This piece is included in Ran Dian’s print magazine, issue 2 (Winter 2015–2016)

Most art is fragile and some should be placed and never moved again.

—Donald Judd in the first Chinati Foundation catalogue, 1987

The conservation of artworks is not something one hears about much from the media or the people in the contemporary art world. Conservation is unsexy, perhaps—the back-office of an overbearing art market where many of its faults must be dealt with and pieces literally picked up; it is complicated, chemical, and uncertain, and requires an incredibly long-term view: will people in, say, two hundred years’ time be able to look on this work as it was when it was made? It is a discipline as much philosophi cal as physical. Transcending scratches, seepage, fingerprints, and warp, the essence of the work of art is required to be maintained as far as possible. This “true nature” of an artistic object, as Glenn Wharton explained in “The Chal lenges of Conserving Contemporary Art”, concerns the integrity of both the artist’s intent and the work’s original appearance (the two are distinct, but not separate). Debora Hess Norris described conservators as acting among “the physical, chemical, and ethical factors—the ecological niche— that an object of contemporary art may require to survive.” Dreams of stability and real, unstable materials are the pri mary foundations of this vexing and meticulous territory, loaded with responsibility, where old mistakes and over-polishing can never be forgotten.

唐纳德·贾德,《15 件无名混凝土作品》,2.5 × 2.5 × 5 m,1980–1984 (局部)。永久收藏,辛那提基金会,马尔法,德克萨斯州(照片由 道格拉斯·塔克拍摄,2009,图片由辛那提基金会提供。作品版权属于贾德基金会/由纽约 VAGA 授权) / Donald Judd, “15 untitled works in concrete”, 2.5 × 2.5 × 5 m, 1980–1984 (overview). Permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas (Photo by Douglas Tuck, 2009; courtesy of the Chinati Foundation. Art © Judd Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY)

唐纳德·贾德,《15 件无名混凝土作品》,2.5 × 2.5 × 5 m, 1980–1984(局部,展示了混凝土中的裂痕)(照片由辛那提 基金会保存工作室拍摄)/ Donald Judd, “15 untitled works in concrete”, 2.5 × 2.5 × 5 m, 1980–1984 (detail showing crack in the concrete) (Photo by Conservation Studio, the Chinati Foundation)

Although his work is not strictly “contemporary,” Donald Judd is an artist whose commentaries and legacy are some of the more sonant on this subject. In his articles on “Complaints” (Parts I and II, 1969 and 1973) and “Installation” (1982), Judd vented his frustration with the way artists and their works were treated amid the mechanisms of exhibition and other art world dynamics. A combination of these gripes and his discomfort with the way his work was coerced into different and unsuitable spaces and rotated in and out of temporary exhibitions in New York moved Judd to establish a place where his work—and later that of others including Dan Flavin, Ilya Kabakov, Roni Horn, Robert Irwin, and Claes Oldenburg—could, in his own words “last in its first condition” (“In defense of my work”, 1977). Ann Temkin reminds us that Judd saw the pieces he created as unique and exact, and that it was in their very nature to remain “unmediated”—that is, permanently installed away from outside “insults” (as she terms it) and abuse. Those who work on Judd’s work now must accept that some of the materials he used are “to varying degrees inherently unstable”—regardless of the stability of his vision.

In Marfa, Texas, Judd—the exquisite carpenter of space (a description he would no doubt have objected to, just as he resisted being seen as the leading exponent of minimalism)— found a site for his primary studio and home. He reputedly settled on the area by drawing concentric circles on a map, choosing the place where he could draw the largest circle containing the fewest people. His move to Marfa—a small, whitewashed town in West Texas, now of about two thousand people—and the establishment of an expansive studio compound known as “The Block” in former army buildings is still regarded with contention by some local residents. Judd’s vision for his living and studio space, begun in earnest in 1974, and later for the Chinati Foundation, where work began to install pieces by Judd, John Chamberlain, and Dan Flavin in 1979, was meticulous. He could spend two years planning a room, as he said, “thinking and moving pieces around.” At The Block, he realigned a door by a foot or so to better open onto a grouping of his early pieces.

唐纳德·贾德,《100 件无名磨铝作品》,104 × 129.5 × 183 cm,1982–1986。永久收藏,辛那提基金会,马尔法,德克萨斯州(照片由道格 拉斯·塔克拍摄,2009,作品版权属于贾德基金会/由纽约VAGA授权) / Donald Judd, “100 untitled works in mill aluminum”, 104 × 129.5 × 183 cm, 1982–1986. Permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas (Photo by Douglas Tuck, 2009, Art © Judd Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY)

Judd died in 1994 when he was sixty-five. Knowing that he would not return to Marfa, he instructed in his will that everything be kept exactly as it was. Piles of books in his library sit as they were left by Judd or his assistants, awaiting his return from a trip to New York which would never come, their bereft pages gradually cur ling up. Overhead in the afternoon, the corrugated iron roof creaks continuously, contracting as it cools with the disappearance of the sun. Meanwhile, those objects which had never anticipated being moved again stand in the landscape and in the repur posed army sheds at Chinati Foundation. For Judd, the placement of an artwork was as intrinsic to its understanding as the object itself.

On a recent visit to Marfa, I found myself musing on the relationship between Judd’s fervent vision for permanence and the natural environment that moves it. Between 1980 and 1984, the famous fifteen concrete works, cast to the millimeter, were placed outside on the ground in a highly specific arrangement. James Lawrence describes them as “solid form that simultaneously asserts an irreducible and abstract geometric fact—horizontality—and … the real terrain that can be directly felt.”1 There is nothing passive about the way these works were conceived; theirs is deliberate interaction with the landscape and the gradient of the ground. Over the years, the concrete works have been beset by bats, dust, burrowing animals and soil subsistence, water and vegetation—in short, the machinations of nature’s own continuous imperatives.

In the artillery sheds, the “100 untitled works in mill aluminum” of 1982–1986 incur their share of environmental affect. There is no climate control anywhere on the Chinati site; the sheds’ roofs and windows are not airtight, so the temperature fluctuates. The works heat up in the morning from the east and from the west in the evening. They walk—some more than others—in all different directions thanks to tension which results from the heat. Adopting the length of view that conservators must project in trying to preserve them, one might begin to imagine the slow but certain dance of these two-hundred-pound objects about the floor, undetected until a “footprint” is left behind, and someone must decide what’s to be done.

唐纳德·贾德,《100 件无名磨铝作品》, 104 × 129.5 × 183 cm,1982–1986(局部,展示了#28, 棚屋北面,西排,地板上的运动)。永久收藏,辛 那提基金会,马尔法,德克萨斯州(照片由辛那提 基金会保存工作室拍摄) / Donald Judd, “100 untitled works in mill aluminum”, 104 × 129.5 × 183 cm, 1982–1986 (detail showing #28, North Shed, West Row, movement on floor). Permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas (Photo by Conservation Studio, the Chinati Foundation)

Realistically, artists themselves cannot picture what will happen to their work over time—or how rapidly. “School No. 6”, an abandoned Soviet Union school house imagined by Ilya Kabakov, occupies a full building on the Chinati site. When it was ori ginally installed in 1993, Kabakov had wanted to leave the work to decay on its own, and there were no doors or win dows on the courtyard-facing sides of the building. By 1996, when a new inventory showed how the faded papers, insect specimens, old photographs, strategically placed twigs, furniture, and posters that comprise the contents of the school had already decayed significantly, Kabakov was asked what he wanted to do, and a decision was made to make some concessions to protecting the work. Now, UV protective window glass and the replacement of some items ensure the school will last a little longer in its strange state between cultivated neglect and grudging conservation: it may decay—but not too much.

伊利亚·卡巴科夫,《学校 6 号》,综合材料,尺寸可变,1993 。永久收藏,辛那提基金会,马尔法,德克萨斯州(照片由辛那提基金会 保存工作室拍摄) / Ilya Kabakov, “School No. 6”, mixed media, dimensions variable, 1993. Permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas (Photo by Conservation Studio, the Chinati Foundation)

伊利亚·卡巴科夫,《学校 6 号》,综合材料,尺寸可变,1993(照片展示了砖下被替换的纸张,1号房间)。永久收藏,辛那提基金会, 马尔法,德克萨斯州(照片由辛那提基金会保存工作室拍摄) / Ilya Kabakov, “School No. 6”, mixed media, dimensions variable, 1993 (photo shows replaced paper under brick, room 1). Permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas (Photo by Conservation Studio, the Chinati Foundation)

In a neighboring building, Roni Horn’s identical solid copper cones, too, remind one of the private lives of these works. “Things That Happen Again: For a Here and a There” (1986–1991) lie on the floor some feet apart, conversant but at angles. Each year, two people must spend at least two days on hands and knees to polish them, for their patina must be even and the same. Their pristine appearance belies the many insect marks that have disturbed them. Like heavy russet birds, each night they are covered with special, custom- made cages to keep the pests out, and unveiled again each mor ning to emit their site-specific minimalist message.

罗尼·霍恩,《事情反复发生,为一在此者,一在彼者》,实心铜,每个的直径是 34.2 cm 逐渐减少至 30.5 cm,1986–1991。从贾德基金会 长期租借,辛那提基金会,马尔法,德克萨斯州(照片由佛洛里安·豪泽尔拍摄,2001,图片由辛那提基金会提供,版权属于罗尼·霍 恩,纽约) / Roni Horn, “Things That Happen Again: For a Here and a There”, solid copper, each 34.2 cm diameter tapering to 30.5 cm, 1986–1991. On long-term loan from Judd Foundation, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas (Photo by Florian Holzherr, 2001; courtesy of the Chinati Foundation. © Roni Horn, New York)

罗尼·霍恩,《事情反复发生,为一在此者,一在彼 者》,实心铜,每一个的直径是34.2 cm 逐渐减少 至 30.5 cm,1986–1991(照片展示了北面的作品,另 一个被隐藏)。从贾德基金会长期租借,辛那提基金 会,马尔法,德克萨斯州(照片由辛那提基金会保存 工作室拍摄) / Roni Horn, “Things That Happen Again: For a Here and a There”, solid copper, each 34.2 cm diameter tapering to 30.5 cm, 1986–1991 (photos show the work on the north side, covered). On long-term loan from Judd Foundation, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas (Photo by Conservation Studio, the Chinati Foundation)

On the three-hour drive from Marfa to El Paso for the airport, one passes Elmgreen and Dragset’s “Prada Marfa”, a permanent installation inaugurated in 2005, and one of the most photogenic outdoor artworks ever made. This, too, was conceived to be left alone from the outset to decay, yet (following break-ins, vandalism, and insect invasion, among other troubles), it also was placed on a conservation list. Now, there is again talk behind the scenes of leaving it to its fate.

Where human decisions hover around conservation and benign neglect, however, these artworks continue. Suspen ded between original dreams of per manence and a still-abstract—but none the less romantic—threat of future ruin, it is their present which can seem most remote.

伊利亚·卡巴科夫,《学校 6 号》,混合媒介,尺寸 可变,1993(局部,展示墙面卷起的墙漆)。永久收 藏,辛那提基金会,马尔法,德克萨斯州(照片由 辛那提基金会保存工作室拍摄) / Ilya Kabakov, “School No. 6”, mixed media, dimensions variable, 1993 (details showing lifting wall paint). Permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas (Photo by Conservation Studio, the Chinati Foundation).

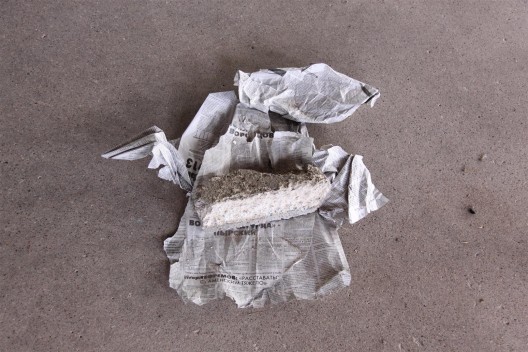

唐纳德·贾德,《15 件 无名混凝土作品》, 2.5 × 2.5 × 5 m,1980–1984 (局部)。永久收藏, 辛那提基金会,马尔 法,德克萨斯州(照片 由道格拉斯·塔克拍 摄,2009,图片由辛那 提基金会提供。作品 版权属于贾德基金会/ 由纽约 VAGA 授权)/ Donald Judd, “15 untitled works in concrete”, 2.5 × 2.5 × 5 m, 1980–1984 (detail, braced). (Photo by Conservation Studio, the Chinati Foundation)

Notes

1 James Lawrence, “Donald Judd’s Works in Concrete”, Chinati Foundation Newsletter 15 (October 2010): 8.