The exterior of this former theme park is a chromatic nightmare. A monstrous fabricated rock terrain, the geological terror fortifies the premises in a throbbing sprawl of blood red and sickly yellow. Upon its terraced slopes festooned with bougainvilleas and ferns is perched, to the right, a tubby smiling Buddha, and on the other side, a tiger crouched and flashing its fangs at a giant serpent. The paint is peeling; the cracks show. Yet miraculously, in the middle of the chaos there still stands, after all these years of abandon and disrepute, the name of this singular establishment: Haw Par Villa.

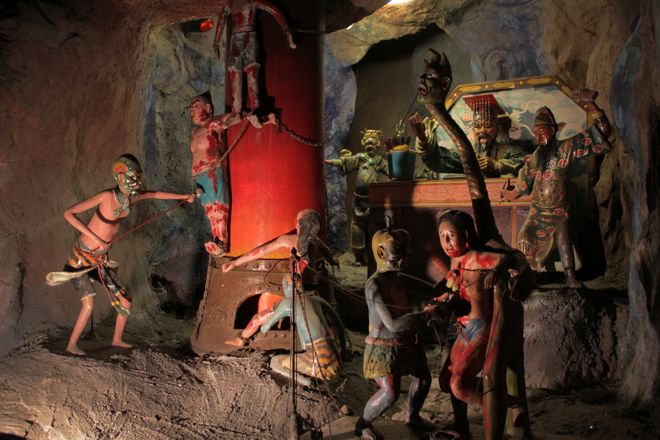

Gaudy. The word that springs up in any description of the time-battered garden complex in Singapore notorious for its numerous statues and dioramas depicting gruesome scenes culled from Chinese folklore and rendered in schlocky high saturation. For decades, its excesses have inspired horrified intrigue in locals and tourists seeking a transgressive alternative to the city-state’s more pruned developments. In fact, one can read the history of Haw Par Villa as one of its failed domestication by the Garden City. Originally built in 1937 by the Burmese-Hakka tycoon and proprietor of the Tiger Balm ointment, Aw Boon Haw, as a villa for his brother, the site was remade as a public mythological garden following the latter’s untimely death. It was a place where a syncretic mix of traditional Chinese, Taoist and Buddhist morals were made spectacular—a ghastly series of dioramas showing the Ten Courts of Hell or, just as disturbingly, a statue of Lady Tang suckling her toothless mother-in-law instead of her bawling infant. The Aw family’s subsequent neglect of the grounds motivated a government takeover in 1985, which transformed it into Dragon World, sold in touristic spiel as “the only Chinese mythological theme park in the world”. The folkish and idiosyncratic elements of Aw’s imaginarium were promptly removed to make way for a glorified narrative of Chinese history where Confucianism was the key reference point and the literati its protagonists. The venture failed within a few years. Since then, Aw’s unruly menagerie has been reinstated, standing today as both a monument to and ruin of its checkered past.

Haw Par Villa’s eclectic menagerie features an ensemble of unearthly creatures culled from Chinese folklore (photo: Ho Rui An)

The statues and dioramas of Haw Par Villa depict a syncretic mix of traditional Chinese, Taoist and Buddhist morals. (Photo: Ho Rui An)

But recent months have seen some stirrings of life, with a spate of exhibitions, performances and workshops taking over several of the park’s disused sites which have been refurbished and repurposed as art spaces. Behind this change is the curatorial collective LATENT SPACES, made up of artists Chun Kai Qun and Chun Kai Feng and programmer Elizabeth Gan, who stumbled upon the park’s abandoned Jade House and saw in it a potential exhibition space. It is not uncanny that it took such wayward wanderings to resuscitate the forsaken relic. The colossal collapse of Dragon World had branded the park as a place of failure. Investors shunned it, while a subsequent revitalization attempt by the Tourism Board as an overseas Chinese museum did not last.

“We wanted to let Haw Par Villa tell its own stories,” says Kai Qun, who believes that the path to revitalization lies not in foisting a single, over-determined narrative upon the space but in opening into as well as opening up the contesting histories already sedimented within. Haw Par Villa, as he points out, is a space of contradictions. While official accounts paint it as the philanthropic feat of a self-anointed pedagogue seeking to edify his less educated brethren, the villa was also a vanity project undertaken by a disgruntled industrialist from a minority dialect group to flaunt his wealth to a Hokkien-dominated diasporic community. Across the park, sightings of strategically planted Tiger Balm jar replicas further remind one that the place was also a shameless advertorial for the medicinal empire. Aw’s gift to his people was generosity reified in a pain relief formula.

Sai Hua Kuan’s contribution to “Nameless Forms”, 大小眼 (Dà xiǎo yǎn) (2013), a self-made camera obscura projecting an image of a found figurine.

(Photo credit: LATENT SPACES)

As a contemporary arts space, LATENT SPACES’s occupation of the historical monument inevitably produces tensions—tensions which, instead of being quelled, are mobilized to instigate new inquiries into the space. Notably, of the three exhibitions that have been mounted thus far, two have focused explicitly on issues of materiality and object-hood, though never in isolation from its immediate locality. Its inaugural show, “Nameless Forms”, considered what it means for form to be stripped of signification, with several artists working directly with material artefacts extracted from the park. Sai Hua Kuan’s “Daxiaoyan” (大小眼) (2013), for instance, comprises of a figurine of the Chinese goddess, Chang’e, which he found covered in holes left by an insect infestation. Sai installed a self-made camera obscura before the piece, literally exposing the latent material forces at work without rematerializing them as an image. Here, nature remains a ghostly trace resisting human capture. In the way it appeared to advocate a return to the things themselves, the exhibition sought to attune our senses to the very stuff that constitutes the park, its material life—a move that does not so much divorce the site from all context as it wrests it from the control of institutional mechanisms that have for the longest time tried to twist its crude matter in service of political exigency.

Such tactics of deterritorialization have resulted in rather minimal set-ups, creating a stark counterpoint to the park’s psychedelic displays. Kai Feng acknowledges that this has inadvertently made the gallery appear hostile to unsuspecting visitors, many of whom are not exhibition-goers. But he also sees the gallery’s emptiness as an invitation to dwell and invest time. This dimension of time came to the fore in the space’s second exhibition, “Materialized Time”, which took its inspiration from the ravages of time inscribed upon the park’s material surfaces. Featuring an eclectic collection of mainly sculptural works, each embodying a certain temporality through its very object-hood, the show examined how objects are constituted in time and by time. In João Vasco Paiva’s “Lumberyard Array #7” (2013), for instance, wooden beams that were previously used as table saw fences stand erect in the gallery in a fresh coat of blue paint, the history of its material abrasions contained in its fossilized incision. Above all, the show was also a plea to, quite plainly, give time to materiality, to carve out a space for a decelerated spectatorship within a landscape that has been reduced to photographic kitsch.

“Materialised Time”, group exhibition curated by Chun Kai Feng with participating artists Sookoon Ang, Chun Kai Feng, Chun Kai Qun, João Vasco Paiva and Jeremy Sharma.

(Photo credit: LATENT SPACES)

The current exhibition, “A Lifetime of Warranties”, is the first to take on the park as its key subject. In this solo exhibition of Kai Qun himself, gruesome imagery from the park is displaced onto the paraphernalia of modern living. An imposing formation of standing fans suspended from the ceiling have their turning heads wrapped in covers, each imprinted with a bloodied, disembodied head, while below, a B-horror film with a solitary fan as its principal cast plays on a flat screen television. It is a purgatory of comfort, a kind of perverse IKEA set where cushiness becomes oppressive. Through its acerbic take on the soul-sucking nature of consumerist culture, the work alludes to how Haw Par Villa itself fell victim to the crass commodification of culture in the late-nineties, leaving an indelible scar upon the national psyche. The artist relates how older cab drivers today still ask him if the harrowing S$16 entrance imposed then was still operational. The betrayal of Aw’s original vision—that of a public park free to all—has never been forgotten.

For most Singaporeans then, Haw Par Villa is like a lurid dream which, simply by refusing to go away, demands remembrance. Given its eccentricities, owed largely to the narcissism and dubious moral posturings of its founder, its place in history continues to be contested. Yet today, it seems a foregone conclusion that the park must remain despite all that is, as if its historical value lies precisely in its a-historicity, in how it exceeds all efforts at historicization. And as provisional as Haw Par Villa’s pasts is the future of the artist-run space hosted within its premises. LATENT SPACES’s current contract with the Tourism Board, which owns the site and also funded its renovation, ends in October. While a renewal is possible, the Board’s future plans remain uncertain. Surely, one fears to make any grand projections, given how this is a ground that has stolidly managed to overturn all attempts at mastering it, evading even the tentacular reach of global capital. An undead specimen bearing the traces of modernity’s disjunctures, the future of Haw Par Villa can perhaps only be imagined as a perpetual imminence—a latency.