Jia 嘉 (b. 1979) is an artist who lives and works in Berlin. She was born in Beijing where she studied architecture, performance and literature. In this conversation, Jia reflects on her development as an artist, the problems of translating artistic practice between differing social and cultural contexts and the intended critical significance of her work, which combines aspects of contemporary Western(ized) art with interpretations of traditional Chinese thought and practice.

Paul Gladston: I would like to begin by asking you to say something about the background to your development as an artist. In which ways has your varied training and experience had an impact on your work?

Jia: My father is a surgeon, and my mother a pharmacist who also works in a hospital. At least once a month, they were both called to work shifts on the same night. So, on those nights, from the age of four, I was left at home alone. Because they were so busy at work, they gave me a box of chalk besides other toys. I drew on the floor with the chalk, and after that I would clean the floor. I think this was the beginning of my interest in art. At the age of six, in 1985, I started to learn Chinese ink painting mostly by myself, though sometimes my father taught me. At twelve, my parents sent me to a weekend art school specially for students preparing for the exam to enter the Central Academy of Fine Art (CAFA) in Beijing. For almost three years, I studied Western drawing and painting. The art classes were held in the basement of CAFA, so we called it the “underground class.” At that time, being an artist meant being poor and living on dreams. Every year, CAFA gave only thirty places in response to more than a thousand applicants. Some tried for more than ten years, but you were not allowed to apply to university after the age of 25, so they had to change their ID cards in order to fake their ages. Most of the artists of our generation still remember that “underground class,” and still remember that art meant more to us than it does to students nowadays.

The only reason I did not go to CAFA like many of my friends and classmates was because of my parents’ divorce. I was good at science and technical subjects in high school, so studying architecture was the only choice open to me that would allow me to preserve some relationship with art.

I wanted to take the university exam again, and go to a better university for my second year, but my mother wouldn’t allow me to do it—I mention this only because it has an impact on my art work. So as soon as I entered university, I sought every possibility to attend classes in other universities, even though I was not officially enrolled. These “extracurricular” classes included architecture, philosophy and literature classes at Peking University, the film theory class at the Beijing Film Academy and the literature class at CAFA. At the time, there were no open courses online, but I was happily running from one class to another, through all those universities.

When I was twenty, I became vice-president of The Practice Society (Shijian She 实践社), the first organization dedicated to independent film in China. Later, the society was shut down by the government authorities.

But that was my golden years. I was so lucky to have been able to catch the end of the period when young people were still hungry for knowledge, and especially Western knowledge after the ending of the Cultural Revolution. I think all of us are still very proud of what we did for the Practice Society—not simply because we gave filmmakers such as Jia Zhangke, Lou Ye and others the first opportunity to show their movies, but because we knew we were doing the right thing to push Chinese film in a new direction. We dreamt of this, a cinema that would not just be for propaganda purposes. We acquired this passion once we got to see masterpieces on pirated DVDs.

Meanwhile, I tried everything to come back to art, including through postgraduate study of the literature and history of traditional Chinese opera and drama. I took jobs as an editor, public relations representative, curator, etc. After a while, I had more freedom to choose what I liked. I had been fascinated by traditional opera and modern drama for a long time.. Besides that, I love traditional Chinese literature. I recently set up a website for Chinese poetry. There is still only a small amount of material on the site, but it will grow. I liked writing and I was not bad at it, so my architecture history professor, Zhang Bo (张勃), asked me to co-author a book about classical Chinese gardens with him, Beijing Imperial Gardens (Beijing: Guangming Daily Press, 2004).

I now realize that this longstanding interest in Classical Chinese culture is not the norm for artists of my generation. I suppose this interest explains why all my works have a basis in traditional paradigms—or at least a consciousness of them—and a sense of loss at their destruction.

PG: You have stated that your work engages with ideas and practice initially developed in Western cultural contexts as a means of reinterpreting aspects of Chinese culture. You have also stated that the tension between differing cultural outlooks in your work acts as a generalized locus for criticism of Western and Chinese conditions. Could you discuss this further with reference to one of your artworks—for example, the series titled Chinese Version?

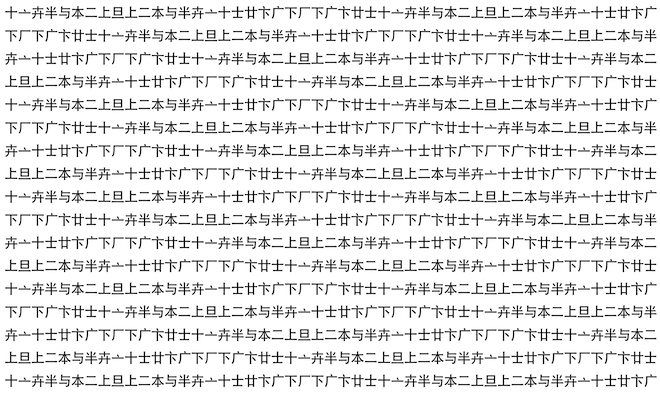

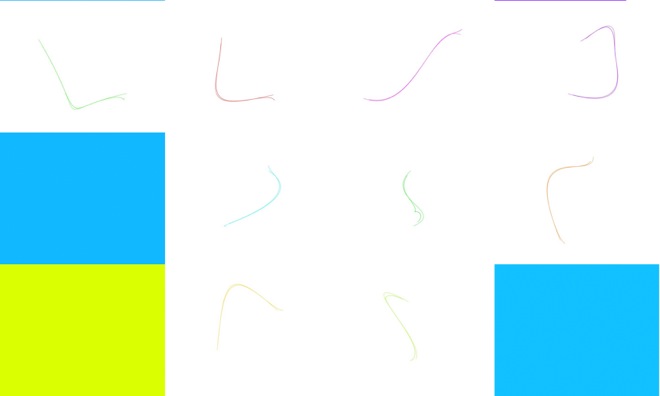

J: I visited Berlin and I found that I liked it, so I moved there in 2009. Since I have moved to Berlin, I have felt myself to be an individual for the first time; or rather, being so lonely. It took months to get used to life in Berlin and its diverse population. On one hand, since moving to Berlin, I feel that I’ve been losing my Chinese language.. On the other hand, English for me is still at the stage of being a simple tool, like a skeleton; it is more like a form instead of a rich inner emotion. The simplification of Chinese characters by the Chinese Communist Party in the 1950s—ostensibly as an attempt to improve communication between people of different classes and levels of education across China—was the greatest destruction of the Chinese language ever. Nowadays, less than 10% of traditional Chinese characters are left in use. My work The Chinese Version (ongoing from 2011) presents missing characters mixed with simplified characters in order to remind people of what we have lost and continue to lose. When I took out the semantic element of the Chinese characters in The Chinese Version the form remains; the overt pattern of the writing seems to suggest that everything is in order, but inside the content is disordered— this also reflects the impact of my suffering in moving between Western and Chinese cultures.

PG: Is your work intended to have an impact on society and culture beyond the limits of the institutionalized art world and its audiences? If so, what do you think that impact might be?

J: My favorite novel, Breakfast at Tiffany’s (Difannei Zaocan 第凡內早餐)—not the one by Truman Capote—was written by a Taiwanese woman writer called Chu Tien-hsin (pinyin: Zhu Tianxin; 朱天心). It’s about different attitudes towards the political situation in Taiwan seen from the perspective of two generations of Taiwanese female writers. The older one recalls the period when they joined the democratic movement against martial law in Taiwan and still strongly believes they were right to take the responsibility of the revolution upon their own shoulders, no matter the years in prison or the possibility of an even worse end; the younger one seems more worldly and shrewd, knowing that to be involved in politics means to risk your life, and that if you win, you will yield all your victories to someone you do not know at all who becomes the president and does whatever he wants. If you lose, you lose everything. In either case, how can you trust that person—why waste your life for him? I am just between those two generations. In a sense, I agree with both of them.

I once saw an interview with this same writer:

Q: Your work has always had a potential as duty…in order to show the magic of human imagination and creativity, and not to pretend to transform society.

A: I often feel that in the position of novelist, you need to reveal the crisis…I think you must first make a statement regardless of the consequences.

Anger and resentment is the largest source of my writing … I found that many people I once respected have yielded to compromise, surrender, and stagnation. It seems difficult to understand them. So I’m afraid to be a kindly person. If one day, my anger is gone, I might be a happy person, but I could no longer be creative.

For me that is the beauty of being a writer or artist.

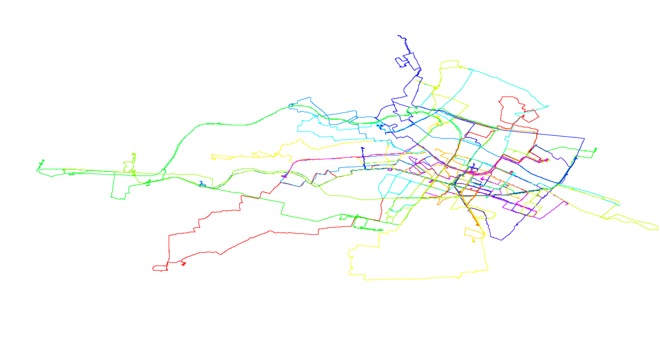

PG: Your recent works are characterized by techniques and a minimal aesthetic reminiscent of those associated with conceptual art of the late 1960s and 1970s; for example, the work “ORIENTATION I: Bicycle Tracks”, which maps your bicycle rides around Berlin. How did you arrive at those techniques and that minimal aesthetic, and how do they support your critical intentions as an artist?

J: Three years ago, I was with friends in their garden. A boy looked up at the stars and asked his father about astronomy. I was very sad when I saw it. I knew I had lost all knowledge astronomy I once had, and I have no father to ask anymore. Then it occurred to me that I had been avoiding all the subjects we were taught in China to think of as “boys’ subjects,” because I knew I would lose support from my father. From that moment, I decided to overcome the invisible gap between genders and any fear that comes from my childhood. With the progress of The Chinese Version series, I started to become interested in mathematics. From there, I learnt computer coding and became more interested in sciences such as biology, high tech and new materials. The world of science leads you towards another passion and aesthetic compared with the world of the humanities. Science and technology smoothly cover over my emotional traumas.

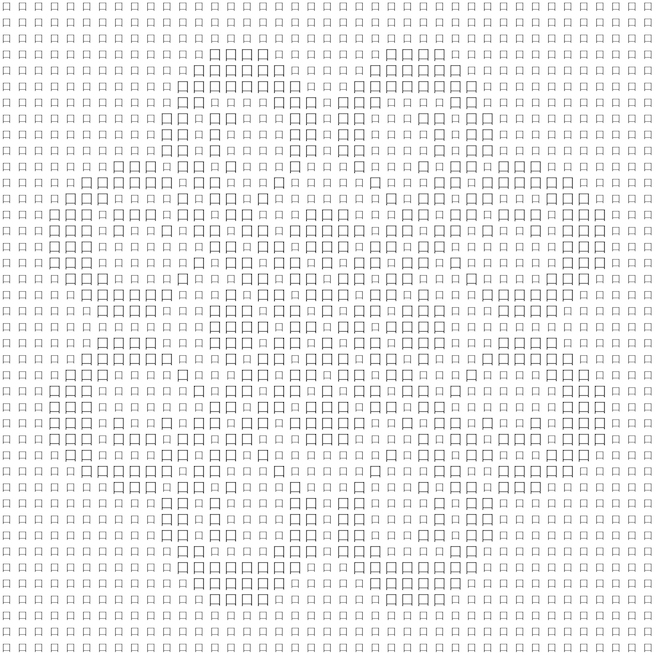

So using technology in works such as “ORIENTATION I: Bicycle Tracks” (2014) comes naturally. In my view, this tendency is a continuation of interests underlying my first installation work which I made for the Shanghai Biennale in 2002, “City Boxes”. I made two 1 x 1 m wooden boxes: one represents Beijing; the other, Shanghai. From outside, they are just raw boxes with a peephole. But inside the box for Beijing, I put seventeen models of my favorite old buildings which had been demolished or were scheduled for demolition. Inside the Shanghai box, I began with a famous night photo of the Bund that had been shot in exaggerated perspective with those buildings at the southern end nearest to the camera lens. I then cut the photo and rearranged the buildings in reverse order contrary to their perspectival dimensions, and affixed them to layers of glass, in order to evoke the chaotic and distorted visions the city’s development imposes. I hid all this inside a box that outwardly conveys the impression of a pure, uniform surface.

In The Road Series (2009), photos are the pictures I took through the windshield of a speeding car on nights of mist and rain. These works also reveal a disjunction between their outward form and the real referents of the images. Any overt beauty they might have belies their relation to the disease of Western consumerism that seems to have engulfed China. The Chinese Version is also deceptive in this way. Behind the outward form that recalls Western conceptual art of the 1960s is the tragedy of the missing and the simplified Chinese characters…In my view, a goal of conceptual art was to strip the formal aspect of a work in favor of the idea. My work reinvests a formal aspect that was stripped from Chinese characters by law.

In “ORIENTATION I: Bicycle Tracks”, without an underlying city map, the tracks lose any diagrammatic function. I use my bicycle to make a drawing of something of which I have no clear image in my mind; since my viewpoint, while riding the bicycle, places me in the drawing as I am drawing it. For me, it’s a new way of drawing combined with new technique. On one hand, devoid of its function as a map, the drawing seems to refer only to itself, but in fact, it conceals lots of information: where I went, whom I met, the experience of the city at the speed of a bicycle—even the sort of instinctive urban analysis that comes from my architecture education, my childhood in a Beijing once filled with bicycles—all are concealed in those lines.

As I mentioned, I have been very interested in mathematics since my work on The Chinese Version. I discovered that there is even a class about bicycle mathematics at Cornell University; the rear wheel always tries to follow the front wheel, but they hardly ever track the same line—even though there is a fixed mathematical relation that defines the limits of their potential variations or “discords.” Somehow, it’s like the relationship between partners. But even if it’s been proven, we still can hardly say that theory equals reality. In fact, the representations of the tracks from the GPS recorder app is, in a sense, imaginary since, at each moment, the line is simply the result of a mathematical average between two GPS points each of which has a known margin for error…We cannot say the tracks were really there; we can only say they were almost there. The tension between the reality and imaginary compounds itself in many directions from those abstract lines.

PG: You have stated that you seek to make beautiful art as a means of addressing an atrocious reality. Could you expand on that?

J: In his Ten Lectures on Modern Chinese Fiction, Wang Der-wei, (王德威) (b.1954) considered the reason why the great twentieth-century writer Lu Xun’s (鲁迅) (1881-1936) work contains so many references to beheadings—in Lu Xun’s time, these were commonplace. Wang says that, “on the practical and symbolic level, the state of modern China is a decapitated country, a body severed from the head that is its national spirit. The excitement of its people resides in watching beheadings or in waiting to be beheaded.” The condition Wang ascribes to Lu Xun’s time is perhaps even worse today.

This is the reality that the “beauty” of technological and economic development conceals. If my work seems beautiful, I hope that its outward aspect will generate tension with its underlying themes in ways that draw the viewer to a revelation about the deceptive attraction of beauty. At the same time, I still believe in beauty as a positive value.

PG: You would like to differentiate your work from that of other artists from China. In what ways does it differ?

J: If I tell you my Chinese friends are laughing at me for practicing ballet every day, could you see the difference between the others and myself? I do have some friends who are also fond of traditional Chinese culture like Chinese opera, but they have nothing to do with contemporary art. I think that, in general, most young people in the world feel ashamed to look back at their traditional culture. I don’t understand it at all. I even like folk music. No one in the contemporary art world thinks folk music is cool. Most Chinese artists have an art school education, which I do not have. But I used my time studying to develop other interests. I was forced to read classical literature from the age of twelve. Then I fell in love with it. So I didn’t get any influence from Japanese pop culture like many of my generation did.

Perhaps my installation “Untitled” (2014) marks these kinds of differences. I began with the idea after visiting the Venice Biennale, where I noticed that all the exhibitions tried to have cool titles to catch peoples’ attention, almost like consumer brand names. I then collected around 90,000 art exhibition titles from around the world during the past ten years, and strung them together to make them sound like a continuous narrative, or like rhapsodies; but in fact they are just nonsense; the titles are almost all about the artists themselves. Being an artist does not mean just focusing on oneself, or to be the decoration of a new technology. I would like to keep studying. It’s an adventure for me.

Jia’s most recent and forthcoming exhibitions include:

2015 The Chinese Version, ZKM Museum of Contemporary Art, Karlsruhe (solo exhibition)

2014 You’re Not Supposed to Get It: The Art of Metonymic Narrative, Kühlhaus, Berlin (group exhibition)

2014 Secret Signs, Deichtorhallen, Hamburg (group exhibition)

2014 Untitled, Collegium Hungaricum, Berlin, a performance and installation for Pandamonium, curated by Rachel Rits-Volloch and Fanni Magyar

2013 Maps and Orientation Part 2, Heldart, Berlin (group exhibition)

In a recent biographical statement, Jia writes,

In its underlying critical negation of propositions of recent art history embraced uncritically by the preceding generation of Chinese contemporary artists, Jia’s work, in its conceptual features, often treats ideas originally developed in Western culture such as text-based conceptual art, and the transposition of the readymade to photography in the Düsseldorf School. But in its formal aspect, the work most often reinterprets Chinese paradigms, such as compositional patterns in Chinese calligraphy, and projection systems of the traditional Chinese landscape. This general tension of cultures between the work’s formal and conceptual elements serves a more specific critique of conditions in both China and the West. Most often, the artist chooses for the work an outwardly “pretty” aspect in order to address an atrocious reality.