The Shanghai Biennale: it’s the show we all love to hate. Something about the fact that it’s housed in the Shanghai Art Museum – a hermetic old dinosaur of an institution, with a fossilized website and a fossilized PR department. I have tried several times to get myself on the mailing list, even going there in person, often wondering to myself if it wouldn’t be easier to get on the mailing list of the Pentagon.

Or maybe it’s the schizophrenic program which reads like typical state museum programming – conservative and traditional – with a few shows which look like the artists bought their way in and a few retrospectives which, though important, didn’t really wow us – i.e. Zhang Huan and Fang Lijun.

But occasionally the Shanghai Art Museum (SAM) puts on the mantle of a proper museum and produces a properly researched, well-curated show. Zhang Qing’s “Jelly Generation” for instance helped put a name on a trend in youth art that we had been watching coalesce for some time but had yet to give a name.

Despite its often aloof and stodgy image, SAM was actually quite a vanguard institution in its youth – a platform for avant-garde practice and the site of a number of controversial exhibitions. There was “The Last Supper,” one of China’s first prominent performance art exhibitions, which opened in 1988 and was closed two hours later, a Gilbert and George Exhibition as early as 1993 and Toshio Shimizu’s “SUR-EVERYDAY-LIFE-Seven Japanese Contemporary Artists” in 1998. It was also the site of the first Chinese biennale, which was at the time quite a radical idea. (1)

The Shanghai Biennale, which launched its first edition in 1996, has tended to explore themes of urban life and modernity, says the longtime SAM curator Li Xu, now the director of the Zhangjiang Contemporary Art Museum. “One common part of these themes is attention to urban life,” he says, “All are talking about issues of the city. This was [the director] Xu Jiang who was emphasizing this. It’s not about traditional culture or about countryside culture. Of course different Biennales included these kinds of works but they weren’t the most important.”

The Biennale serves to support official narratives about Shanghai (as a city which is modern and hurtling into the future) and gives a boost to tourism. “Because of the control, they won’t let any critical stuff come out,” says the playwright and art critic Zhao Chuan, “It was just like a postcard. For instance with Fan Di’an [another Biennale curator and director of NAMOC], his shows in Europe had the same problem, they were very clean shows.”

Actually this gets at one of the central problems of the biennale, which is that it’s curation by committee – not that there are a number of curators, but that the decisions of the curators are mediated by the biennale committee. The committee is composed of former curators, SAM staff and leaders of various government cultural organizations including the cultural bureau. “The problem with the biennale,” Zhao Chuan notes, “is that the power of the committee is to large. If the curators want to do something the committee can say no. At the Shanghai biennale, the committee and the director of the committee are very powerful and the result of the whole biennale is that there are some aspects which were the ideas of the committee. There are some that are curator’s ideas. And you don’t know which are the original ideas of the curator and which have been altered by the curators.” (2)

After many years of suffering with this system, Li decided to turn down the offer to curate the biennale in 2006. “It’s not an independent curator stage,” Li says, “I couldn’t realize my ideals. It’s a stage for many other people. It’s not that I can’t cooperate; it’s that I want to express my own ideas. The more a show reflects a curator’s independent spirit, the greater the value it has. I like shows with very narrow themes.” (3)

The First Shanghai Biennale

When it first opened its doors in the 1980s, SAM was referred to as the Shanghai Art Gallery and was more of an exhibition hall, but in 1986, Chairman Fang Zengxian re-launched the museum with a new avant-garde and academic direction. Fang, an acclaimed traditional ink painter, deserves credit for his vision in turning the museum into a platform for contemporary art. To achieve this goal he hired a team of artist curators, Chen Zhen, Yang Hui, Zhou Changjiang, Du Ning and Zhang Jian-jun to advise him on which artists to include in the show. The young artists visited numerous studios, and their findings created much excitement in the art world, nail-biting media and head-shaking officialdom.

Zhang Jian-jun, an artist who has held a number of posts at SAM and was on the biennale committee for a long time, describes the official response to the show: “Then the show opened and the art world talked about it but the leadership wasn’t happy and there was no response from the media. I called one of my friends in the media and they said you were lucky not to get criticized, because there was a lot of famous ‘official’ [socialist realist] art that was not included in the show.” (4)

It’s important to understand that the political climate of that time was vastly different than that of today. Ideas (especially foreign ones) were considered so dangerous that students at the Shanghai Drama College, whose alumni include Ding Yi, Zhang Jian-jun and Cai Guo-qiang, were prevented from using the library.

It was a time when artists painting in unorthodox styles could face writing self-criticisms or worse. Zhang Jian-jun – known for his innovative painting which incorporated mixed media – was demoted from his position as the academic director of SAM to museum doorman all because he had the gall to produce abstract paintings using materials such as porcelain and rock. An interesting side-note is that he then used his position to allow his artist friends free admission to the museum – saving them the five fen (one US penny) admission fee.

In such a climate, even holding a biennale, or any exhibition featuring avant-garde styles, was a radical act. “After 89 most of the art organizations were only doing propaganda work,” says Zhang, “When I came back in 95. [Fang and I] had a meeting, we talked about why don’t we make some national or international exhibitions, to promote some good work? He also made contact with Chen Zhen, and Hu Xiangcheng who had gone to Japan.” Fang eagerly asked his young staff for details on the biennales being held abroad. Figures such as Xu Hong, a female critic who later went to the National Art Museum of China, and Yishu’s Zheng Shengtian were also very influential. Zhang and Zheng with their connections abroad helped not only build bridges with foreign artists and curators but also helped serve as the biennale’s de facto foreign PR department – helping to spread the word of the biennale outside of China.

In fact, since the participation of Chinese artists in Venice in 1993, the idea of the biennale had been in the minds of many artists. Though China participated in Venice as early as the 1950s, when the government sent over some paper cuts, it was Achille Bonita Oliva’s 1993 exhibition of Chinese artists (including Fang Lijun, Yue Minjun, Zhou Chunya and He Duolin) that sparked the debate. Many critiqued Oliva’s selection as “export art” and Zhang Qing, a SAM curator who would later go on to become the deputy director of the museum, positioned the Biennale as a Chinese art show curated by the Chinese. “We confront western cultural centrism,” he wrote, “The ‘discursive power’ of contemporary art, its power to evaluate and to choose is particularly important and prominent. If China did not have the type of internationalized and legalized contemporary art exhibitions exemplified by the Shanghai biennale then the power to evaluate and choose would have remained in the hands of foreign biennale curators.” (5)

Li Xu, another important curator who helped found the first biennale and was very involved in the third and fourth biennales, described it in terms of agency, using the Chinese bei xuanze 被选择 or to “be chosen.” “In international exhibitions,” Li says, “Chinese artists are always ‘being selected.’ This is not very interesting. And every time they choose, it’s often not artists that we think represent Chinese art.” (6)

Still, Li gives credit to Venice for giving hope to Chinese artists that contemporary art could hold such a prominent place in society. Artists at the time likened it to the Oscars and Fang could also see the benefits of the biennale system to the art world.

In a political climate which barely tolerated non-official art, such an event was bound to be closely scrutinized. The team sought to improve their chances by making the first biennale a national biennale which focused mostly on oil painting. “For the first one we couldn’t be international but we chose some Chinese artists from overseas,” Zhang says, “We felt that the oil painting scene was pretty active so we focused on oil painting, with artists from all different provinces. We still had some realistic works because not everyone included could be avant-garde.” (7)

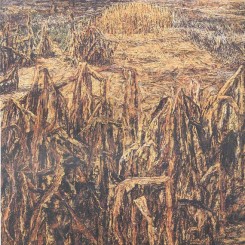

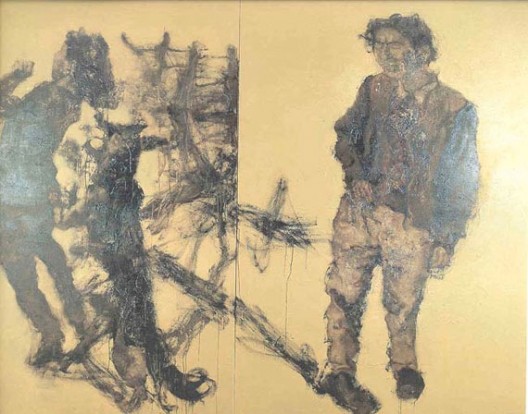

The more “radical” abstract works were interspersed with more sedate works to soften the blow. There were Xu Jiang’s 许江 sunflower paintings (a total rip-off of Anselm Keifer’s sunflowers) and the abstract whitewashed oils of Yu Zhenli 于振立; a painting of a dog attacking a person by Zhou Chunya; a very interesting series of cylindrical paintings by Ye Yongqing 叶永青 featuring deranged humans, wild animals and cages; and Ding Yi’s “Appearances of Crosses” series.

This was mixed in with tamer works such as Qiu Ruimin’s 邱瑞敏 Chen Yifei-esque watertown scenes and a truly horrible realistic work by Luo Zhongli 罗中立 which depicts a cartoony male peasant trying to mount a female peasant from behind. The team also wanted to include Zhang Xiaogang’s family series, but the suggestion was nixed by officials.

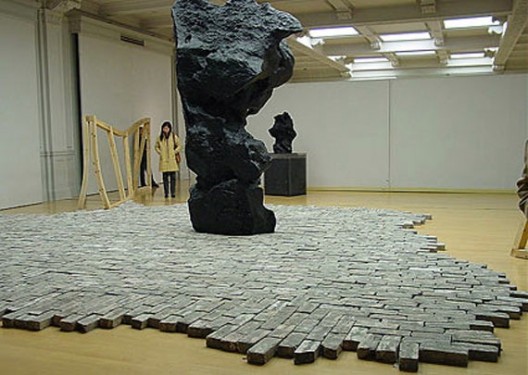

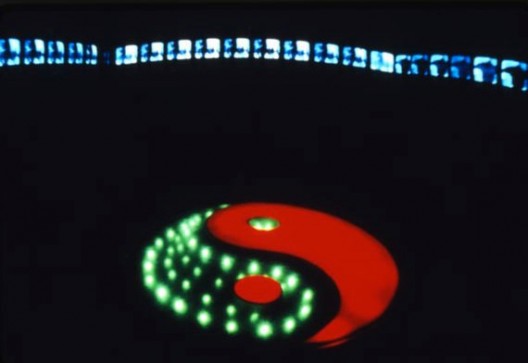

The show even included a number of installation pieces by Zhang Jian-jun and Chen Zhen. Gu Wenda submitted a proposal for one of his hair-based works, but in the end the curators decided the piece was too small and didn’t include it. Zhang Jian-jun produced a piece called “Taichi Disco” (1996) which dealt with the idea of cultural transmutations and the misunderstandings that can sometimes occur. Upon his return to China, Zhang was fascinated by the morning choreography he observed in the parks, “I saw the people dancing disco, and though disco is very free, here they do the same movements, morning and evening. There was another video is of a laowai [foreigner] who was doing taichi. And on the floor I put a thousand bricks from a [demolished] Shikumen – it was not flat, not so stable and the center there was a glass floor with a pattern like taiqi pattern, red and green with lights jumping. Light came up from under the glass floor and on the wall there were 50 old fashioned TVs which were showing people doing military movements but like disco.” (8)

The words “taichi,” an Anglicization of the Mandarin word taiji, and the Chinese word disike 迪斯科, emphasize this element of “lost in translation.” Interestingly, these disike line dancers were dancing to American music such as the Carpenters and not the kind of “synthesizered” Chinese folk and revolutionary songs which often characterize park disike dance parties today.

Being the first video piece to be shown in a museum in China, “Taichi Disco” aroused curiosity from viewers and much disapproval from officials. Zhang’s was not the only work to raise eyebrows. Chen Zhen’s caused a royal ruckus with his installation, which resulted in one of the officials taking his forward out of the biennale catalogue – probably no great loss for the contemporary reader but – but an act that created a political mess for years to come.

Chen’s work, located on the second floor, involved a Mahjong table with 36 holes – an allusion to the thirty-six strategies in Sunzi’s Art of War. When the coins were placed on the table, they could very easily tumble through the holes and into the great maws of chamber pots stationed below the table.

The piece not only referred to an illegal activity (making mockery of the Chinese national sport!) but implied something of corruption, i.e. money dropping into dirty hands, dirty things happening under the table. But most likely though it was the idea of putting a matong or chamber pot in a museum – a symbol of the country’s inadequate plumbing system and backward past – that set off the reaction. Chen Zhen was aware of the inflammatory nature of his work and purposely waited till the evening to install the matongs.

Zhang says that the officials had done a first round pass of the show and suggested that more realistic paintings be added in to dilute the number of abstract paintings. As Zhang recounts: “The museum staff were working hard and were very nervous about how to play politics. That night suddenly one of the high-ranking officials came to go over the show. Suddenly he saw Chen Zhen’s work and he said, ‘Remove this work. You lied to me.’ Apparently he thought that the work hadn’t been included in the proposal but the staff confirmed later that it had and had just been overlooked.”

This set off a mad scramble to find Chen Zhen, who was understandably quite annoyed. He worked out a compromise with the museum staff to remove the chamber pots and place Vaseline on the surface of the table – an effect which no doubt must have conveyed a tangible sense of slickness and greased palms. The coins were replaced with poker chips; since the renminbi coins bore the national seal and were deemed unfit for such commentary.

Titled “Kaifang de Kongjian,” or “Open Space,” the first biennale did represent a platform for new forms and ideas, despite official interference. The opening day, which should have been a somewhat raucous occasion, was actually fairly stiff and formal. (Even to this day we still try to go late enough to avoid the talking heads.) “I walked in and saw these girls in qipaos, with red ribbons across their chests, like a grand opening for a hotel or a shopping mall,” says Zhang, “In the US we never see this and I thought, ‘Wow, what’s this?!’ Of course I know the leaders, they were quite nervous because they didn’t know what would happen, and they were so relieved. So many people came for the opening.”

Still the media were hushed and the museum had to write a self criticism.

Later Biennales

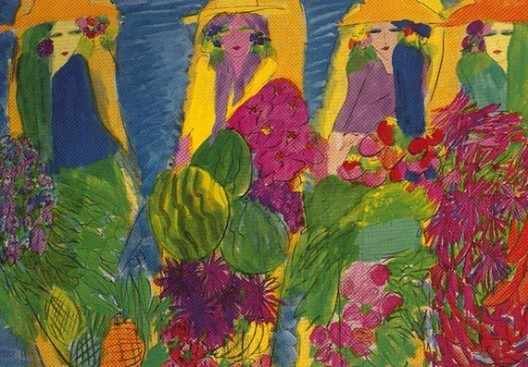

In the second biennale, Fang decided to go for a safer topic – focusing on his specialty of ink painting – to give everyone some time to cool off. The second exhibition, the awkwardly titled “Inheritance and Exploration,” was divided into two parts with the more traditional work being housed at SAM and the abstract ink work being shown at Liu Haisu Museum in the suburbs. Besides some shlocky “native soil” type painting by artists such as Zhao Qi 赵奇 and tropical rainbow portraits of women with flowers in their hair by Ding Xiongquan 丁雄泉, the exhibition displayed some very stunning ink work by Wang Tiande 王天德, Zeng Zuohe 曾佐和 and Shi Dawei 施大畏.

The show was also followed by a three-day conference on ink painting where international scholars debated the possibilities for new ink paintings. This show unsurprisingly drew little controversy, but some in the art community criticized the Biennale’s failure to internationalize.

By the time the third biennale rolled around, organizers had mustered the courage and the resources to make it an international cooperation. The Japanese curator Toshio Shimizu participated, along with Hou Hanru, whose experience in France made him more international. The selection of artists also included a number of big names (William Kentridge, Mariko Mori, Mathew Barney), something which was part of the strategy of the organizers who hoped big names would attract media support and win over the government.

The third biennale was seen by a number of observers as a real breakthrough in terms of Chinese contemporary art, whereas the previous two were more like trial runs in order to facilitate a level of comfort with the concept of foreigners and Chinese working together to create a contemporary art exhibition in a highly visible public space.

Though the curators all knew each other (Li and Hou had both gone to the Central Academy of Art), and Li knew Shimizu through his exhibition at SAM earlier that year, the collaboration between the three was often less than harmonious. Li accuses Hou of wanting to put himself at center stage and make decisions without first running them by Fang and clearing them with the museum.

The third Biennale was also the first biennale to really attract the attention of the international community. Barney’s “Cremaster Cycle 5” was shown at a local cinema, and Anselm Keifer, who has had a momentous impact on Chinese painting, helped bring in media attention.

By far the standout piece of the exhibition however was Huang Yongping’s “Bank of Sand,” a version of the HSBC bank building on the Bund. The piece was made out of cement mixed with sand and conveyed this idea of the washing away of colonial power and crumbling empires as the piece actually fell apart during the biennale.

The biennale also sparked off a number of satellite shows; Zhang Jian-jun estimates that there were twenty to thirty exhibition openings – a record number for that time. There was also the legendary “Fuck-Off” or “Uncooperative Approach” which certainly garnered a lot of attention, but the biennale curators were forbidden from visiting for fear of being seen as instigators or promoters of uncooperative approaches. This is why SAM has been very discouraging of the use of the term “satellite show” and the use of the word biennale (Shanghai MoCA was asked not to use the word “biennale” in the title of their shows); indeed, in 2002, the Shanghai Biennale Committee also posted a legal declaration in major newspapers in an attempt to suppress any “external exhibitions,” as Zhao Chuan writes. (9)

“Fuck Off” caused such a huge fuss that it was used by critics of the biennale (mostly artists painting in more traditional styles who were therefore excluded from the biennale) as ammunition against the biennale concept. These fuddy-duddies passed the word up to Beijing and for a time it was unsure whether the next biennale would come to pass. “I went to Beijing and took a lot of opinions and collected them into a report,” Li Xu says, “I collected opinions from the propaganda bureau and the officials, from the general public, from the media, and the people from outside the art world. We did a big survey and officials finally said, ‘Okay, it’s confirmed.’”

This was considered a big moment for the avant-garde. The critic Zhu Qingsheng writes how he previously made a public point of not criticizing contemporary art because it “did not even have the right to exist.” And indeed, with the Biennale’s pitched battle with the media, negative voices may have been detrimental to its survival.

Zhu Qingsheng writes: “‘Legitimized’ means something that is normal and public. However this does not mean that all experiments in modern art can be carried out publicly after the Shanghai Biennales or that all modern artists can gain social recognition. Not at all! It simply means that from here on out modern art is no longer illegal or a ‘crime.’ It will no longer be denounced or protested against or refuted in the public media. It will no longer stand for the objectionable practices of museum not displaying installation art and it will no longer appease the magazines that slander modern art.” (10)

Zhao Chuan has also written about how the biennale’s internationalism and its potential to bestow “face” upon Shanghai was actually what won the support of the government: “This became a turning point, as the Shanghai municipal government was determined to demonstrate their open-mindedness and desire for progress like that of the West. Consequently, as the progressive art movement in China steered towards a course promoted by the Western contemporary art world, its imported influence was positively received. Though the Jiang Zemin administration’s utilitarian mindset was not ready to accommodate any radical art forms, it nonetheless was also aware of the profits that could be attained by supporting and presenting this style of contemporary culture given the potential for attention and investment by the West.”

So with government support behind it, the biennale charged into 2002, this time with a gaggle of foreign curators like Alanna Heiss, Klaus Biesenbach and Yuko Hasegawa.

This show was a real exercise in cross-cultural communication. Li Xu was given briefs on which artists would be chosen but often he had to work out the details of the various projects with the artists over email getting up in the morning to correspond with the Chinese artists, talking to the European artists in the afternoon and the North American Artists at night. Sometimes communications went awry as in the case of the collective Gelatin. “They were really naughty,” says Li, “They told us their plan and then changed it. They did some really bad things like pretending to be disabled people and driving the museums wheelchairs around the building and then they saw everyone in Shanghai wearing pajamas and so they bought the most colorful pajamas and started wearing them in the street (and making a ruckus).”

The group actually said that their first proposal was cancelled by the curators and so they showed up in Shanghai with a bag of tools, and then proceeded to construct a slum on the lawn of the museum made out of waste materials generated by the biennale installation – which resulted in a fairly interesting work in the end.

The Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist was also invited to make an installation using projectors, colored lights and music in the director’s office on the top floor, but when she arrived at Pudong Airport, Li Xu was called by immigration officials. Li Xu recounts this incident: “They asked, ‘Did you invite her to participate in this exhibition?’ I said, ‘Yes, why?’ and the official said they’re planning to put her on the next plane to Switzerland. I said Arghhhh! No Way. I talked to them for half an hour and they said, ‘The great gate of our country doesn’t let just anyone in. We have rules.’ I then asked if he could think of a way? They asked me, ‘Can you give us proof? What is the government body which overseas you?’ And I answered ‘the Cultural bureau.’ He said the Cultural Bureau was too small, “go up another level.” I said Shanghai Municipal Propaganda Bureau and he asked me to get them to give me a chop. I cried, “Aiyo! It’s 8 pm on a Sunday! How am I going to find someone?” Then I told them I had the museum’s chop. ‘Will you be able to let her in?’ I asked. He said, ‘Send me a fax within 20 minutes.’ When she arrived at the museum, she said, ‘Li Xu, I am so stupid!’ I said, ‘Don’t worry.’” (11)

Li also had some interesting experiences working with Yona Friedman. The elderly artist didn’t use email; every time he needed to communicate with Li, he would write out his ideas in a lovely cursive and send them to Li by fax.

“When Friedman was here I found a very young female student to be his assistant and help him install his work. Her name was Gong Yan and she worked on [the magazine] Yishu Shijie. Her father was a very important leader who was against the first biennale because he didn’t like Zhang Xiaogang and Chen Zhen. Her father thought it was not suitable for the time, but in the fourth biennale she came to be volunteer. This is how things change.”

Li marvels at the ability of audiences and their abilities to accept new mediums. From frowning at abstract painting to being able to sit through hour-long videos in the space of a decade is pretty impressive. “It’s about Shanghai’s history of having a foreign influence,” Li says, “There is a proverb ‘jian guai bu guai,’ meaning not to see strange things as strange, because in Shanghai all manner of strange things occurred fifty or sixty years ago. The city was a very avant-garde place then, and even up to now we still haven’t caught up to that position. We need to be more pluralistic and open, to allow people to develop the things that they find interesting and not to say ‘I don’t like this so it shouldn’t happen, that would be really be harmonious.’ (12) The characters for ‘harmonious’ hexie in Chinese are 和谐. The first character is ‘he’ which has a radical for ‘grain’ and the sign for ‘mouth’, so everyone has rice to eat. ‘Xie’ has the radical for ‘language’ with the radical ‘jie’ which means ‘everyone.’ So [‘harmonious’ means] everyone has rice to eat and words to say.”

It’s a very valid point, and here Li Xu puts his finger on why the Biennale has yet to achieve its full potential. Instead of being a showcase for Shanghai the city, it needs to be a showcase for the art scene, as an opportunity to show the world how tolerant, open and cutting edge we are.

Footnotes

(1) The Guangzhou Biennale, which was held in 92, was technically earlier, but since there was no second Biennale, we can’t really count it as an ongoing event.

(2) From an interview conducted by the author in October 2010.

(3) From an interview conducted by the author in October 2010.

(4) From an interview conducted by the author in October 2010.

(5) “Transcending the Left and Right: The Shanghai Biennale amid Transitions 2000,” Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents, Wu Hung, The Museum of Modern Art: New York 2010.

(6) Even though artists were not choosing themselves, they knew that in working with Chinese curators, the penchant for “exoticism” be it communist or ancient Chinese was likely to be minimized.

(7) From an interview conducted by the author in October 2010.

(8) From an interview conducted by the author in October 2010.

(9) “Fuck Off: An Uncooperative Approach,” Zhao Chuan, Broadsheet Magazine: Adelaide 2008.

(10) “China’s First Legitimate Modern Art Exhibition: The 2000 Shanghai Biennale” by Zhu Qingsheng 2002-03, Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents, Wu Hung, The Museum of Modern Art: New York 2010.

(12) From an interview conducted by the author in October 2010.

(13) I.e. as in the policy of “Harmonious Society.”