The purpose of a whirlwind museum tour was to explore what China might do with roughly 5,000 new museums built in the past decade. This is a phenomenon marked by a dearth of reliable information. Museums are shrouded in their own publicity, or cling to the reputation of superstar architects who design them. My curiosity lies in the content of these entities, and what actually goes on at a ground level. In a basic sense, where are they and how does one find them? Who built them and what do they look like? Perhaps most importantly, what this all means for a generation of Chinese coming to public art anew, warming to the practice of museum visits and faced with the unusual challenge of cultural resources in over-abundance.

Over twenty days I traveled through six provinces, covering selected institutions in lesser known locations—a mixture of public and private. Included here are surveys in brief of those outside Beijing and Shanghai. Largely, these museums display antique and older art forms, using new buildings to espouse traditional, didactic or state values. The difference between public and private spaces was overwhelming; the public tends to lean on scale and location to persuade visitors of their value, while private museums each adhere to a unique and intimate vision.

SHAANXI

OCAT Xi’an Terminal, Xi’an

Public (Completed: 2013)

Xi’an, China’s Tang Dynasty capital, is cluttered with history. Contemporary offerings are, however, vastly limited, so the OCAT site here (located in an upscale commercial and residential compound) is an important contribution.

Speaking with some of the staff there, there was genuine excitement at being involved in a contemporary arts institution. Even the security guards were eager to assist. The danger with many of these spaces is harnessing the audience: who is this work for, and how are those people brought in through the door? “About Painting”, shown earlier this year, was an exhibition particularly sensitive to questions newcomers may have about this form of working and its relevance today. Li Shurui’s painted installation sweeping over the walls upstairs lifts even structural spaces into the foreground. In the exhibition-mounted video interview, she explains that the environments we live in speak so much of our perspectives and sensibilities.

The gallery has added an activity center (QR codes cover every surface) and a steadily growing reading room—likely the personal collection of the director, the British curator and writer Karen Smith. Their weekend public programs are open for anyone to apply and propose content. This is obviously a valuable opportunity, and it will be interesting to watch the evolution of the space as it seeks a balance between being a guiding resource and open platform.

Elaborate sunken courtyard, adjacent to the Qiujiang Museum of Fine Arts, Westin Hotel Xi’an

曲江美术馆旁精致的下沉庭院,威斯汀酒店

Qujing Museum of Fine Arts, Westin Hotel, Xi’an

Private

Completed: 2012

It’s hard to get past the entry ticket to the Qujiang Museum, which at RMB 380 for a place with only two rooms might be the worst cost to museum size ratio in China. However, if you are a guest of the five star hotel in which it is housed, entry is complimentary.

Inside there is minimal signage for the museum, and only one elevator which descends to ‘Museum’ in B2, below the Spa and restaurants on higher levels.

The two rooms are the temporary and permanent exhibition spaces. Temporary being beautiful Dunhuang mural copies, unfortunately hung in a dank basement with dryboard walls, poor lighting and non-chic piping. The permanent space, however, was like a vaulted jewel box. An extension of Neri and Hu’s hotel edifice, artifacts were displayed in careful clusters within a strongly delineated architectural space. The collection is that of Zhou Tianyou (former Shaanxi History Museum curator) and on show was only a fraction of the total. The famed gold suit of armor and (advertised) 7000 square meters of exhibition space were nowhere to be found. It was, perhaps predictably, devoid of other visitors.

Why would the hotel invest in such a space, apart from providing a guest indulgence, in addition to lavish banquet rooms and a ‘sunken garden’ in a courtyard nearby? Despite a TIME magazine write up, it doesn’t feel like top billing. It seemed unfortunate that while hundreds queued for the Shaanxi History Museum nearby, so few would know about – let alone see – what the Qujiang Museum had to offer.

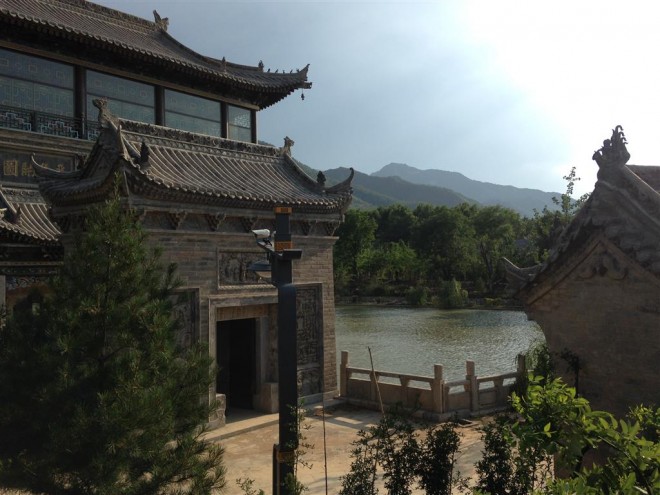

Artificial lake, visible from calligraphy room, Guanzhong Folk Art Museum, Xi’an

从书法室望过去的人工湖景,关中民俗艺术博物馆,南五台山,大西安

Guanzhong Folk Art Museum, South Wutai Mountain, Greater Xi’an

Private

Completed: 2008

An hour South of central Xi’an on the edge of a small village barely serviced by public buses is a sprawling collection of houses and objects to rival any museum in Shaanxi. Founded by local property developer (and party member) Wang Yongchao with the help of government subsidies, this was apparently the first private museum devoted to folk art conservation in China. The objects, which number close to 35, 000, are housed in the physical homes of Shaanxi’s former aristocracy– wealthy families whose residences were all but demolished over years of decline. These houses were salvaged over two decades, forming the bones of the museum and reason for further development of the project. This is as much an open air architectural village as a platform for the folk art antiquities contained inside. The houses line lush miniature boulevards like an incongruous but seamlessly-planned community. Extensions such as private gardens, theaters featuring heritage opera performances and a lake fill out the 30 acres of space. ‘Categories’ of objects occupy entire rooms, including Qing puppets, bronze bells, carved steles, embroidered robes, handmade slippers and locks. They are beautifully displayed and lovingly maintained. The entire complex is serenely devoid of visitors – although this may be linked to its remote location and RMB 120 entrance ticket. It’s hard to know the gauge of success for places like this, which feel like browsing the spoils of an eccentric collector. It is testament, though, to the breadth of private museums unfettered by public constraints.

External source link: http://www.travelchinaguide.com/attraction/shaanxi/xian/folk-art-museum.htm

SICHUAN

Zhi Art Museum, Xinjin Town, Greater Chengdu

Private

Completed: 2014

The celebration of another Kengo Kuma design project in China nearly eclipsed the availability of any further information on this new museum, located at the base of the holy Taoist Laojunshan mountain near Chengdu. Its cascading exterior walls of floating tiles and dark granite make for an image so striking that even without address or phone number, taxi drivers knew it based on picture recognition alone. Nestled within the Alsatian-guarded ‘Belle Epoque’ luxury residential compound, beside an artificial lake and opposite the self titled ‘CEO Hotel’, the Zhi Museum reaches out to a captive audience, rather than a local public one. Its first exhibition, “Architecture for Dogs”, en route from Miami and Tokyo, applies some of Japan’s top architecture and design minds (led by Kenya Hara) to the creation of canine-functional structures. This curious inaugural show considers our relationship to dogs, animals and –more broadly–, our environment. It closes on September 20, 2014, but information on future plans for this museum is very sparse.

Second pavilion, containing mostly Buddha heads, each displayed individually but with acknowledgement of relationship to the others, Luyeyuan Stone Sculpture Museum, Chengdu

二楼摆放的多是互相关联的单个佛像头像,鹿野苑石刻艺术博物馆,新民场镇,郫县,大成都

Luyeyuan Stone Sculpture Museum, Xinmin Town, Pi County, Greater Chengdu

Private

Completed: 2002

‘Luyeyuan’ refers to the deer park in which Buddha preached the path to nirvana towards the end of his life. This is a clue to both the content of the (largely Buddhist) Stone Sculpture museum and the holistic sentiment behind its design.

Located in a county village of Chengdu, it is thoroughly remote and barely signposted. The path into the museum begins in a garden, winds through a bamboo forest with scattered steles, then rises on a soft gradient across a lotus pond into the first exhibition room. Designed by Liu Jiakun Architects, the museum was built in homage to stone masonry, but using rudimentary local techniques and materials.

The result is a perfectly-assimilated structure with outdoor light and sound permeating the museum walls while viewing. Articles are lit naturally, accentuating surface textures. The collection consists entirely of Han and Song stone artifacts from the Silk Road unfolding through the space, with separate pavilions for larger pieces and some on their own in corridors and exterior ledges. Perhaps most astounding is the care with which the objects are presented. The chasm between public and private is stark, the Luyeyuan having a vested interest in the project as only a private enterprise can. It feels correct, somehow, to appreciate the objects with the same degree of reverence with which they are presented. This is communicated at every point – right down to the staff, who kept the museum open an extra hour on a Friday evening to allow a single visitor to browse.

Bronze tree, nearly three meters tall, unearthed at Sanxingdui site, Chengdu

,近三米高的铜树,三星堆博物馆,南兴镇,广汉市,大成都

Sanxingdui Museum, Nanxing town, Guanghan County, Greater Chengdu

Public

Completed: 1997

The museum attached to the Sanxingdui archeological site is a more conservative iteration of the ‘contemporary museum’ in China, but its objects are so extraordinary that it deserves to be mentioned. ‘Sanxingdui’, or ‘three stars mound’, throws a theoretical spanner at historians’ understanding of the spread of culture and civilization within the Yellow river region. This is because the Bronze Age objects discovered here are incongruous –completely unlike anything found before throughout China, and unaccompanied by written records. Gold scepters, foil masks, jade tiger’s teeth and, most incredibly, three meter tall bronze trees, these objects have attracted a following of almost cultish status due to the mysteries surrounding their origin. Manicured, hedge-flanked boulevards lead visitors to two gleaming but low-rise exhibition halls. The prized bronzes have traveled globally, including to the British Museum in 1996 and New York’s Guggenheim in 1998. The museum (partially funded by American Express) was no doubt built to boost tourism in the area, and despite a detached location amid Chengdu’s encroaching sprawl, it was filled with local visitors.

ZHEJIANG

Liangzhu Culture Museum, Liangzhu Town, Greater Hangzhou

Public

Completed: 2007

On the outskirts of Hangzhou, the Liangzhu Culture Museum is part of a monumental new development aiming to rejuvenate a formerly contaminated industrial park. Nestled between the ‘Liangzhu Culture Village’ and the ‘Majestic Mansion’, it is also skirted by a bus depot and a ramshackle village. The museum itself is state commissioned and designed by David Chipperfield architects, of Rockbund Art Museum repute. A beautifully articulated space, it houses an impressive collection of artifacts (some dating back 5,300 years) unearthed in the region from seventy years ago to present day.

Although the entrance requests that visitors “do not lie down”, on a stifling hot Sunday afternoon, the Liangzhu is an air-conditioned oasis for families resting in the main foyer and napping in the café. Exhibition halls are largely empty, but the pieces are stunning. A softly nationalist agenda permeates, with introductions describing China’s greatness and strength throughout history. This is sensationalist time machine meets archeological dig. A ‘4D’ screening room provides “a simulated experience by spraying water, puffing, vibrating and sound effects.”

Maybe this is the way to present antiquities? As a non-ticketed, free entry museum on the edge of second-tier urban sprawl, audiences are largely provincial and local. The ‘café’ and gift shop, constructed from Iranian travertine stone, is a handsome house for a shop selling water guns, candy, mosquito repellant and plastic slippers. The appropriation for local audiences is slightly at odds with the museum’s lofty ideals, but certainly makes sense given the context.

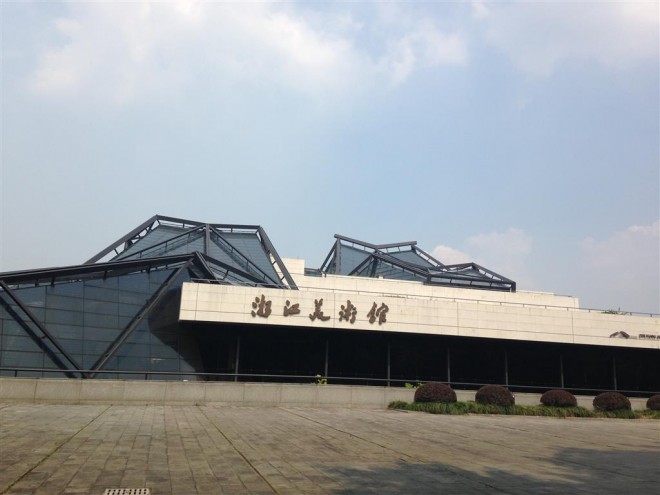

Zhejiang Art Museum, Hangzhou

Public

Completed: 2008

Overlooking Hangzhou’s celebrated West Lake, the Zhejiang Art Museum (not to be confused with the nearby Zhejiang Provincial Museum) is a classic example of a traditional state institution housed in a new building. Superficially, the museum feels lively with diverse offerings. Buzzing with visitors – especially families and children – it has artworks in abundance and a packed public program schedule. However, the programs take only the most basic elements of exhibitions to engage with. Artworks on display, ranging from contemporary sculpture to literati inks, are numerous but lacking in criticism. Lackluster wall labels offer minimal information, and there is a palpable distance between audiences and artworks – neither are really given the chance to respond appropriately. The top floor holds an exhibition of a mid-20th century Chinese-Parisian painter, presented as artistic martyr, tirelessly representing Chinese creativity overseas, and whose (donated) works have finally returned home. The buildings soaring atrium and continuous succession of rooms distracts from the fact that there isn’t much depth of interaction going on.

The dilemma is the same as in many state museums – ‘too much museum’ is surely better than none at all, even if it is still finding its feet. Government driven museums are limited in their programming, having to conform to rules which allow them to offer much of one thing and none of another. Perhaps over time the measure by which museum and audiences mutually benefit will be revised, creating some space for more genuine exchange.

Clean, crisp lines of the entrance courtyard created by I.M.Pei’s architectural vision for the Suzhou Art Museum

贝聿铭为苏州美术馆所设计的线条干净利落的入口处庭院

JIANGSU

Suzhou Art Museum, Suzhou

Public

Completed: 2006

China’s architectural godfather I.M. Pei accepted the challenge to design the Suzhou museum at the age of 85, in part because of a deep respect for the cultural traditions of his ancestral home region, and a desire to communicate that to China’s youth. Anything he touches holds a particular gravitas, true of these stucco pavilions set off Suzhou’s trinket-filled main street. Avoiding the tendency for public art institutions to grow to unnecessary magnitude, the building is a subtle extension of a Qing-era residence with UNESCO protected gardens. Unfolding around a central lily pond, visitors enter through a courtyard then into a main foyer, filtering through rooms just big enough for large families to congregate in. The objects themselves are antiquities, and feel more exquisite than those found in some of the larger public museums. Each space contains no more than about twenty items. The proportions of the whole complex are intimate, like that of a private home, which is difficult to maintain considering sheer visitor numbers. Bilingual materials are available detailing categories of objects, as well as the architecture and current programs. One wing has been reserved for contemporary projects which respond to works in the museum. This space is rotating and curated, with the first project carried out by Cai Guo-Qiang, Xu Bing and Zhao Wuji in 2006.

Inside the entrance atrium, with Deng Xiaoping waxwork flanked by a Giraffe, Shenzhen Museum

位于中庭的邓小平蜡像和长颈鹿,深圳博物馆,深圳

GUANGDONG

Shenzhen Museum, Shenzhen

Public

Completed: 2008

Shenzhen Museum is ideal for anyone seeking a representative flagship museum. Here, the identity of the city is paramount, with other functions (objects and programming) being secondary. The museum is an extension of a new development with government and legal offices, which is so colossal that it covers an entire city block. With free entry and an unusual ‘bags, no bags, pregnant women’ division of crowds, the queues snake along outside. Inside, an airport-like atrium features a modest Deng Xiaoping waxwork, gazing out over a roped off glass floor map of the Shenzhen new economic zone, flanked by a giraffe and an elephant (courtesy of the nature exhibits). Families crush against the barriers to take photos of or with the diminutive Deng. Shenzhen, often spoken about as ‘a city born thirty years ago’, has much to communicate to visitors about its ancient roots and strategic location. On the second floor, the vast Neolithic section tells the story of Shenzhen’s heroic early ancestors through heavy fiberglass reliefs. Key regional events from the past hundred years are reconstructed and brought swiftly under the wing of a distinctly nationalist agenda. In fact, the museum describes itself openly as carrying out “patriotic education wholeheartedly”. Despite heaving crowds, some of the exhibitions were excellent – including one on Tang dynasty female sculptures. Visitors seemed more preoccupied with photo opportunities than absorbing the content, one group of young girls bottlenecking visitors by mimicking the poses of each Tang lady statuette. Ticket holders understandably want to record their visit and share it, but many seemed to be allowing their camera to do the work, taking only the ‘pose and move on’ approach.

Hexiangning Art Museum, Shenzhen

Public

Completed: 1997

This museum takes on an interesting responsibility in the region, having opened in 1997 – the same year as the Hong Kong handover back to mainland China. The museum runs two close, but not directly linked agendas. The first is Shenzhen’s key vicinity to Hong Kong and the straits regions, just as He Xiangning herself (the museum’s adopted figurehead), a painter & scholar who operated fluidly between the national and communist regimes. Secondly, with these regions now providing a much greater public resource post-handover, the museum has deftly appointed a string of capable curators, including Feng Boyi, Hou Hanru and Pi Li to lead their contemporary section. These exhibitions act as an extension of the institution, and hold significant value. Shows such as “Local Futures” in 2013 and “Conforming to Vicinity: A Cross-strait Four-region Artistic Exchange Project” this year tackled pertinent issues of regional identity, consolidation, the Chinese diaspora and urban development.

Shenzhen OCT Contemporary Art Terminal, located within converted former factories, in the sprawling ‘Overseas Chinese Town’ development

坐落在华侨城改造的工厂之间的OCT当代艺术中心(OCAT)

OCT Contemporary Art Terminal (OCAT), Shenzhen

Public

Completed: 2004

A substantial degree of confusion surrounds the OCAT (OCT Contemporary Art Terminal) in Shenzhen, due in part to clunky naming and the enormous ‘OCT – Overseas Chinese Town’ development in Shenzhen’s Futian district where it is located. The OCT area is split across a major boulevard and houses a hospital, schools, a Walmart, a theme park and a Hospitality Training University, among other things. The rise of the mixed use development has marked much of China’s urban change, as has the ‘factory district turned arts hub’ formula. OCAT uses decommissioned 1980s furniture factories, and fanning out from it is the OCT Loft area, containing numerous small galleries, art spaces, cafés and residencies. Clusters like this provide important platforms for art communities; however, they are nearly impossible to navigate in a specific sense. There is more idle wandering and general appreciation than dedicated engagement, which is problematic. The risk, also, is that ‘culture’ is diluted, merely absorbed into a location or district. A kiosk owner next to it had “never heard of the art museum”, while another man replied that it was “all around” without a hint or irony. OCAT Terminal does in fact take the lead, hosting major exhibitions, such as the Shenzhen Sculpture Biennale, now in its eighth year. It also works under the auspices of the He Xiangning Art Museum across the road, extending the contemporary practice and reach of China’s second state-run, modern art museum.

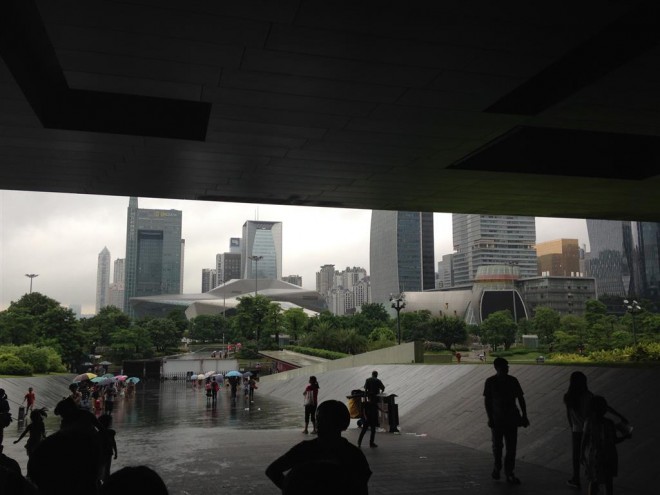

View from the Guangdong Museum entrance, with Zaha Hadid’s “double pebble” opera house and the Children’s Palace visible in Zhujiang new town, Guangzhou

广东省博物馆入口,广州

Guangdong Museum, Guangzhou

Public

Completed: 2010

The Guangdong Museum attracted much attention upon its opening in 2010, and draws close to 10,000 visitors daily. These numbers indicate the readiness for southern China’s public to lay claim to their own institution, without the difficulty of traveling across the border to Hong Kong. Dominating one corner of Guangzhou’s substantial Zhujiang new town development, it is part of urban rejuvenation efforts ahead of the 2010 Asian Games, which in turn brought ready-made crowds of visitors for these new cultural enterprises.

Designed by Hong Kong’s Rocco Design Architects, the museum was created to be a beacon of art and history in the region. Inside, the disconnection between content and building is palpable – it feels like a treasure box built prior to knowledge of its treasure. The permanent collection items are displayed on rotation, and corners of the museum are devoted to natural history, Chinese medicine and wood carving. Heavyweight museum ‘genres’ are represented, but collectively, the museum lacks vision. Traveling shows such as ‘The Etruscans’, and ‘Tribal Art of North America’ were special but dry, with audiences drifting from object to object. This is not to overlook Guangdong Museum’s efforts to connect with global curators and ideas. They hosted the world’s first International Asian Art Curator forum in 2013. It does appear to be difficult, though, for new museums in China to eschew conventional, even conservative modes of presentation. This may need to be revised if new generations of hyper-stimulated, media-savvy visitors are expected to be inspired by museum offerings.