As always, galleries and institutions large and small have begun drumming up noise about their first show for the year of the dragon with artists, critics, curators along with art galleries, dealers, media all joining the fanfare. But perhaps all this noise is not necessary at all. As the line in the film And the Spring Comes Goes, “Spring came but in the city there were scarcely any traces of Spring, though the wind had changed. I always felt something was about to happen, but when Spring came nothing did.” What a new year really brings for us, the reflections it allows us, or what new trends which will emerge in art — these are not really the topics in question. After all, the avant-garde will still be the avant-garde, whatever needs to be critiqued will be critiqued, and whatever is to be subverted will also be subverted. In this season of rebirth, instead of rushing to “predict” formulaically the trends in this year’s contemporary art, perhaps it is more worthwhile to think of what was thoughtful and meaningful in the past year.

Admittedly, a vastness of scale and a sense of overwhelmingness is something always pursued by artists. If we can still vaguely remember (or alternatively maybe we were obsessed with it) Zhang Huan’s “Hope Tunnel” at UCCA (July 17–October 24, 2010) which presented the pain and suffering of others amid the remnants of a train wreck, then this same story of trains is again retold by Huang Yongping in the group exhibition, “Training the Milky Way” at Tang Contemporary Art (March 26–April 5, 2011). Meanwhile, Zhang Huan seems to be constantly challenging himself. After relocating an ancestral temple to the Shanghai Art Museum for the 2010 Shanghai Biennale, last year he staged “Zhang Huan: Q Confucius” (October 15, 2011–January 29, 2012) at the Rockbund Art Museum. It is absolutely superfluous to offer up interpretations of the meanings of these installations/sculptures, because their meanings cannot be more obvious; it is their monumental scale which truly stuns viewers and forces them to step back. Of course, all such works pale in the face of Ai Weiwei’s 100 million sunflower seeds — whether in terms of shock, complexity of production, the profound visual effect and the stunning impact of scale.

Zhang Jiebai, “Techno-gym,” oil on canvas, 60 x 40 cm, 2011.

张洁白,《Techno-Gym》, 油画, 60 x 40 cm, 2011(Boers-Li画廊)。

But at any rate, these big moves are without a doubt the art games played by a minority of artists. These “interactions” between “the audience and the works” inevitably mentioned in press releases do not truly exist, since within these “interactions” between the audience and the artists, there is no equal and democratic relationship. What the audience gets is nothing other than the shock and awe that they cannot find in everyday life. In contrast, the past year has seen a number of small events and exhibitions, which could not and did not try to win over the public or the participants but instead strove to allow people to reflect and bring up various associations to concrete problems. Of course, their influence is often limited to a specific area and field.

Zhang Jiebai, “Snake Game,” oil on canvas, 70 x 70 cm, 2011 (Boers-Li Gallery).

张洁白,《Snake Game》(Boers-Li画廊)。

It must have been around this time last year that Xiao Ge, sister of Xiao Lu the artist, helped organize the second installment of the “China Contemporary Art Golden Palm and Razzie Awards.” It was really just a little stunt: the big names didn’t seem to care much about what prizes they had won, and several were so “busy” with their work that they did not bother to show up. Yet this mounted a challenge, as yet feeble, to the authorities within certain fields of art. Thus, the award ceremony created a stage for a series of “small” positions or stances last year.

Among them, the “Little Movement” project (OCT, Sep 10–Nov 10, 2011), initiated by the artist-critic-curator couple, Liu Ding and Lu Yinghua, was perhaps the most influential small movement last year. Even though like practically all art events or exhibitions these days, we get more conceptual than substantial content in the curatorial statements, still, we can simply understand it as a series of individual works which are small, blurry and micro in scale. As the curator admitted: “the influence of the “little movements” is more like a “slow influence” rather than for short term returns and strategic goals which are simplified in general discussions.” The ambiguity of such position evokes the “soft realism” of recent years.

This “small position” contains several different aspects. At the most basic level, it refers to the artist’s age and experience. For instance, the “51m2″ project at Taikang Space, which featured 16 emerging artists (Mar 19–Apr 16, 2011) from the same project the year before, constituted a retrospective project to encourage young artists and then there was “CHRISTMAS义乌(EVE) — A Carnival of Tiny Things in 2012.” In addition, the use of narrow space was also a consideration of some artists, as with He An’s exhibition “Wind Light as a Thief” (Jul–Aug 2011) at the Arrow Factory in one of the Beijing hutongs, or the exhibition “A Mole on Each Breast and Another on the Shoulder” (Jul 28–Aug 21, 2011) at Magician Space. The latter, which demanded that the audience squeeze through the narrow space between two walls inlaid with rubber buttons, left a deep impression on the public’s sense of touch.

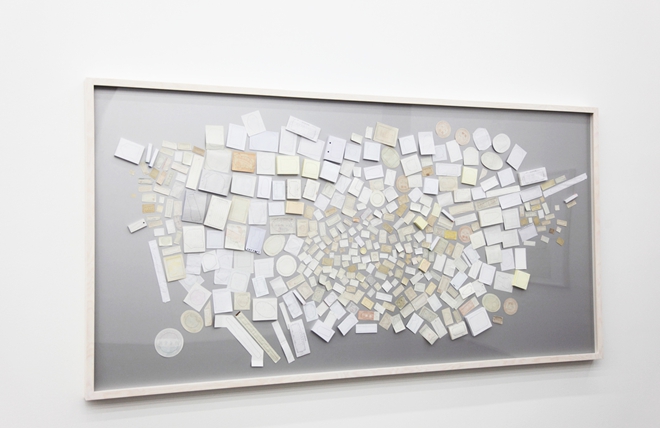

Song Dong, “Wisdom of the Poor (2005-2011)”, installation, 392 x 245 x 365 cm.

宋冬, 《穷人的智慧 (2005-2011)》, 装置, 392 x 245 x 365 cm。

Of course, the enlargement and reversal of everyday items in order to create an effect of defamiliarization as well as the folksy and regional utilization of resources have always been “eternal themes” in contemporary art — it is just that last year this trend became more pronounced. Examples include Song Dong’s UCCA exhibition “Wisdom of the Poor” (Jul 16–Sep 8, 2011), and Song’s show at Chambers Fine Art “The Way of Chopsticks” (Jun 11–Jul 30, 2011) in collaboration with his wife Yin Xiuzhen. Then there was “Cell” by Qiu Zhijie at Pace Beijing (Jul 17–Sep 3, 2011), and Hong Hao’s show “As It Is” (Nov 26, 2011–Feb 26, 2012) at Beijing Commune.

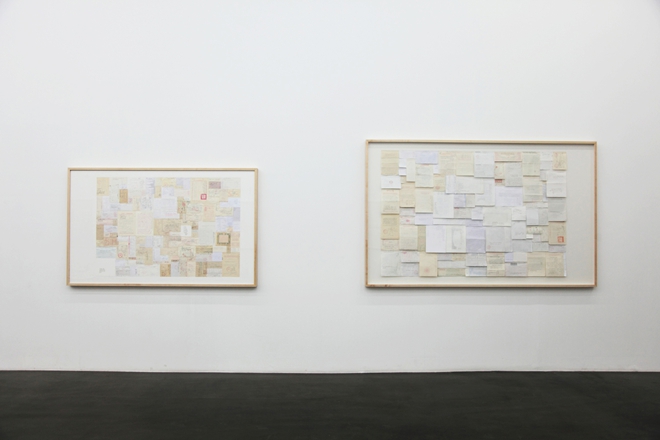

In the ever coming and ever passing era of Weibo (China’s answer to twitter), the qualities of being succinct, temporary and ephemeral found an echo in the art world. “30-day Bookstore” by “Brother Walnut” held in Shenzhen is such a project with a strong feeling of the underground and kind of literary form of expression. (This year, they launched a new project, “1 Square Meter of Land”). However, the influence of these projects was accordingly weak, not even comparable to some group exhibitions at more established institutions, such as the group exhibition “Crosshairs — An Exhibition of Small-Scale Easel Works on Easel” (Sep 17, 2011– Oct 16, 2011) at Iberia Art Center, Lin Jingjing’s “Public Privacy” (White Space, Jun 11–Jul 5, 2011), Yuan Yuan’s “New Works” (Beijing Commune, Sept 29–Nov 20, 2011), “You Are Not A Gadget” at Pekin Fine Arts (Jan 15–Apr 18, 2011), Zhang Jiebai’s “I’ve Got Something” at Boers-Li gallery (Oct 20–Nov 20, 2011), and the group exhibition “Micro Life” at Soka Art Center (Jun 25–Aug 7, 2011) among others. In these highly personal or feminine exhibitions, they either explored the questions posed by the virtual vs the real, or returned to the small fragments of every day life and “the self.” Of course, they also inevitably touched upon “ideology,” which contemporary artists are all talking about in their own ways.

Huang Yong Ping, “Leviathanation,” fiberglass, stuffed animals, train, 2100 x 300 cm, 2011 (courtesy of Tang Contemporary Art).

黄永砯,《专列》,装置,玻璃钢,动物标本,火车车厢, 470 x 2100 x 340 cm, 2011 (鸣谢: 当代唐人艺术中心)。

In essence, what are these “smallnesses” that appeared last year? The social scientist Michel de Certeau talks about how minor practice is the everyday level of social life, through which the analysis of the essence of social subjects can be possible. The political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott in Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistanceoffers another lens in which to view the situation. In the book he discusses how as a disadvantaged group, peasants, do not use revolution, nor cause tremendous pain for the upper class; instead, their everyday resistance is mounted in the forms of teasing and mockery, little jabs and taunts, secretly undermining their authority— such are the tools of the weak.

Smallness is an attitude, a posture, and a kind of helplessness.