by Julie Chun

“Yangjiang Group: Fuck Off The Rules”

Minsheng Art Museum (Bldg F, No. 570 West Huaihai Road, Changning, Shanghai, China) Nov 08, 2013–Feb 22, 2014

The anarchic title of Yangjiang Group’s show at Minsheng Art Museum obliquely echoes the subversive overtones of Eastlink Gallery’s notorious Fuck Off exhibition instigated by Feng Boyi and Ai Weiwei. Back in 2000, the title had to be diluted, and was loosely translated as the “Uncooperative Attitude.” While not as radical in scope or production as the historical show, Yangjiang Group’s stance remains just as resolute in their obdurate disregard for artistic as well as social mandates.

The group’s name is derived from three artists—the hard-drinking, chain-smoking inhabitants of the blue-collar industrial city of Yangjiang in southwestern Guangdong Province. Fluctuating between states of under-the-influence and sobriety, Zheng Guogu, Sun Qingling, and Chen Zaiyan have managed to work together for over eleven years. Their artistic practice is an in-your-face challenge to the venerated culture of calligraphy and its governing rules. In fact, they can’t even recall what the rules are.

It is this disregard for convention that permeates the group’s solo exhibition curated by Li Feng, which highlights a pastiche of nine works previously showcased at domestic and international venues. The site-specific “Morning After: Masterpieces Written While Drunk” casts aside all rules of disengagement by conflating the sophisticated art of tea-tasting and Chinese chess with the baser social games of binge drinking and sugar cane splitting (performed by local street vendors for the purpose of selling the sugary juice.) “Pine Garden—As Fierce as a Tiger Today,” originally shown in 2010 at Tang Contemporary in Beijing, has been re-articulated in one of the main galleries, complete with artificial plantain groves and an obstructed river composed of degenerate calligraphic works that quiver in an impotent gesture. The contesting elements serve to intervene in an expansive bamboo grove—a seemingly tranquil yet distinctly fabricated space resonating with plastic tropical plants, a cascading waterfall frozen in wax and lyrics of traditional Cantonese music sung by Zheng Guogu’s father. Despite an atmosphere of disjuncture, the site is eerily familiar for those who have been to Guangdong.

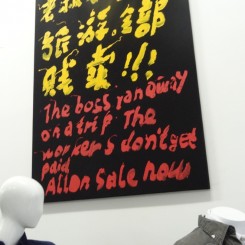

Yangjiang Group, “Final Day, Final Fight”, mixed media and process, 2010

阳江组,《最后一日,最后一搏》,综合材料与过程,2010

The show abounds with interactive installations that unwittingly suck the viewer into their vortex. In “Final Day, Final Fight” (2007), an entire gallery has been converted into a makeshift clothing store, complete with dressing rooms that portend its “going out of business.” Most of the articles of clothing carry small patches of comical yet disconcerting epigrams that mirror the ostentatious signs on the walls. “Wife ran away/ Taking all belongings,” and “Expropriation/ Difficult business/ Suicide after sale.” All items are literally available for sale, and the viewers are invited to partake in the familiar ritual of shopping. Rummaging through the racks, one can try on clothes and walk out of the museum with a purchase. Notwithstanding the signatures of the three artists loudly emblazoned on the clothes, the painterly slashes on the apparel suggest the paradoxical notion of damaged goods, thus reinforcing the theme of devaluation and bankruptcy.

“Are You Going to Enjoy Calligraphy or Measure Your Blood Pressure?” (2007) seeks to quantify the qualified art of calligraphy, but only under the group’s terms. Surrounding the walls on four sides are large panels of calligraphy that were erratically scrawled in a state of drunken stupor; most of the canvases are illegible. In the middle of the room, on a table, a small blood pressure measuring device and a recording log is provided. The viewer is encouraged to take a pre and post reading after viewing the panels. The premise supposes that contemplation of calligraphy produces tranquility and lowers one’s blood pressure. Yet the installation also explores the other side of the equation—that creation of calligraphy without formal restrictions can be just as emancipating. Subsequently, the group’s practice echoes the gestural liberties taken by the ancient literati. As the sages had gathered to drink plum wine, compose poetry and paint, they were able to throw the court-sanctioned rules to the wind. This piece reinforces the interventionist endeavor thus provoking a moment of clarity, which seeks to re-examine the production and reception of the art of calligraphy.

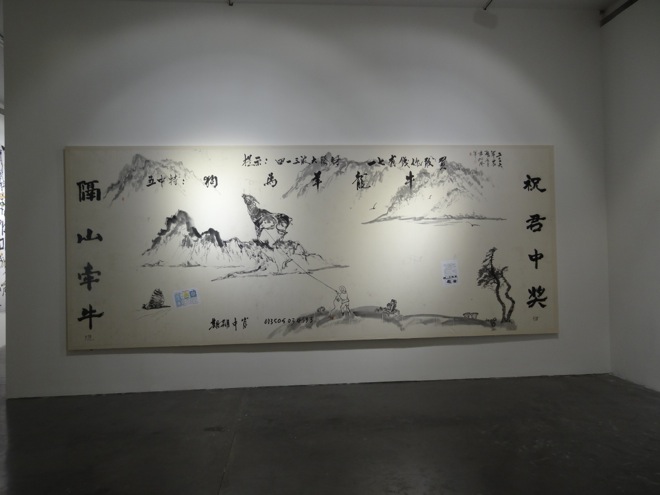

While many aspects of Yangjiang Group’s show are distinctly rule-breaking, it is “Mouse, cow, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake” from 2006 which delivers the penultimate message. On the surface, the installation is a pictorial reference to the gambling culture that is a fiber of local Guangdong life. Large expanses of calligraphic scrolls are splashed with irreverent lines and indecipherable scripts, thus denigrating the traditional art form to street graffiti. The surfaces are further littered with pieces of gambling stubs randomly plastered throughout. In the midst of this profusion of visual chaos, two tiny video monitors are mounted on a wall where the viewer can voyeuristically observe the artists and their family and friends partaking a casual meal in the close confines of a kitchen. Amid the clamor of people coming and going and the clanging of dishes, there is an ensuing stream of conversation surrounding the business of gambling. This seemingly mundane and ubiquitous ritual reflects the complex polemics inherent in the vernacular culture of Guangdong residents’ lived reality.

Despite their global fame, the artistic practice of the Yangjiang Group remains resolutely local, down to the last uttered syllable. They refuse to move from their oddly constructed studio on the outskirts of Guangzhou to the bigger artistic centers of Beijing or Shanghai as many of their artistic colleagues have done. Call it proud, call it stubborn—say what you will, they will not be persuaded otherwise. They have been invited to exhibit at Birmingham, Lyon, Stockholm and San Diego, and whether sober or drunk, they always manage to find their way back to Yangjiang. Perhaps it is this deference of eschewing artistically accepted rules that have allowed this eclectic and eccentric three-man group to emerge victorious as winners in their self-constructed game of art. While Beijing and Shanghai may stand as the geographical centers of artistic influence, artists such as the Yangjiang Group are successfully asserting their peripheral locale as the site of critical consideration. As such, they are able to deliver quotidian expressions as a relevant and alternate discourse with engaging wit and thoughtful provocation.

Yangjiang Group, “Mouse, Cow, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake”, mixed media and process, 2006

阳江组,《鼠牛虎兔龙蛇》,综合材料与过程,2006