Separation—Zhu Yu Solo Exhibition

Long March Space (Jiuxianqiao Road, Chaoyang District, 798 Art District, Beijing 100015), March 7–May 24. 2015

Sometimes, taking the extreme route is taking a shortcut. At other times, no reason is needed; extreme behavior can be dictated by irrational, emotional influences: utter despair when all hopes are dashed, tears of joy, a dip into extreme grief following a moment of profound happiness. But if a person who has always tended toward extremes exhibits an unusually mild side, their new choice still appears somewhat extreme: the extreme of non-extremes!

On the first day of 2000, the performance artist Zhang Shengquan of Datong, Shanxi ended his life in suicide, becoming the most extreme of extreme artists. By sheer radicality, he had beaten other artists like He Yunchang, Zhang Huan, Peng Yu, and Zhu Yu. In an age in which the logic of the “simulacrum” had not yet truly penetrated Chinese culture and the myth of originality was worshipped and revered, Zhang Shengquan wrote on the wall of his own bedroom, “The endpoint of art is the question of whether or not to go on living. Because the moment any one of an artist’s discoveries is used, whether by others or by the artist himself, it loses its meaning.” Zhu Yu might not agree with this statement. After having fallen silent for a long time, he now exhibits paintings which, for the most part, are comprised of clean, delicate surfaces—though the dining plates with outlines of vaguely identifiable human organs tell an older story….

Zhu Yu’s wide renown comes partly from his bloody “Post-Sense Sensibility” exhibition of 1999, and even more so from other series of works that made spectators bristle with anger. These include “Sacrifice: Feed a Dog with His Child” (2002) (in which he fed a four-month old fetus he had conceived with a prostitute to a dog), “Eating People” (2000) (photographs, exhibited in the “Fuck Off Exhibition,” of the artist cooking and eating a human fetus), and so on. Although the powers that be later came out with laws forbidding the exhibition of such gory performance art, the shift Zhu Yu, Qiu Zhijie and others took in their practices was not necessarily because of this new policy (and He Yunchang did not stop at all), but rather because they began to feel that the discourse of body politics was no longer current.

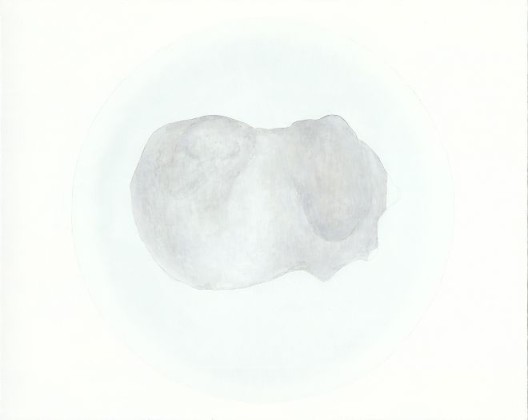

In the present exhibition, on kitchen dishes, Zhu Yu shows us patterns that bear resemblance to human organs steeped in tea at the same time as indicating spruce firs, or Taihu rocks, or other similarly sophisticated natural depictions. In almost every painting, in the same way, one can just make out the round shape of what could just as well be a plate full of still-born infants as a circular fan. If we were to locate the “extreme” nature in Zhu Yu’s works here, it might be in his extreme knack for keeping up with the times. But even here, he will often carry a popular mode of expression to which he has adapted to its own extreme. Viewers can see this as they follow the trajectory of Zhu Yu’s thought in his practice. His works have been ordered in this exhibition—arranged in sequence based on when they were made.

Audiences shocked by Zhu Yu’s practices and “incidents” during the early years may gasp at the present display of elegant images. The rebellious edge is gone, the “Golden Age” of performance art in China has perhaps hastily wound to a close, and even that “Age of Idealism”—so romanticized—is nowhere to be found. But if we stop and consider for a moment everything that went on in those years, are hopes of Zhu Yu’s continued persistence towards extremes themselves justified? Over twenty years ago in mainland China, the radical art that began to appear was more like a series of decontextualized performances floating amidst the blind conformity of the post-colonial age and the continuation of pre-Enlightenment collectivist thinking. It may also be said that the use of radical or extreme approaches for the sake of symbolic resistance to power is tantamount to an incorrect choice of weapon. In the ongoing discussion about the construction of the body in culture brought on by “Foucault fever,” the body has been imagined by some artists as a kind of signifier. But as to what is being signified, nothing has been clearly articulated. In essence, this is no different from the “armed struggles” of the Cultural Revolution: weapons are in hand, but an enemy has not yet been determined. So when it comes to the past and present for Zhu Yu and the rest, the truly meaningful question is: who has encouraged them? Who has changed them?