Our readers may still remember—or not—the excess of saccharine and excessively refined art on view in galleries, art fairs, and museums in 2012. No surprise, there: though not particularly memorable, such works were never far from hand. In the year that has just passed, though, viewers crawling through art spaces might have sensed a strong sense of “revival”—of the past, of the “good old days.” Rather than an engulfing trend, it was more a quiet sprinkling of works that made their way into the four corners of the contemporary art world in China—perhaps even creeping up on the collective consciousness of creativity. Much as the Beijing winter has been very mild this year, overall, the art of the past year has also felt rather milder and more sentimental from previous years. Let us then explore the production and exhibition of this “old” contemporary art in the most vibrant and active part of the contemporary Chinese art world, Beijing.

One first point to clarify is that the aim here is to explore works with this “revivalist” tendency which appeared in various contemporary art spaces over the past year—even if the works were not necessarily created but merely exhibited in the past year. In contrast, certain galleries or artists normally exhibiting or working in ink will be excluded from this discussion. These rules have not been set up arbitrarily; such limits set a “frame” to filter out the many unconnected or unimportant factors (examples include such truisms as “the rise of local collectors,” “the rise of nationalism,” “the search for cultural identity,” or “cultural renaissance”). In this way, we can pose a more interesting question: What does it mean when “contemporary” art avoids the contemporary? Additionally, the intent is not to interpret the particular meaning of a work or the symbolic significance a creator grants the work, because usually, these interpretations are not necessarily (or necessarily not) accepted by the artists themselves. Furthermore, curators and writers of catalogues have already perfected the language used in expounding and blowing up a work’s significance, rendering any further contributions on my part superfluous. Thus, the main focus here is to explore the reasons behind this “revivalist” trend and the signals presented from this phenomenon. I would like to believe that if a certain artist produced experimental work in the 1990s, played with political symbolism in the 2000s, and then suddenly experienced an overwhelming desire—an internal desire—to contemplate “tradition” in the 2010s, then his or her sincerity should not be doubted too much—since individually, they may very well be sincere.

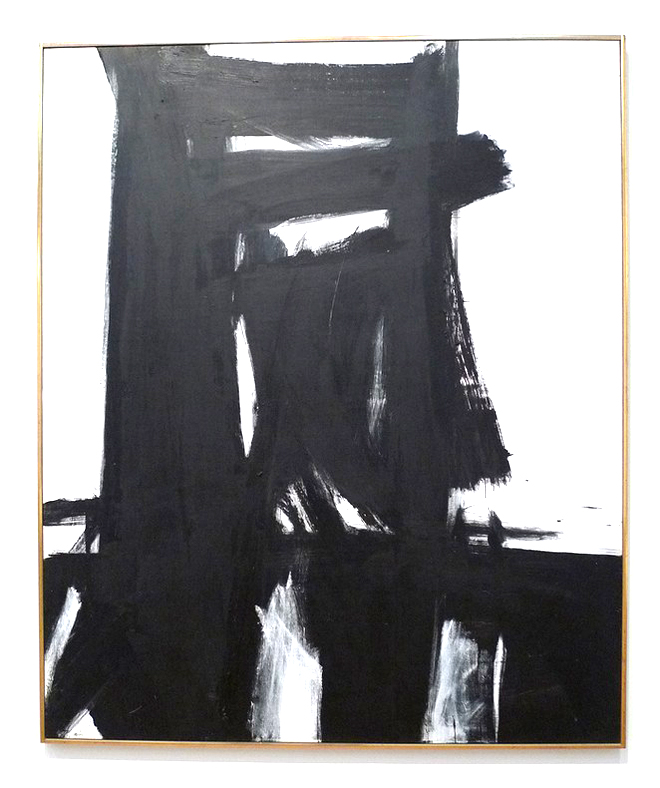

Installation view, “Guansha Gathering”, Chambers Fine Art (Beijing), 2013.

《冠山风》,展览现场,前波画廊(北京),2013(photo: Chambers Fine Art)

First, let us start with the venerated and millennial practice of Chinese calligraphy. If, a few years ago, there were still academics debating whether Chinese calligraphy ought to be defined as a form of visual art or rather as a cultural relic, then based on last year’s showing, Chinese calligraphy has answered that question most definitely and resoundingly—it is art! And even contemporary art. As I had mentioned in another article, calligraphy has not entered contemporary art because it has undergone a face-lift, so to speak (as performance art, for instance, its readability is practically nullified); rather, it is the definition of contemporary art which has been further expanded. In contrast to other official calligraphers under state patronage, Wang Dongling (director of China Calligraphers Association) was very active in contemporary art circles last year. His joint exhibition with Zheng Shengtian (former chair of the oil painting department at the China Academy of Art, and now Editor in Chief of Yishu), at Chambers Fine Art in Beijing (Jul 13–Sep 1, 2013) is currently also in progress at Chambers Fine Art’s New York Space (“Guanshan Gathering,” Jan 1–Feb 22, 2014). In addition to this, Wang had a solo exhibition at Ink Studio (“Wang Dongling: The Origins of Abstraction,” Nov 9, 2013–Jan 5, 2014), and is taking part in the inaugural exhibition at OCAT Xi’an (Nov 4, 2013–Feb 28, 2014). He also participated in “Those Leading Contemporary Art Practices—A Juried Invitational Exhibition of the Award of Art China” (Today Art Museum, May 4–18, 2013) which also included Liu Xiaodong, Wang Guangle, Cui Xiuwen, Qiu Zhijie, and Xu Zhen, among others. Equally, many “typical contemporary artists” (a refutation of this definition would only serve to illustrate my point) seem unable to sit still on the sidelines, diving into the fray with “Calligraphy by 19 Contemporary Artists” (01100001 Gallery, Sept 28–Nov 12, 2013), which included Chen Liangjie, Chen Xiaoyun, Chen Wenbo, Jiang Zhi, Mao Yan, Birdhead, and others.

Just what is it that makes today’s calligraphy so different, so appealing? From a purely stylistic viewpoint, some of Wang Dongling’s calligraphy and illustrations closely recall works by the abstract expressionist Franz Kline (1910-1962), but such is not the source of Wang Dongling’s contemporaneity. Kline’s work exhibits a certain “orientalism” while Wang Dongling’s abstract calligraphy is firmly grounded in his training as well as the native lexicon of Chinese calligraphy—firmly embedded within the local system. The use of calligraphy as a tool for communication between merchants and officials has already become some kind of a tradition. For at least a decade, it has entered into the discussions of contemporary art as a certain resource (1), but its recent mass influx into contemporary art spaces is unprecedented.

Cai Guangbin, “Selfie—Girl”, 180 x 200 cm, ink video, 2013 (Today Art Museum).

蔡广斌,《自拍-女孩》,180 x 200 cm,水墨影像,2013(图片来自今日美术馆网站)

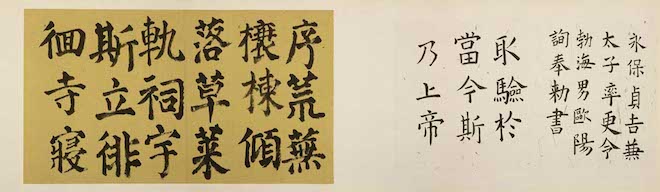

Left: BIRDHEAD/Song Tao, “Drawn from Inscriptions of Master Yan Zhenqing”, 43 × 80 cm, 2013; Right: BIRDHEAD/Ji Weiyu, “Drawn from Inscriptions of Master Ou Yangxun”, 35 × 75 cm, 2013.

左:鸟头小组 宋涛,《临颜真卿颜氏家庙碑》, 43 × 80 cm,2013;右:季炜煜,《临欧阳询九成宫醴泉铭》, 35 × 75 cm,2013

In contrast to this relatively sudden “garrison” of calligraphy, ink and other traditional elements have long been habitués in contemporary art—perhaps, more accurately, they are the new masters. Even artists like Zeng Fanzhi, Fang Lijun, and Luo Zhongli who were cutting-edge back in the day seem to harbor a deep interest in ink. What is most ironic is how even the “Cartoon Generation” (katong yidai) of the early 90s—so called for their reactions to consumerism and mass media—is starting to be infatuated with ink. Huang Yihan’s “Ronald McDonald” is still around—only he has been splashed in ink. Elsewhere, Hong Hao’s Elegant Gathering (2007) series foregrounds photorealistic figures on a traditional landscape painting (Pace Beijing, Mar 16–Apr 27, 2013). Qiu Zhijie recently held a solo show, “Satire” (Galleria Continua, Sep 26–Dec 1, 2013) which included a map made up of six painted scrolls, along with intricate carvings of figures of the Buddha and various beasts. In essence, Hong Hao’s show was no different from Qiu Zhijie’s, because they both ended up moving closer to tradition in the name of reflection and deconstruction of tradition. Works along the same vein include Shi Jinsong’s “Double Pine Tree Garden” (White Box Museum of Art, “‘Civilization’ Round I: Lin Lv,” Dec 22, 2013–Feb 15, 2014), which incorporates traditional imagery through brick imitations of stone benches and of Taihu rocks. Meanwhile, He Sen repeated his showing from the previous year by exhibiting yet another oil painting done in the style of a traditional ink painting, “Night Rain Approaches” (“Ye Yu Jiang Zhi,”2013).

Other examples include the mishmash of ink, political pop, kitsch, and cartoon in “Ink Logic—25 Artists & 25 Expressions” (ESSE Space, Jun 16–Jul 7, 2013); landscape paintings and Chinese seals seen in Zhang Zheyi’s “Rain Cloud Over Wushan No. 3” (“Altered Shan Shui States,” Red Gate Gallery, Mar 25– Apr 24, 2013); sculptures of ancient buildings rising upright from pools of ink or blossoming from mushroom clouds, exhibited in Liu Jiahua’s solo show “My Own Castle” (All Art Center of Contemporary Art, Dec 1–23, 2013); imposing landscapes by the “state first-rate painter” (Guojia Yiji Huajia) Jia Xiangguo in “Collection of Great Landscape by Painter Xiangguo Jia” (798 Art Bridge Gallery, Jun 29–Jul 18, 2013); the mood occasionally achieved with solid blocks of color and ink in the exhibition by Tang Chenghua (lecturer in the printmaking department at the Central Academy of Fine Arts) curated by Peng Feng (SZ Art Center, Jun 8–28, 2013); and the use of the seven iconic structures along Beijing’s axes—including Qianmen, Tiananmen, the Drum Tower—in installations for Wu Daxin’s exhibition “De Composure” (Tang Contemporary Art, May 18–Jun 30, 2013).

“A New Spirit in Ink,” an exhibition (2) held at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Beijing (Oct 9–Nov 9, 2013) did not provide any new insight into the medium or exhibit the “spirit” of ink through the works on show, which included a wall of black stones (Ding Yi, “Rolling Stone,” 2013), splashes of ink on a white fabric from a shirt and broken blue and white porcelain vases (Li Guangming, “Use Hull to Get the Soul Back,” 2013). In fact these works overused the medium of ink. Unfortunately, the list of similar exhibitions last year goes on and on: “In the East” (SZ Art Center, Dec 3–20, 2013), “The Taste of Ink” (Amy Li Gallery, Nov 3–Dec 29, 2013), “New Ink Indicator” (New Ink Image Gallery, Dec 15, 2013–Jan 15, 2014).

There is often a clear and obvious basis for a revival of or retrospective look at the past—as in the case last year when there was again a keen focus on the debate between the Northern and Southern schools (first raised by Dong Qichang in the Ming Dynasty). If shows held by official institutions such as the National Art Museum of China (“New Northern School Chinese Landscape,” an exhibition of Shi Enzhao’s works, Dec 30, 2013–Jan 9, 2014) or the retrospective on Dong Qichang at Yan Huang Art Museum (“South and North Schools of Chinese Landscape Painting,” Jun 22–Jul 6, 2013) were exhibitions which arose from these official artists’ simple longing to go back to their roots, then “Bye, Mr. Dong Qichang” (the Qi Lan solo exhibition at A Thousand Plateaus Art Space, Dec 28, 2013–Feb 28, 2014) reflects an artist’s struggle between the desire to express himself and the restrictive burden of tradition. Of course, goodbye (zaijian) is not a final farewell (yongbie) but an implication of reunion, and Qi’s show is no a declaration of personal intent but rather hints at the overall cultural logic in the present day. Praised, overthrown, and then reclaimed as an “indirect way to save the nation”—used as a model, and then abandoned yet again—why has Dong Qichang’s influence been able to survive so much upheaval? Perhaps his keen observation of bureaucratic officialdom as well as the (imagined) escapism of the Southern school suit the desires of the current (but not contemporary) group of ink painters, in a way that spans history (3).

This “tradition” endorsed by ink seems to sparkle both inside and out. Externally, ink art has earned official support and foreign appreciation as an ambassador of Chinese culture on the rise; internally, ink art profits from huge support of capital as a link between the business and official worlds. Whether ink, “experimental ink” or “ink experiments,” all of these constitute a politics of form. To illustrate: no matter how much artists “experiment” with experimental ink, they dare not depart from the duality of black and white, and so the result is a stream of ink “derivatives,” forever renewed. Of course, a collector may purchase a high-end experimental ink work to hang at home out of personal interest—and indeed may never be inclined to re-sell it—yet this still adds symbolic value.

Installation view, “Sunflower: Liu Qinghe Solo Exhibition”, Hive Center for Contemporary Art, 2013 (photo: Hive).

“向阳花:刘庆和个展”,现场,蜂巢当代艺术中心,2013(图片来自蜂巢艺术中心网站)

A “whipped” work by Yang Xinguang, ink on paper, from “Superfluous Thing VIII”, Hive Center for Contemporary Art, 2013.

杨心广,“抽”像画,2013,来自展览“长物志第八回”, 蜂巢当代艺术中心, 2013(图片来自蜂巢艺术中心网站)

Among the many contemporary art institutions, there are two obvious converts to “tradition”: Hive Center for Contemporary Art and Today Art Museum. After the Hive Center’s scandal, they had two exhibitions focusing solely on ink last year—“Sunflower: Liu Qinghe Solo Exhibition” (Dec 21, 2013–Jan 21, 2014) and “Illusion: Contemporary Chinese Ink Arts Series I” (curated by the Chinese art historian, Shen Kuiyi; Jun 22–Jul 22, 2013). Besides these, most of their exhibitions—including Lei Ziren’s “Mis-Painting” (Sep 14–Oct 13, 2013), Tu Hongtao’s “The Road Not Taken” (Aug 3–Sep 2, 2013), Dong Wenshen’s solo exhibition, “Memories in Silver” (Nov 30–Dec 15, 2013) clearly and unmistakably expressed their interest in the traditional. Besides these, the Hive Center also put forth a series of exhibitions entitled “Superfluous Things,” the title originating in the works of Wen Zhenheng, a great grandson of the Ming Dynasty painter Wen Zhengming. The eighth show in this series (Dec 21, 2013–Jan 21, 2014) featured Yang Xinguang’s works made by flailing an ink-covered whip over paper—an “integration” of abstract expressionism and ink. Of course, ink differs essentially from Abstract Expressionism. One significance of Abstract Expressionism is a departure from the easel, while its de-centered image constitutes a subversion of tradition. Yet the focus of Yang Xinguang’s works is closely and materially linked to ink, and additionally can be said to be a return to tradition. The play on words (“whip” sounds like the first part of “abstract” in Chinese) only adds a few dashes of “contemporary flavor” into the inky mixture.

In contrast, Today Art Museum—“China’s first private, non-profit museum”— (according to their official website) seems to have become more correct, with a clearer grasp on the concept of tradition. Over the last year they had a panoply of ink exhibitions great and small, including “The Method of Water and Art Ink Inspirations,” a large-scale invitational exhibition (Dec 18– 29, 2013), “Painting for Stimulation–Guan Jingjing Solo Exhibition” (Dec 13–19, 2013), “New Prominence from the Academy: Exhibition of the Nominees of China’s Contemporary Ink Wash Artists 2013” (Nov 16–26, 2013), “Zhu Wei solo exhibition” (Nov 3–10, 2013), Yang Jian’s solo ink exhibition (Sep 29–Oct 9, 2013), among others. It would be biased to attribute Today Art Museum’s tendency towards ink as somehow related to Gao Peng (Alex Gao), the executive director newly appointed last August (while the former, and quite simply, mediocre executive director, Xie Suzhen, was once at the helm of CAFA Art Museum), because the “revival” of “tradition” is not merely an individual inclination nor a particular current of thought at a particular period. Rather, it is an illustration, in visual form, of the aggregation and materialization of official, institutional power.

In the past year, we have seen a surfeit of ink exhibitions in contemporary art spaces (which was not only limited to Beijing); such exhibitions seemed to have adopted terms like “new,” “experimental,” “transformational,” “conceptual,” or “contemporary.” Still, even if spaces and institutions which were previously rather more experimental have now started to exhibit ink art in volume, this gives little cause for criticism—just as once-extreme performances have now been accepted within contemporary art. Although contemporary art was once in an imposing position—in the limelight, even—in comparison to the famous calligraphic works cropping up in auctions and within official circles, it appears all too weak. We cannot lose sight of one basic fact: galleries, no matter how much they emphasize the intellectual and experimental, first and foremost reflect market demands. Hence explaining the phenomenon of so many “revivalist” works in galleries over the course of a year comes down not to discussing which artist created what work but to a diagnosis of the sign of the times.

Revivals have had historical precedents; “revivalism” is not unique to the present. As Professor Li Ling noted in his study on “revivalist” art in ancient China, the shift to “revivalist” art (art in imitation of the past) typically involves three stages: the first is a strong, underground stimulus (inter alia), which secondly sparks inspiration and imitation of the antiquities of the past, and third, towards the longing and imagination of the past (4). Therefore, artistic and cultural revivals are highly selective phenomena. They are often called upon when the power of an elite class needs to be consolidated by invoking a pre-defined patriotism and amplifying a sense of national identity, or when a culture’s vitality is sapped (due to political and ideological reasons) and the society enters a state of cultural conservatism. From a cultural perspective, the resurgence of ink art is due to its perception as a calling card for tradition. From an institutional perspective, when tradition is defined in terms of a specific style, it becomes irrelevant whether the products of this traditional style have anything indeed to do with tradition. Ink has gone down this precise route: after the collective fog of exhibitions, auctions, transactions, and collections, it has been transformed into a symbol of mainstream consciousness. It no longer matters if it is good or bad; what is important is that it is wedded to a certain politics and system.

Therefore, the crux of the issue lies in clarifying what is “contemporary” and what is “traditional.” Certainly, “contemporary” is not the same as “current” or “of the moment,” because “contemporary” encompasses far more than the temporal in much the same way that the “modern” in “modernism” and is a particular judgment, aesthetic or otherwise. Various movements in history have always engaged in the debate of “the traditional vs. the modern,” from the “Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns” in 17th-century France to the May Fourth Movement and the “Cultural Fever” of the 1980s in China. Some emphasize the past while downplaying the present while others do just the opposite, but this phenomenon only occurs when these two ideologies are evenly matched. We must also acknowledge that “contemporary” and “traditional” possess significance in terms of value, while having relatively little to do with time despite the reference to the passing of time in both terms. The concepts of “tradition” and “contemporary” are both constructs of the imagination and institutions. As Li Wei’s end-of-year exhibition “Thank God” (Gallery Yang, Dec 21, 2013–Feb 16, 2014) alludes, various forms of the “sacred” and the “mysterious” are actually fabricated with cheap materials. The avant-garde mask of “contemporary art” and the sage-like pose of “traditional art” are no exceptions. I cannot presume to define what contemporary art is, but I suspect this spirit of ignoring the present while exciting the imagination by building up ancient forms in order to create a pile of nonsensical drivel is pointedly not contemporary art.

Focusing on the dialectic between the “contemporary” and the “revivalist” is an oft-used strategy in transplanting “revivalist” art into contemporary art spaces, but this process actually blurs the line between the two, and is instead becomes a strategic cultural nihilism and borders on sophistry. No matter how multitudinous the various definitions of “contemporary art,” at the very least “revivalism” implies a diminished concern for the present and a surrender to cultural conservatism. Having become an official symbol of art, ink art is certainly popular in official circles, and yet at the same time, it cooperates with contemporary art—and so ink inevitably becomes overpowering. It only requires a whiff of the contemporary to occupy an entirely different field of art, while contemporary art must compromise its soul. When Fang Lijun becomes part of the official system he once mocked, when the art world is flooded with artists who are new but not fresh, who rely on the revival of the past to earn a living, we could still say contemporary art is bouncing back.

There are indeed more galleries again in 798 after the dip caused by the financial crisis a few years. However, contemporary art was left shaken by this near-miss, and has come to understand how unstable relying on the market could be. Regardless of what the financial crisis taught contemporary art, the lesson came at a great cost to experimental and “contemporary” art. The lesson: laobans (local bigwigs) are more dependable than the laowai (foreigners), while laoye (“The Man,” or officials) is the most dependable of all. Having learned this lesson, contemporary art will be delighted to see officials’ power drastically expanding at a monopolistic rate. Still, contemporary art finds itself in an awkward situation because it has encountered what Michaud calls a “conceptual crisis,” but the “last words” of Chinese contemporary art are not so metaphysical as that of France. Here, it is a pure substitution of the content, tools, media, and style of today with those of the past. Thus, it seems the line of defense which “contemporary art” is attempting to raid is, in fact, non-existent (“‘Raid’ the Last Line of Defense,” Guozhong Art Museum, Oct 1–15, 2013).

In fact, when exploring the reasons for the appearance of “tradition,” the oft-repeated “rise in domestic collectors” is a crude and superficial analysis. Undeniably, there has been a “rise in domestic collectors,” but this does not explain the root cause of the resurgence in “tradition.” In the expanse of Chinese history, artistic taste has almost always been dictated by officials, whether in terms of the role painting and calligraphy played in the gathering of scholars or the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou and their salt merchant patrons. To exaggerate only a little, contemporary art is only a flash in the pan. In its most profound sense, it is but an infinitesimal reflection of the ongoing struggle between conservative and liberal elements within the elite grouping in power, played out on the battlefield of the visual arts. Once the conservative elements take up all the space in politics and culture, a fundamental root cause for the downfall of contemporary art can be found. Both overwhelmed and begrudging, “contemporary” art must yield space to this greater force.

All of this was expected; only ink has not only seeped into contemporary art spaces, but public spaces as well—traditional Chinese painting used in advertisements, seen in subway stations, bus stops, LED panels on skyscrapers, train stations, and so on…. It is as though contemporary art has re-awoken from a three-decade-long dream to find itself back where it began—from an impoverished marginalization to a more sumptuous marginalization. The signals sent out by ink art are an expression of the influence that an official, bureaucratic order has on contemporary art, because the space for contemporary language and ideas is constantly being compressed. So contemporary Chinese art occupies an uneasy space between a rock and a hard place: isolation on one side, and on the other, prosperity—at the cost of renouncing its own identity.

References:

(1) Yang Yingshi, Calligraphy as a Resource: A New Direction for Chinese Contemporary Art, Journal of Guizhou University (Art Edition), 1st edition, 2002.

(2) Ammonal Gallery, situated near the Summer Palace in Beijing was the previous incarnation of Beijing MOCA; it was one of the first galleries established in Beijing. The “First Joint Exhibition of Chinese Professional Painter’s Works” was held here in 1993, and many of the exhibiting artists came from the Yuanmingyuan Artist Village. This means we can go online to find a certain photograph of the artist Zhang Shengquan (who committed suicide on January 1, 2000). The photograph shows him standing in front of the gallery entrance where a notice shutting down his exhibition is pasted; it reads “W.R exhibit cancelled.”

(3) There has been more focused research on Dong Qichang in recent decades, including the “International Symposium on Dong Qichang” held in Songjiang by the editorial department of the journal, Duoyun, and the “Tung Ch’i-ch’ang International Symposium” held at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in 1992. Important papers from the two symposia were collected in an anthology by Duoyun in 1998

(4) Li Ling, Shuo Gu Zhu Jin, Joint Publishing HK, 2007, page 11.

(5) (French) Michaud, Yves. The Crisis of Contemporary Art. Wang Mingnan (Trans.). Peking University Press. 2013. Page 171.