This review is included in Ran Dian’s print magazine, issue 3 (Spring 2016)

“Datong Dazhang”, solo exhibition (organized by the Power Station of Art and the Wen Pulin Archive of Chinese Avant-Garde Art)

Power Station of Art, Shanghai (200 Huayuangang Road, Huangpu District, Shanghai) Dec 30, 2015–April 10, 2016

As a tall man hailing from Datong in Shanxi province, Zhang Shengquan had, in the customary Chinese manner, the nickname of “Da Zhang” (lit. “Big Zhang”), and thus ended up being known as “Datong Dazhang”. He started making art in the 1980s. After seeing the “New York Contemporary Painting” exhibition in 1987, he determined that his artistic pursuits lay in the unaware, the now, and the momentary; he organized the WR Group, which began to gain attention in 1989 for their performance “Mourning (Three Men in White)” at the seminal “China/Avant-Garde” exhibition in Beijing. In 1993, he created a periodical called The Right Guard, which involved mailing manuscripts of artistic proposals to people in the scene. In 1996, he was invited to take part in an exhibition with his work “Crossing”—for the first and only time. On New Year’s Day in 2000, he hung himself in his apartment in Datong, abandoning his own life as his last art performance (in the words of the critic Li Xianting). The current exhibition (curated by Xiang Liping and Zang Honghua) at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai is his first museum solo.

Without a doubt, Datong Dazhang strived hard to make breakthroughs. From his letters to his friend Zhang Lei, a few things can be noted: 1) he read widely from philosophers still quoted today—the likes of Foucault, Derrida, Nietzsche, Kant; 2) He had a deep understanding of mediums and language—be it the boundaries of language or reliance on the medium of language; 3) He interacted with the art scene with ease—he absolutely was not withdrawn like the “King of Kowloon,” for instance. In his letters, he analyzed Gao Minglu’s mentality, mentioned Ai Weiwei paging him, and included names like Li Xianting, Song Dong, Dai Yuguang, and others; 4) He consummately quoted from the Black Cover Book and China Art Weekly [Meishubao], and his letters mentioned how he had the entire set of Jiangsu Pictorial. It can therefore be deduced that Dazhang’s thought process was filtered highly through the media. From this I can imagine him as an “art youth” living in the sorts of second or third-tier cities that rely on intellectual sustenance from magazines and the media to shore up their ideals and resist philistinism in the outside world. They struggle left and right, hoping to find a more appropriate way out in life in general. The vast majority compromise and find an ordinary job in the “food chain” elsewhere—after all, the art world can only take in so many people; also, there was no real “art industry” in China then. Even the minority who persisted were incorporated in the official “institution of art” [yishu tizhi] to a great extent because they strived so hard just to reach the positions they hold today—official posts in museums, art academies, and cultural heritage work units [danwei].

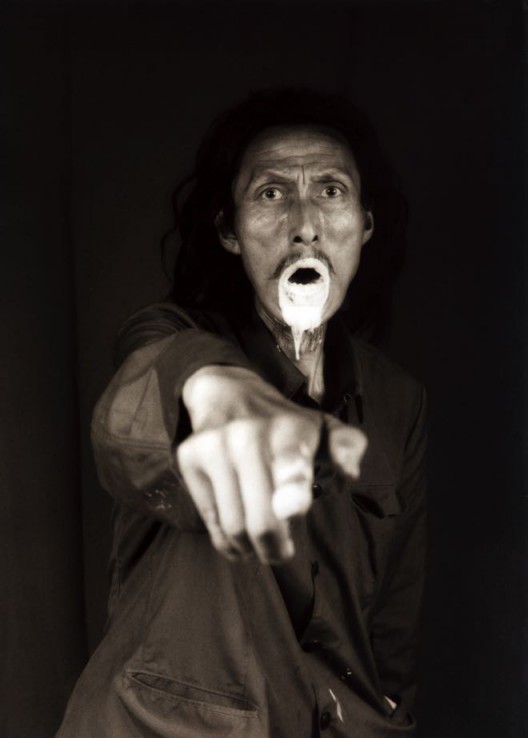

大同大张,《WR 90宣言》(图片由上海当代艺术博物馆提供)

Datong Dazhang, “WR 90 Manifesto” (courtesy Power Station of Art, Shanghai)

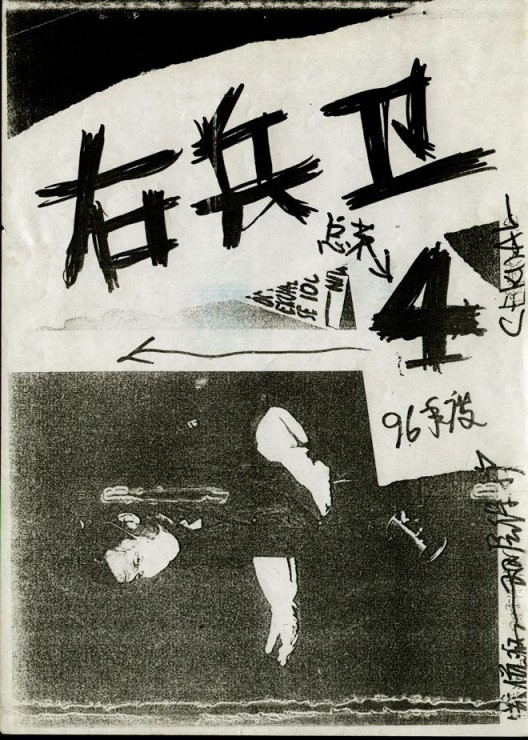

大同大张,《渡》,行为图片,1996(图片由上海当代艺术博物馆提供)

Datong Dazhang, “Crossing”, photographs from the performance, 1996 (courtesy Power Station of Art, Shanghai)

As a relatively young “art youth” [wenyi qingnian] myself, coming from a family working in a second or third-tier city banking system (which back then was state-run, not private), I could not help but smile at Dazhang’s résumé. Eight or nine guests out of ten at home would be people like this: some did music, or photography, or else wrote poetry and songs, and more did painting. Gathering at home to discuss “major issues,” everyone would become excited, quaking intellectually without restraint, always plotting to do this or that and getting all worked up about philosophy. You would feel the energy gushing forth from them. Never having seen Red Guards, I would always associate them with some great “Red Trailblazer.” In these government work-units [danwei] with relatively generous benefits, interpersonal relations were never as tense as they proved to be in private or foreign enterprises later on; some leaders of these work units would even display pride if their danwei produced an artist. From the artists’ perspective, many did attain a certain rank (the vast majority of the “Misty Poets,” for instance, had official posts)—only that back then there was no real “tertiary” or “service” sector, nor was there any space for survival outside the official system. These danwei were where idealistic artistic youth had the best chance of belonging.

In China, however, centralization is ubiquitous; even heterodoxy is concentrated in the center. Only through state-to-state modes of relations and exchange could many foreign ideas legitimately appear in “the center,” without any practical chance of truly penetrating the regions. Deprived of these opportunities for [international] exchange and interaction, artistically and literarily inclined youth naturally fretted; yet this brooding could very easily become a force that intensified the internalization of the institutional system. If official artists did two works with buttocks showing, then I would do ten. You can paint realistically? I would make mine even more lifelike. Your paintings are painted thick and heavy? I can paint mine darker and thicker. Such a competitive order enveloping art exhibitions and the media could easily reach extreme levels among “regional artists.” To this day, brawling over “[moral] character,” or over [being] “low-key,” “hoodlum” [liumang], or “crude” are recurring themes in the Chinese art scene.

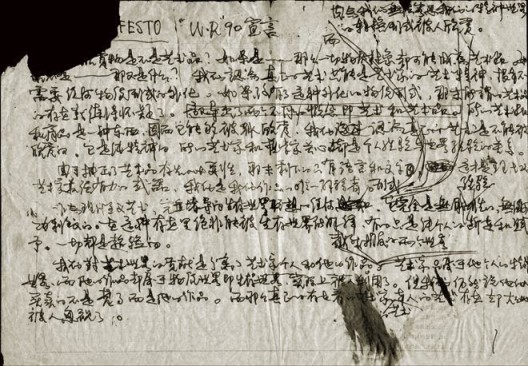

大同大张(张盛泉),《右兵卫》封面,1996(图片由上海当代艺术博物馆提供)

Datong Dazhang (Zhang Shengquan), cover of The Right Guard, 1996 (courtesy Power Station of Art, Shanghai)

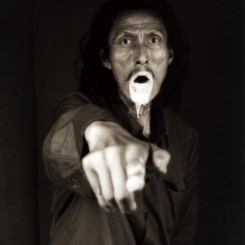

大同大张,《煤场行为1》,行为图片,1995–1996(图片由上海当代艺术博物馆提供)

Datong Dazhang, “Act in the Coal Yard”, photographs from the performance, 1996 (courtesy Power Station of Art, Shanghai)

For a small-town youngster who had never decided whether he would do literature, music, or painting, that Dazhang’s early abstract paintings (heavily influenced by de Kooning) could stand out and display great confidence was an immense accomplishment. In his later period, in the 1990s, he collected a large number of drafts for large-scale installations and performances in his “Mail Art” publication The Right Guard. Even though this mail art didn’t go far, Dazhang was very clearly aware of his own marginal position, and this act of “breaking out” was nonetheless effective for him. The drafts included some already-executed works, like his best-known work “Crossing”, where he carried a sheep across a river and then would have killed and sacrificed it (had Song Dong not intervened); in the series Act in the Coal Yard in a Shanxi coal yard which no one visited, there is an intensely romantic quality and ritualism. As a Christian maxim [through Blaise Pascal] has it: “Kneel down, and you will believe!” Li Xianting summarizes this highly ritualistic bodily experience of kneeling as the “experience of survival,” which seems to overstate the case, since the socially created structures and order have long been naturalized internally out of each encounter with lived-in reality.

Yet artists in the ’85 New Wave Movement all sought such bodily rituals—which to a great extent magnify psychological processes of suggestion, thereby also magnifying the artistic ideals of (small-town) youths. Whether in Yuanmingyuan performance art or the artistic modes of the Beijing East Village, the technique of ritualization was to have arisen in response to Robert Rauschenberg’s influential 1986 exhibition in China—even if Rauschenberg himself merely painted using other forms. Taking it a step further, once ritualization was stripped bare, so to speak—with pieces that involved the scandal of cannibalism (Zhu Yu in 2000), draping white shrouds (WR Group’s “Mourning (Three Men in White)” in 1989), hanging a red carpet (Datong Dazhang’s “Act in the Coal Yard” in 1995–1996), the “Little Red Figures” (Lu Shengzhong since the mid-80s, inspired by the folk sorcery practice of “hitting the villain”)—it enabled performance art to be distinguished from the everyday living environment. A sense of ritual affirmed the artists’ sense that they were “doing art” and legitimated their existence within this environment. The way they understood art—with details standing in for something of greater symbolic significance—could be connected to the legacies of folk sorcery and the votive practices of ancestor and spirit worship as passed down in Chinese tradition. This mode can clearly be offset against performance art in China today—for example Li Binyuan’s tactics of infiltration, pumping tires in public or brushing his teeth in the subway.

Rituals intensified the autonomy of art and its freedom, and slid towards a nihilistic romantic utopianism which in turn intensified ideological control. The role of ritual in mass psychological suggestion is the one and only function of art that many scholars are prepared to affirm: art as a means to apprehend the world, as proposed by Feuerbach and adopted by Marx, Mao’s ideas on “imagistic thinking” (xingxiang siwei), and even Bourdieu’s simple attribution of art to symbolic capital—all of these are really no different on some level. Allan Kaprow’s mode of “plan+improvisation” was critiqued because the level of the “plan” had too much ritualistic content and that inextricable symbolic romanticism. The many Fluxus works which demanded a stage stem from the same origin. Today, many performances have become “clown shows” at openings, completely at odds with performance art’s original intent. “Artists” have started to emphasize the technique of “performance,” which really amounts to their genuflection before the ossifying “institution” of performance art.

Transforming ritual into everyday action is not easy. Be it Hannah Arendt’s attempt to jolt the bookishness of New York intellectuals with her post-war “Theory of Action” or that rough-and-tumble “code of honor” (jianghuqi) that the Beijing exhibition “Unlived by What Is Seen” last year could not shake off, ritual symbols are stymied from being transformed into real action that produces real results. Walter Benjamin, when analyzing the mechanical reproduction of art in 1936, stops here, at a point which can only be a third-rate philosophy of technology (in Chinese, this would be termed a dialectics of nature). What he really wanted to say was that by bearing out this non-auratic reproduction of art, he had deduced that art is already politics itself.

The most pressing issue for art as politics is not ritual or symbols, but linking up with related mechanisms of mobilization. I once asked Gao Minglu why the ’85 New Wave Movement, as an art movement that brought together and mobilized a group of people, was so easily overturned. Right from the start, the ’85 New Wave Movement moved strangely towards “artistic autonomy” and the “freedom of art”; this perhaps stemmed from a backlash against the Cultural Revolution as supported by the political center—a belief that the Cultural Revolution robbed them of freedom that they wanted to demand back. This, instead of pushing forward from the basis of Mao Zedong’s “rustication of intellectuals” and “Cultural Revolution” to establish a more careful, circumspect relationship between intellectuals and the blind collective action of the masses, in order to create an institutional system that would interact and communicate with the “silent majority.” Only when there is a conversation with the masses can there be a basis for mobilization.