Another work that found good advantage in this setting was Hai Bo’s photographic diptych “2008-1.” Presenting the image of an elderly man from the front, apparently in motion walking towards the viewer, and from the back, appearing to walk away, “2008-1″ is one of the most enduring “double portraits” from the artist’s recent work that build on the comparative approach between “then” and “now” that won Hai Bo deserved acclaim in the late 1990s. The light is perfect, the mood poignantly nuanced. Although recognisably elderly in years, the figure is nondescript—working class probably, but retired and therefore dressed in the generic simplicity adopted by those of his generation, except for the contemplative aura in which he is deeply immersed. The intensity of his inward-looking gaze is compelling, and somehow renders him so utterly, comfortably alone such that we are drawn into the aura of the work utterly ourselves, and into our own zone of introspection, fuelled by far less a measure of comfort than what Hai Bo’s subject enjoys.

A similarly mesmerising aura pervades Li Songsong’s “Big Container.” This new work—one of only a few from recent years in the show—is a pale, slumbering mass. The surface formed precisely of a final fat coat of pure paint, similar to Li’s paintings, to achieve a form that is a striking embodiment of pure power: its elegantly champfered sides might suggest the lower section of an elongated pyramid should the work be presented outside of China; yet, in being shown here in Beijing, whispered, instead, the language of the monumental associated with ideology and its icons. Was it this inalienable quality and the inevitable readings of the work being anticipated that led to its placement in one corner of the gallery space? For sure, the semi-umbra of the site enhanced the work’s present but did leave it hanging in the dark. This, for me at least, was the first hint of the problems of reconciling powerful and radical experimental art forms with the material efficiency demanded of collectable art and, of necessity, by its purveyors.

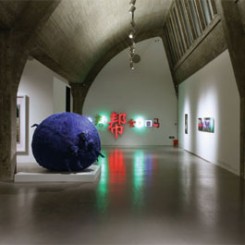

Conversely, He An’s installation “Do You Think that You Can Help Her, Brother?” was both beautifully placed and beautifully installed, but as a result of this failure to reconcile the extremes, the work felt emasculated, its decorative aspects overwhelming its original intent. “Do You Think that You Can Help Her, Brother?” comprises a set of individual characters each of which was acquired by illicit means from their original place within one form of public signage or another. In short, each word / character was removed at the behest of the artist in a clandestine fashion without the prior knowledge of their owners. So, on one level “Do You Think that You Can Help Her, Brother?” is intended as a radical statement on ownership: think “Property is theft,” the statement by the French anarchist Proudhon, compounded with “what’s yours is mine” (and that what’s mine is also mine…) in deep cohesion with (Western) materialist society today. In terms of both form and content the sentiment expressed further references the state of being alienated, excluded and disenfranchised that accompanies the experience of urban life for many young people in China today. Its inclusion in “Great Performances” reveals how far a work born of a gritty social realism can be transformed into a parody of itself, certainly a travesty of an artistic idea when co-opted by “the establishment.” A fitting analogy might be how the most worrisome emblems of punk circa 1977—safety pins, rips and tatters, skulls and crossbones as well as God Save the Queen sloganeering—latterly found their way into couture by luxury brands such as Chanel or Dior.