“Attached”: group show with Lee Donsoon, Han Ho, Tao Na, Yan Kai, Tan Tian

Force Gallery (798 art district, Chaoyang, Beijing) March 8–April 22, 2014

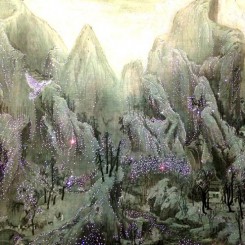

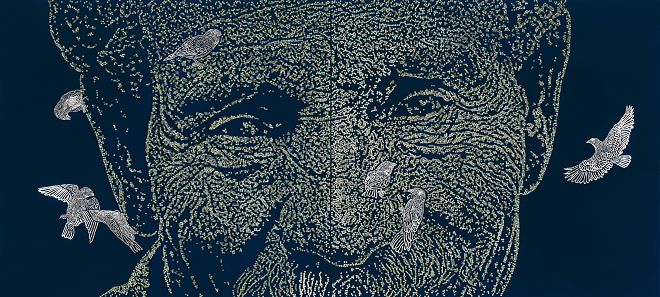

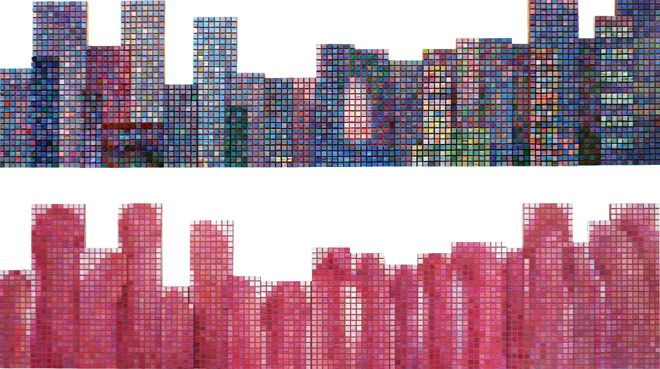

Exhibitions at Force Gallery are always a meeting of Chinese and Korean artists, and the current show is no exception. Entitled “Attached,” all of the works featured have different “supplements” attached to their surfaces. For example, Tao Na’s “Sex and the City” comprises two layered images composed of ten thousand “paint chips” covered in magnetic paint—the top layer of multicolored pieces of paint creates a mosaic effect, which gives the impression of a vibrant cityscape lighting up at dusk. Viewers can move and remove these magnetic paint chips at will, or even slip a few into their pockets. This gradual process of erosion eventually reveals the layer of images hidden beneath the first—a grouping of male genitalia, a reference to the lust hidden beneath a bustling metropolitan façade. In contrast, the Korean artist Lee Donsoon’s work possesses a greater sense of refinement. By hammering innumerable nails onto large wooden boards and spray painting the nail heads, the artist has formed different images which speak a similar visual language to woodblock prints, creating a beautiful effect that is testament to the large amount of manual labor involved in the process of creation. Han Ho, another Korean artist, has chosen to modify a landscape by a Tang Dynasty artist, Li Zhaodao, called “Emperor Going to Shu”. In “Eternal Light — Lost Paradise”, Han Ho inserts several female nudes into Li Zhaodao’s famous landscape. In comparison with Hong Hao’s Elegant Gathering series, Han Ho’s methods are subtler. Additionally, the artist has made small perforations in the edges of the mountains and installed LED lights behind the canvas. When the lights are turned on in the evenings, the piece is all the more dazzling.

Clearly, the artists have adhered to the exhibition’s theme of “attachment”. All of their pieces also emphasize workmanship; the intricate labor involved brings their work to a higher level of exquisite detail. However, there are a few essential differences between the works by the Chinese and Korean artists in this exhibition. The Chinese works comprise clearly layered thematic elements and intent, much in the same way that “Sex and the City” is formed of two layers of images. In other words, audiences who experience the Chinese artists’ pieces can easily fill in the blanks to the sentence: “the piece expresses _____ through the use of _______.” On the other hand, the Korean artists’ works here are different, since on the surface, perhaps, they lack any obvious “deeper meaning or intent” and are therefore more susceptible to being censured—especially by a number of Chinese viewers who have the habit of interpreting contemporary art under the framework of specific concepts.

Tao Na, “City of Desire 1”, 320 cm x 215 cm, ten thousand magnets, paint, PVC, 2009

陶娜,《欲望都市1》, 320 cm x 215 cm, 1万片磁铁、颜料、PVC, 2009

An ordinary Chinese viewer will probably find it difficult to find political, social or moral implications in the works of the Korean artists in this show—and not even any traces of the “reflection on tradition” all too easily found in so many Chinese artists. With the continual influx of Western art, the 1988 Seoul Olympics, Korea’s economic ascent and its rapid urbanization and development, perhaps “traditional paintings” (as they were) have entered a relative decline. In contrast, perhaps in no other country has traditional culture been rendered into mere symbols as precipitately as in China. Just like the Chinese courtyard houses (siheyuan), the Korean hanoks (traditional buildings) have also moved aside for high-rises; similarly, Korean art has aptly manifested the new visual experiences brought about by urbanization.

This is not to say, however, that there has been no political art in Korea. In fact, the May 18th Democratic Uprising (the Gwangju Uprising), when students and workers rose up against the government in 1980, further stimulated the development of Minjung Art (People’s Art)(akin to China’s Political Pop). But without the aid of a “Cold War” mentality, the “folk art” movement faded out much earlier than did China’s Political Pop. Like traditional ink painting, traces of political art still linger in Korea. However, the Korean paradigm is very different from China’s because political art is relatively marginalized—even to the point of being cast as “Leftist art”, by one Korean gallerist. Thus, when Chinese viewers see contemporary Korean art, it is easy for them to fall into the habit of leaning too far to the “left” or the “right”. They might fail to find in the works any moral or political critical consciousness which they have come to expect, nor any familiar sense of “historical and cultural heritage” (though historical and cultural, “Emperor Going to Shu” is merely the backdrop to Han Ho’s work, and not a product of his own intent). Very possibly, the perceived emptiness and superficiality of Korean art under such a reading in China is due far more to the Chinese tendency to “overload” ourselves with concepts and preconceptions.

(The article has been emended since publication in accordance to the writer’s wishes.)