. This sense of isolation is perhaps an alternative composition of that sorrow detected in the paintings. The definition of reality itself, since the outset of modernism, has undergone countless changes. The more blurry the boundary between perception and reality becomes, the more easily this blurriness can be incorporated into reality.

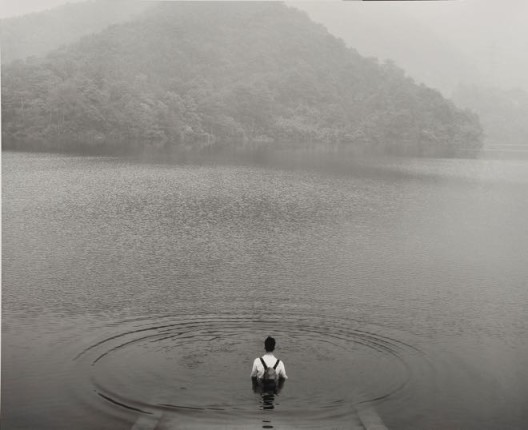

These paintings, along with these performance art works, are all by Tang Dixin; they all possess a certain tension stemming from calmness, as well as a certain gentleness born from loneliness. Paintings and performance art appear to exist in parallel, without overlap. But there do exist such paintings as “On the lake”(2013), which originates from his own performance work “Floating”(2009). Tang Dixin is lying in a bathtub floating at the center of a lake. The work is entitled “Crooked Times” (2014) as the bathtub, the tree, man automobile, and shadow are slanted. The setting sun appears to be burning the sky red; as the shadows darken, the power of the sun recedes, exhibiting anomalous gravity. Should he fall in that painting, he would not fall onto a “ground”.

Born in Hangzhou in 1982, Tang Dixin graduated from the Department of Oil Painting at the Academy of Fine Arts at Shanghai Normal University. He lives and works in Shanghai.